My Time Making ‘Shaft’ With John Singleton

When Shane Salerno co-wrote the Shaft remake with John Singleton, they started a friendship that lasted until the filmmaker’s untimely passing. Here he writes about his friend.

When John Singleton told you a joke, he would share it with you like it was a secret. When he delivered the punch line, he would lock on your eyes so he could study your reaction, just like a director watching a take on a monitor. If you didn’t laugh as hard as he hoped you would, he would tap you a few times on the arms or chest with his hand and repeat the punch line again to elicit the laugh he felt the joke deserved.

Related stories

Universal Film Chairman Donna Langley Cites Director John Singleton For USC Grads

John was a dedicated reader and a voracious consumer of films, TV shows, games, books, comic books, and graphic novels. If it had a good story and images, John would buy it, watch it, play it, or read it. His living room looked like a crime scene of entertainment.

John loved movies. Every filmmaker should love movies. (Some don’t, but that’s another story.) But more than just loving movies, John rooted for movies. He wanted every movie to be good. I never once saw John exhibit jealousy toward any film or filmmaker. He wanted you to be your best as an artist, because that would result in the best movie, which was all that mattered to him.

John loved the water. He kayaked in Marina Del Rey most mornings and sailed his boat “J’s Dream” up and down the Pacific Coast, sometimes dancing on the deck with his children. At the time of his passing, his Twitter bio didn’t list his many accomplishments. It didn’t say “Director of Boyz n the Hood” or “Executive Producer of Snowfall.” It read simply: “John Singleton: Always on the water.” For John, it was the happiest place on earth.

John had an encyclopedic knowledge of film. If he loved a film, he would go back and watch everything that particular filmmaker ever made and explain to you in microscopic detail how the work had developed and evolved – whether you wanted to hear it or not, and especially if you had writing to do or it was late at night and you just wanted to go to sleep.

John was really all about family. The making, breaking, and reconciliation of families echo through his films. John got his focus and strength from his mother Shelia and his expansive (and sometimes wild) imagination and playfulness from his father Danny. At USC, John was a driven and award-winning film student who was obsessed with making it as a writer-director in Hollywood. If you had the keys to an ambition factory in 1989, you would have built John Singleton.

“I recommend film school to get the fundamentals, but I recommend life to learn how to make a good film,” John said. And it was his own life that he drew on when he wrote the screenplay that would change his life. Every filmmaker starts somewhere, but John’s first film was the classic Boyz n the Hood. It came out in 1991, the year I graduated high school, and it’s impossible to explain to anyone who wasn’t around at the time the impact that film had on the culture. John showed the world what was really going on in the streets of Los Angeles and in many cities across the country. He educated and entertained. The film turned John Singleton from a very recent USC college graduate into a major filmmaker and was transformative for a nation and a generation of filmmakers.

Boyz n the Hood was a major critical and commercial success. It received a twenty-minute standing ovation when it was screened at the Cannes Film Festival. It was nominated for Best Director and Best Original Screenplay at the 64th Academy Awards, making John, at 24 years old, the youngest person ever nominated for Best Director and also the first African-American to be nominated for the award.

John Singleton had arrived. A big, bold and fearless new voice clad in a Malcolm X T-shirt and a baseball hat that read “South Central Cinema.” Sidney Poitier and Barbara Streisand sponsored his Director’s Guild application. John visited Francis Ford Coppola on the set of Dracula and Steven Spielberg on the set of Hook. Coppola told him to “write as many films as you can, keep them personal, and make films you’re passionate about.” His childhood cinematic heroes were now his friends. He testified before Congress in July 1992 and warned that the failure to combat the hopelessness felt by children living in the inner city would result in catastrophic loss of life, record drug use, and mass incarceration. In 2019, we’re living the nightmare that John Singleton tried to warn us about.

John used his new influence to inspire and encourage an army of gifted black actors, writers, directors, and producers to follow him through the hole in the wall that he (and the pioneering black artists before him) had helped to knock down. John supported artists of all races, he pushed for diversity, and using his hero Spike Lee’s example he hired, promoted, and advocated for people of color in film, television, books, comic books, and journalism. As John said, “If there are more black filmmakers, then hopefully they’ll be more Mexican American filmmakers, Asian American filmmakers, and Native American filmmakers documenting what’s going on with their culture.”

Following the success of Boyz n the Hood, John made his professional home at Columbia Pictures, sticking with the studio and executives (Stephanie Allain and Frank Price) who had backed his film debut. John made three films for the studio in five years: Boyz n the Hood, Poetic Justice, and Higher Learning. The match that was struck by John in Higher Learning in 1995 burns brightly on the evening news today.

Boyz n the Hood created the wave, but Higher Learning was ahead of it.

When many wanted a quick clone of Boyz n the Hood for his second film, John bravely took audiences in the opposite direction and delivered Poetic Justice, a female-centered love story and road picture with poems by Maya Angelou and strong performances from Janet Jackson and Tupac Shakur. When Poetic Justice (which debuted at #1 ahead of In the Line of Fire) and Higher Learning (which debuted at #2 just behind Legends of the Fall) didn’t live up to Columbia’s box office expectations, though both were profitable films for the studio, many filmmakers would have felt intense pressure to play it safe and produce a mainstream hit.

Not John Singleton.

In 1997, with dozens of commercial films being offered to him, John used his influence to make Rosewood at Warner Brothers. Rosewood is a searing racial drama, based on real life events – it depicts a white lynch mob attacking the black residents of Rosewood, Florida. It won widespread critical acclaim, but the marketing was badly mishandled – the film was dropped in February instead of being properly released in December – and the result was a disappointment at the box office. The heat that had powered five years of powerful and groundbreaking cinema had momentarily cooled.

And that’s when I met John Singleton.

In 1997, I was 24 years old and John was 30. I had just finished co-writing Armageddon for Michael Bay and Jerry Bruckheimer. The film was still a year from being released when Scott Rudin called to tell me that John Singleton wanted to meet with me to discuss co-writing a remake of Shaft with him at Paramount. The only thing they told me about the new film, then titled Shaft Returns, was that John Shaft would be a NYPD detective and not the famous private investigator from the original classic film. I knew a lot about cops. I had apprenticed on NYPD Blue during their first season and written for New York Undercover, but I had only written four film scripts: a production rewrite of the film Breakdown directed by Jonathan Mostow, a World War II submarine movie for Steven Spielberg and the newly formed Dreamworks, a spec script that had sold earlier in the year, and Armageddon. John could have had any writer he wanted, but for some reason he wanted me.

1997 was an interesting time to come into John’s life. He had been on a bullet train racing through Hollywood since he graduated from college. He had become a household name filmmaker, directed three films and a massive music video with Michael Jackson, Eddie Murphy, and Magic Johnson, inspired millions, and been celebrated all over the world. But when Rosewood didn’t perform, John saw the flipside of Hollywood. He witnessed scared executives and producers who now felt they needed to “help” John, the polite code word for “control” John.

During our meeting, I found a moment to mention to John that I was white. John rolled his eyes and nodded (a signature for him during any conversation) and then he said “I’m interested in your writing, not the color of your skin.” He also reminded me that Shaft was created by a white guy named Ernest Tidyman, the screenwriter and novelist who won an Oscar for writing The French Connection.

John and I took a walk around the Paramount lot to discuss working together. At that time, John was part filmmaker and part rock star. Everyone wanted to stop and talk to him, shake his hand, get his autograph, or pepper him with questions. John explained how much Shaft had meant to him growing up. As a kid, he wanted to look and dress like Richard Roundtree, take no shit, and be that cool. Years later, his Twitter and email address would all be variations of Shaft6816.

We bonded as we talked about our shared love of Star Wars, The Godfather I and II, Blade Runner, James Cameron, Spike Lee, Scorsese, Michael Mann, Francis Ford Coppola, George Lucas, Chaplin’s The Great Dictator and Kurosawa. When I talked about my love for Steve McQueen, John snapped back immediately that Shaft was the black Steve McQueen. He could talk Fellini and Almodóvar in the same detail as he talked about Spike and Scorsese. He was a real Star Wars fan, the kind who knew the most obscure details and enjoyed recounting them as he blasted the John Williams soundtrack in his car.

After Rosewood, John had somehow gotten a reputation for being difficult to work with. It prevented him from being offered certain projects, and it followed him, unfairly, for the rest of his life. On Friday, April 5, 2019, just a few weeks before he passed, John sat down for an interview with The Hollywood Reporter. He confronted the reputation issue head on, saying: “Part of my reputation that I don’t like is that I’m some, like, black militant guy, really serious and I don’t like white people.”

To set the record straight, nothing could be further from the truth.

Ask anyone who really knew John what he was like and one of the first things they will tell you is that John had a huge heart. In the twenty-two years that I knew John, he was always a sweet, generous, and very funny man. He could be really goofy, too. And you can’t be as goofy as John could be (John did the Urkel dance better than Steve Urkel) and “militant” at the same time. To the people who spread that crap about John, know that it hurt a good man, and that’s on you.

For Shaft, John wanted Will Smith and Lauryn Hill for the two leads. Will had become a massive star following Bad Boys and Independence Day, and Lauryn Hill had just won six Grammys. John sketched out the movie poster and played the Oscar-winning Isaac Hayes theme song so loud for me in his car that the bass shook the windows of the buildings surrounding the parking lot. John talked about his hero Gordon Parks, Richard Roundtree’s infamous walk (John’s father Danny told John playfully when he was a kid that someone must have seen his dad walking and created Shaft right then and there), what the film meant, especially to black men, and the responsibility we had to make it good and to get it right. I was hooked. I was sold. I said yes.

On one of our first research trips for Shaft, we ended up waiting in the terminal at LAX for our flight to New York. Mark Wahlberg walked toward the gate. He was on the same flight. He knew John, said hello, and they started talking. Then Lawrence Fishburne walked up, hugged John, and joined the conversation. Same flight. Then Robert Towne (one of John’s all-time favorite screenwriters). Also on the same flight. This was pre 9/11, so after we were in the air the stewardesses let the four of them stand in First Class and just talk movies and share war stories for five uninterrupted hours. I’m proud of the fact that at 24 I was smart enough to just sit there and listen. It was like the world’s coolest film and culture podcast playing out live in front of me.

As we were getting off the plane, Wahlberg and Singleton made a promise to work together someday. That partnership happened in 2005 with Four Brothers, which debuted at #1. And then Towne grabbed his bag, turned, and invited John and me to see his latest film, which he had come to New York to screen. It was called Without Limits and told the story of Steve Prefontaine, one of the world’s greatest runners. The film featured amazing performances by Billy Crudup and Donald Sutherland and was shot by the legendary Conrad Hall. After the screening, Towne took John and me out to dinner. Drinks. Food. Cigars. They talked for hours. Story after story. Bonnie and Clyde, The Godfather, Chinatown, The Last Detail, Shampoo, The Firm, Mission Impossible. Again, I just sat there, listened, and learned. Without Limits had a big impact on me. When I got home, I bought a golden retriever and named him Pre.

When we were writing Shaft, we would often get into cabs in New York, and anytime there was a black cab driver, and they would see that it was John in the rearview mirror, they would turn around and say some version of: “Hey, John, I’m a big fan. I loved Boyz n the Hood. I heard you’re going to make Shaft. Listen, John, don’t f*ck up Shaft.” John would nod. He understood the warning, and he would always look over at me to make sure I understood it, too.

Late one night, John kept trying to hail down a cab. Cab drivers in New York had a nasty racist habit of not picking up black men, especially late at night. Empty cab after cab passed John without pulling over. John had an elegant way of having his hand seamlessly switch from hailing down the cab to flipping off the passing cab driver. He was would flip off each passing cab with greater finger emphasis.

When John took me to white clubs in Los Angeles or New York, there would be no police there. When John took me to black clubs, there would be cops everywhere and often hassling people for no reason at all except that they were black. John explained racism to me in a way I had not fully understood before. He explained “quiet racism” to me and how day-to-day discrimination by people in power was the worst kind of racism of all.

One day, I showed up for a story meeting with Scott Rudin in New York, without John. Scott was upset. He yelled at me. A lot. He told me to call John. I did. No answer. I kept trying. No answer. Finally, John walked into the meeting with a bag of food and the biggest smile I’d ever seen.

Scott: “John, you’re two hours late, what the hell is going on?”

John: “It’s the Puerto Rican day parade. Finest women from all over the city are in the streets dancing and looking fine as hell. What was I doing? I was getting numbers.” (Meaning phone numbers). Scott looked at John for what I swear felt like a year. And then he opened the script and started to give his page notes. Having been in this business for twenty-seven years, trust me when I tell you that only John Singleton could have given that answer to Scott Rudin and gotten away with it.

John brought me to a lot of events and premieres. Going out was not really my thing, but John liked to go out most nights and he was very generous about bringing me along and introducing me to actors, directors, producers, and music and sports stars. On December 14, 1997, John called me and told me we were going to the Titanic premiere at Mann’s Chinese Theatre. We met as we always did out front (on Hollywood Boulevard) and started to walk in. It was only then that John revealed to me that we did not have tickets. “What do you mean we don’t have tickets?” We always had tickets, because John always had the hookup. But not tonight.

Worried, I said, “How are we going to get in without tickets?” He just looked at me, shook his head, and said, “Trust me.” He blew right past the first usher with a wink and a wave. He got past the second usher with a focused stare and some kind of Baldwin Hills Jedi mind trick and suddenly we were inside. Everyone in town was there, huge celebrities and all of the industry heavyweights, many expecting to see the “disaster” the press had promised for a year. Everywhere I looked, there was a major star. But we still didn’t have tickets.

The lights started to flicker on and off. It was time to take our seats. Except we didn’t have seats because we didn’t have tickets and we weren’t supposed to be there. There were two unfilled seats next to Army Archerd and his wife, but they were marked ARMY ARCHERD and I was sure their guests would arrive any minute.

At the last minute, Archerd got up and walked into the lobby. He came back and sat down again. And then this usher – who clearly was a huge fan of John’s – walked up to us with this huge smile on his face. “Mr. Singleton, we found your tickets.” John took them, thanked him, and smiled at me. We took our seats. Left center, row 25, seats 111 and 112. The theater went dark. The movie started. The logos were rolling and John looked over at me. “I told you to trust me.” I shook my head in disbelief and the two of us sat in the dark for three hours with a few hundred other people watching what would soon become the highest-grossing film of all time.

I still have both of our tickets from that night.

Fifteen years later, James Cameron asked me to co-write the four sequels to Avatar, which had overtaken Titanic as the highest grossing film of all time. When my hiring was announced on Deadline, the first call I got congratulating me was from John. He was laughing. He was so proud. He said, “You gotta tell Cameron how we saw Titanic!”

When I said earlier that John rooted for films, I should have added that he also rooted for and championed artists. When John believed in you, he fought for you and never wavered. He also had a spooky eye for talent, casting a number of major stars long before they were Oscar, Emmy or Golden Globe winning or nominated actors or movie stars, including Angela Bassett, Cuba Gooding, Jr., Ice Cube, Regina King, Taraji P. Henson, Tyrese, Jennifer Connelly, Ving Rhames, Don Cheadle, Jada Pinkett Smith, Dave Chappelle, LL Cool J, Eva Mendes, Chiwetel Ejiofor, Terence Howard, Garrett Hedlund, Zoe Saldana, and many others. It’s a testimony to John that many of the actors on this list worked with him three, four, or even five times.

When Jordan Peele won the Oscar for Get Out, John was thrilled. Sitting at the bar backstage at the Oscars, John told a reporter at Variety “Black presence in the film industry is finally catching up to the music industry, and that makes me feel like America is more American.” John was equally happy when Regina King, Ruth Carter, and Hannah Beachler all won their Oscars, and especially thrilled when his friend and hero Spike Lee won his first Oscar for Best Adapted Screenplay. John loved Spike Lee and always spoke fondly of him. “When I was 18, I saw She’s Gotta Have It. The movie was so powerful to me, as a young black teen who grew up seeing movies with not a lot of people who looked like me.”

John pitched me Black Panther twenty years before it became a billion-dollar franchise, complaining to me two decades earlier that there wasn’t a black superhero and that the black audience would come out in droves to be properly represented. He was right. He wanted to make a film of Marvel’s Luke Cage for many years. I wish Columbia had supported his vision and made the film. There is no doubt it my mind that it would have been a major success.

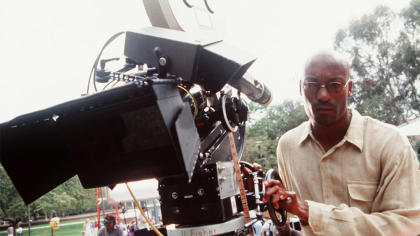

John had a special place in his heart for Steven Spielberg, too, and often credited Steven for helping him become a filmmaker. “Happy birthday Steven Spielberg,” John wrote in December 2018. “One of the greatest filmmakers of all time and an all-around honorable guy. I’ve learned so much from this man’s journey as a storyteller…one of the things I’ve learned from watching his work is how to evoke an emotional response from an audience – fear, suspense, excitement, and most importantly love. Thanks Steven.” John took me to the premiere of Amistad (the photo of us was taken at that premiere) and when John and Steven talked afterward it was like seeing a kid talking to his favorite sports hero. John really loved Steven. He loved George Lucas, as well. He was in awe of the imagination that had birthed Star Wars.

John never lost sight of his roots. He didn’t live in Brentwood or Beverly Hills or Santa Monica or Pacific Palisades. He lived in Baldwin Hills, on a regular street populated by people who didn’t work in the film industry. This was important to John.

As John said, “I’m a director, but I’m also a teacher. I’m a lover of cinema, and I love working with people who are hungry and have the energy to really do better work.” John’s issue was always about keeping it real and he fought against anything that even danced on the dental-floss thin line between real and fake.

John said that one of the best lessons he learned about managing the ups and downs of Hollywood came from going sailing. “You’re at the mercy of the elements,” he said. “You’re close to God. It’s the same as directing… in that there’s a certain amount that you have that’s in your control and there’s a lot of a certain amount that’s not in your control, but you’re able to guide and navigate the whole thing.”

Shaft came together with a tremendous cast including Samuel L. Jackson, Christian Bale, Jeffrey Wright, Toni Collette, and Busta Rhymes, but it was a tough shoot. The producer and director didn’t get along. The producer and star had real differences of opinion. Post-production was brutal. The movie changed, evolved, bent, broke, and finally came together at the last minute.

When Shaft was released in 2000 against tough competition (Mission: Impossible II, Gone in Sixty Seconds), it debuted at #1. This meant a great deal to John. He called me. He was so happy to have a hit film. Shaft received largely positive reviews and reminded a lot of people how gifted John was. But after the difficult process of filming Shaft, John insisted and obtained final cut for his next film, Baby Boy. It is a film that was tremendously important to him.

John followed Baby Boy with 2 Fast 2 Furious, the sequel to The Fast and the Furious. 2 Fast 2 Furious earned $50,472,480 in its opening weekend and was John’s third #1 film at the box office. The film became, at that time, the highest grossing film by a black director. John had made history once again.

In 2002, the United States Library of Congress selected Boyz n the Hood for preservation in the National Film Registry and called it “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant.” And on August 26, 2003, John received his star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, with his parents and children in attendance.

John returned to Paramount Pictures and directed Four Brothers in 2005, the fourth film in his career to debut at #1. That same year, John shook up the business again by taking out a mortgage on his house to finance and produce Hustle & Flow. The film hit the 2005 Sundance Film Festival and was the subject of an intense bidding war.

The studios that were chasing the film had rejected it when John was initially pursuing funding. John closed a major $9 million deal. John told Peter Bart that he felt “vindicated.” Hustle & Flow came out of nowhere and was a solid success, grossing many times its $4 million budget, launching several careers, and once again demonstrating John’s remarkable ability to connect with an audience.

After the Sundance deal was announced, I sent John an email congratulating him. He wrote back: “Thanks man. I’m trying to make big things happen.” John dreamed of making a series of low-budget films like Boyz n the Hood and Hustle & Flow. Unfortunately, that dream didn’t happen.

In the fourteen years that followed, John directed only one more feature film. “Honestly speaking, I was bored with the whole industry,” John told a journalist a few years ago. “I was spending time on my boat in the marina, sailing up and down the coast. I became kind of an ocean vagabond – just reading and writing. I was disillusioned.” In another interview he explained the hiatus this way: “Raising my kids, sailing – learning how to sail and just like, living life. There’s a lot more life outside of movies.”

John came back to directing via an episode of Empire. As John explained to an interviewer,

“It changed because Lee Daniels asked me to direct Empire. And it was re-energizing. I was like, I could do this. I could create something. And I started writing.”

Bolstered by the reception to his work on Empire, John moved into groundbreaking television, directing acclaimed episodes of FX’s The People vs. O.J. Simpson, Snowfall and American Crime Story as well as Rebel and Billions.

I was blessed to visit John in the hospital shortly before he left us. It broke my heart. I kneeled, grabbed his arm, prayed for him, and thanked him for believing in me at the beginning of my career, when it really mattered most.

When I looked at John for the last time, I heard his voice in my head, something he had written once about sailing a few years ago:

“It’s a whole other thing to be on the water in God’s creation and enjoy his magnificence. I’ve been in some truly intimidating weather exploring up and down the Pacific coast and the one thing I can say it has brought me closer to God. I’m not scared or fearful when I’m in these situations because I know he’s got my back… Something that few of us can say even when on land.”

When asked what his greatest achievement in the film business was, John told one interviewer, “My greatest achievement is I’ve been in this business for over 26 years and I haven’t lost my soul. There’s a whole lot of people who are very, very successful and they don’t even know which way is up anymore. Right? And I feel really cool that I’ve had my highs and my lows and I’m happy. I don’t have any of that, ‘Damn, should I have done this?’ I don’t have any of that bile, you know what I mean?”

His death at 51 stunned Hollywood and the world. On Monday, April 29, 2019, we lost a trailblazer, a history maker, a proud, strong, generous, and charismatic five-foot-six giant.

I always thought Boyz n The Hood was the best film John ever made.

Until I attended his funeral.

And it was then that I realized that John’s seven children – Justice, Maasai, Hadara, Cleopatra, Selenesol, Isis, Seven – were John Singleton’s real masterpiece.

“Condolences to the family of John Singleton,” President Barack Obama wrote. “His seminal work, Boyz n the Hood, remains one of the most searing, loving portrayals of the challenges facing inner-city youth. He opened doors for filmmakers of color to tell powerful stories that have been too often ignored.”

There will be many tributes to John in the days, weeks, months, and years ahead. And deservedly so. He helped a lot of people and directly inspired so many major artists, including Ryan Coogler, Barry Jenkins, Ava DuVernay, Jordan Peele, Geoffrey Fletcher, Steve McQueen, Ice Cube, F. Gary Grey, Peter Ramsey, Tyler Perry and so many others. There were people who knew John longer than me and better than me. But he was my friend for twenty-two years and I was blessed to spend time with the coolest film geek in town. I will always think fondly of those times and all the great laughs we shared. Thank you, John. For everything.

John Singleton was here.

John Singleton mattered.

John Singleton will never be forgotten.

John, I hope you’re okay, and I hope wherever you are there is an ocean and your boat, and films and books and music and lots of comic books and happiness.

I hope the only thing louder than the waves will be the sound of your own laughter.

I wish you every good thing brother.

Stay forever cool, John Daniel Singleton Shaft.

Sign up for Deadline's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.