‘The Three Mothers’ honors women who raised Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X, James Baldwin

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

This story was published in partnership with The 19th, a nonprofit, nonpartisan newsroom reporting on gender, politics and policy.

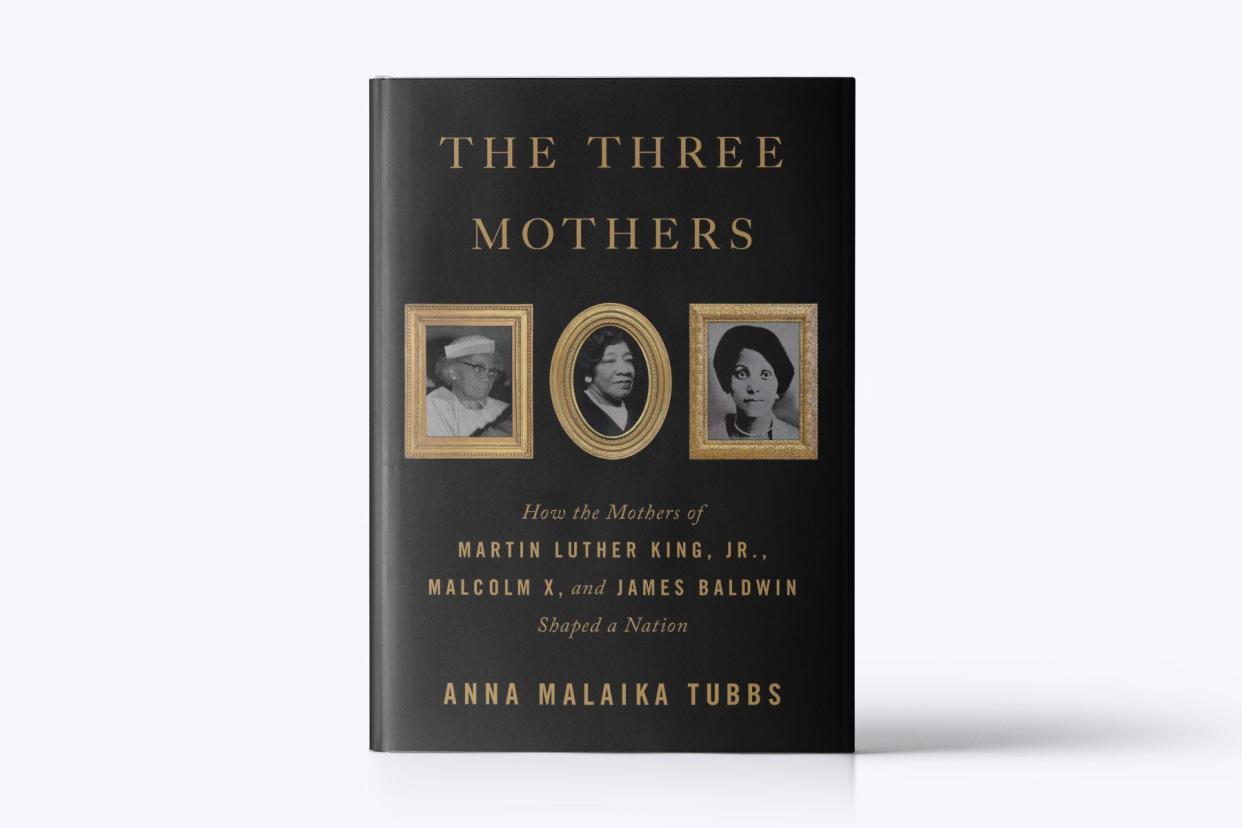

Before the world came to know three revolutionary men, they were sons whose mothers’ deep, honest love prepared each for lives of activism. Anna Malaika Tubbs’ biography, “The Three Mothers: How the Mothers of Martin Luther King, Jr., Malcolm X and James Baldwin Shaped a Nation” honors the women who reared some of the most famous men in history, but were subsequently all but erased from their legacies.

Tubbs, a doctoral candidate in sociology at the University of Cambridge, encompasses the lives of Alberta King, Louise Little and Berdis Baldwin. The mothers’ lives span from the 1890s to the late 1990s, through two world wars, the Great Depression, the Great Migration, the Harlem Renaissance, the women’s suffrage movement, the Civil Rights Movement and the deaths — in two cases, assassinations — of their sons. Although Tubbs highlights how these women instilled the lessons their sons ultimately shared with the world, she also illustrates that their lives did not begin when they gave birth.

By law, Alberta King had to give up her career as a public school teacher when she got married but she continued to teach through the church and her role as a mother. Alberta, who lived in constant worry for her son’s safety, was assassinated in 1974, six years after her son, in a shooting at Atlanta’s Ebenezer Baptist Church — the church her family built.

Louise Little, an immigrant from the island of Grenada, was a leader in Marcus Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association. After the death of Little’s husband, the single, landowning woman was in a Michigan state mental hospital for 25 years under dubious circumstances, scattering her children into foster care. Malcolm X was only reunited with his mother in the year before he was assassinated. He later said he had to block out the thought of her, feeling helpless and missing her wisdom.

Berdis Baldwin was a single mother when she had James Baldwin — her first of nine children. She married an abusive man who was diagnosed with mental illness near the end of his life. Berdis Baldwin acted as a buffer between her husband’s rage, and continued to instill the importance of education and freedom into her children. She lived to be nearly 100 years old.

“These men became symbols of resistance by following their mothers’ leads,” Tubbs writes.

Tubbs became a mother herself in the process of writing and researching this book. “We didn’t know the sex at the time, we left it a surprise,” she said in an interview. “But, as I was writing, I was like it’ll be really funny if this is a boy.” It was. Tubbs’ husband, Michael, has been in politics for nearly a decade, most recently as the mayor of Stockton, California. Already, people have credited their son for being strong like his dad, following in his footsteps. In personal reflections throughout the book, Tubbs stresses that the biography is not about her, and also cannot ignore the personal connection to being erased from her son’s life in real time.

It does a disservice to everyone, including children, when we don’t share and honor Black women’s full life stories, Tubbs said.

“I think it’s one of the reasons these three men, Martin Luther King, James Baldwin, Malcolm X had such a beautiful understanding of the human condition: Their mothers were so honest with them about their own humanity,” Tubbs said. “I want more Black women to do that today.”

The biography, out now, does not shy away from recent events. The introduction opens with George Floyd’s last words: “I can’t breathe. Mama, I love you. Tell the kids I love them. I’m dead.” Tubbs wanted to remind readers that many of the ills the women at the center of this book raised their sons to keep fighting are still embedded in our society. One of the things that binds them together is a persistent worry for their sons, not only when they were in America’s spotlight, but as Black boys growing up in Jim Crow’s America.

In an interview with The 19th, Tubbs discussed the process of piecing together lives erased from history and the lessons we can take from the mothers’ legacies into our current world.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Question: I’m wondering how you first decided these three women would be the arc of your book.

Anna Malaika Tubbs: It was, at first, a hard decision, because when I started my Ph.D., all I knew was I wanted to join other scholars who were correcting the erasure of Black women. After “Hidden Figures,” Margot Lee Shetterly’s book and obviously the success of this film, but also Isabel Wilkerson speaking to the experiences of the Great Migration (in “The Warmth of Other Suns”), I knew I wanted to join those scholars. So that left this broad, broad, broad topic that I needed to narrow down. I knew that I had a limit: three years to complete my Ph.D. at Cambridge.

I realized I could start with famous men — that could be my hook. I started with Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X because everybody is always putting those two — incorrectly — as polar opposites. But I’d also recently watched “I Am Not Your Negro,” based on James Baldwin’s writing, and how he speaks about being a witness to his friends’ works. I felt like he was a natural third to go in a conversation with them, even though not everybody puts those three together.

I became really interested in the notion of the woman before the man, versus the woman behind the man — which, I hate that saying. I looked into their stories that I could find online at the superficial level. I wanted to push myself and challenge myself.

The fact that they were contemporaries, that they were all born within six years of each other and then their sons, the famous sons, all born within five years of each other gave me some really cool intersections. I could also comment on the sociological aspect of historical events and how they were playing out differently in each of their lives.

Q: All of your chapters open with at least two quotes. Some are from famous Black writers and commentators paired with some nasty quotes from white women of the suffrage movement. Could talk a little bit about including this?

Tubbs: Thanks for picking up on that. I was trying to be kind of clever with these quotes before the chapters, because each quote has to do with this decade of the mothers’ lives. A big part of the book is talking about the balance between dehumanization and us humanizing ourselves. It’s important to me also to address any kind of historic amnesia. This is not new, these sentiments are not new. People need to not be shocked about the riots, white supremacists do these things, they have always seen it this way we have so many accounts of progress on behalf of communities of color being responded to with attacks and violence and rage. That was part of what I was doing with the quotes as well.

I don’t want white women to forget: This is the history of what you all have said about us. And we can change that. But the only way we’re going to change that is if we acknowledge how many systems in our country are built on those beliefs that we were less than human, that we didn’t deserve the right to vote. And if we don’t understand that balance of us fighting against all these different forms of dehumanization, then we can’t appreciate how far we’ve come today.

Q: There’s a dichotomy you’re balancing in the book between these three mothers giving life to three prolific men while also constantly worrying about the fragility of their own lives and that of their sons. We have more words now in the public vernacular about maternal mortality and how it impacts Black women in particular. Can you say more about the role of mortality in the book? Especially because Berdis Baldwin’s own mother died while having her.

Tubbs: This part is so emotional. It’s so painful to be a Black woman in America, to have all of our loved ones be deemed as less than human, be treated as less than a human, and ourselves being treated this way, not being seen, not being celebrated. Quite often the only times we’re celebrated is when somebody is lost in our lives and we’re honoring our strength that we’ve persisted beyond losing them.

I do think though that the book comes out at a time when I couldn’t have planned a better time for it. We have Vice President Kamala Harris talking about Black maternal mortality in a way that hasn’t been spoken about at that level before, and it’s been erased, ignored. I’m excited to see what she’s able to do to address it. It’s evidence of the change that’s happening in our country.

More people are speaking about Stacey Abrams and other Black female organizers in Georgia. For me, I feel really honored to kind of join the conversation at a time where I have to do less convincing about the role of Black women, and I get to do more adding to the anthology of evidence of how much we’ve done to shape this nation. And now that we’ve proven it, can you please start listening to us so we can stop losing our loved ones?

Q: I learned more about the history of Ebenezer Baptist Church in your book, and how pivotal it was to Alberta King’s family, especially relevant now that Raphael Warnock won his Georgia Senate seat, and he’s the current pastor there.

Tubbs: It’s been really annoying, because those who have talked about Ebenezer only are speaking about Martin Luther King Jr. and his dad being reverends there. And it’s like, no, expand the history. This is Alberta’s church, her parents’ church and what they wanted to accomplish. Living through the Atlanta Race Riots in 1906, seeing that with her own eyes and now we have the pastor of that church as a senator is just a full circle moment.

Q: I have specific questions about all three women, but I’ll continue with Alberta King. We were just saying how she’s the daughter of Ebenezer Baptist Church, later known affectionately as “Mama King.” You also illustrate the losses she experienced throughout her life: Her parents at a pretty young age, her two sons within 15 months of each other, and then of her own life in a shooting at Ebenezer. Can you talk about her legacy of bettering the people around her and also the premonitory-like sense of how fragile Martin Luther King Jr.’s life was?

Tubbs: Alberta King, for me, what is most inspiring is how clearly her family could not have done anything that they did without her, her experiences and her background, her parents forming (Ebenezer) and then being so invested in their daughter’s education.

There was a recent movie that came out, “King in the Wilderness,” and they talk about how Rev. Martin Luther King, Sr., was this patriarch. That’s not true — even in his book he credits his wife with everything. His own biography is a love letter to his wife. When he met her, he was considered illiterate. She is this college educated, brilliant daughter of Ebenezer Baptist Church, and she pushes him and says, “Yeah, that’s great. You seem nice and all, but you need to get a degree, you need to be educated in order for our family to be able to do well.” She must have tutored him at least. How do you go from having an illiterate status to graduating from Morehouse? It’s because of Alberta’s father that he even gets into Morehouse. We need to credit her with every single one of these moments.

I think about the letters (Martin Luther King, Jr.) sends back and forth to his mom. It’s very clear he has a rapport with her that he doesn’t have with his father. His father speaks about that in his book, that Alberta has an understanding of her children that was so deep and her kids always corresponded with her. That’s how he got updates. It’s such a travesty to not understand how much she contributed to his journey, and the fact that we’ve for so long spoken about his father as his primary influence is really a crime.

Q: Berdis Baldwin raised James Baldwin as a single mother initially, and eventually had nine children with a mentally ill and abusive husband. She was also a writer and creative herself. Can you talk about this family?

Tubbs: There is a direct connection between what James Baldwin accomplishes for the world and his mother’s talent. She was this writer, even to the point that notes that she’s sending to excuse absences, the principal would be like, these notes are so beautiful. It’s clear that’s where he gets his writing talent from.

And when you speak to the family members they all talk about her letters and how brilliant she was. It was clear, she just had a mind — that was what her son inherited.

One of the things that I love the most about their story is that when James Baldwin passed away, this grave is bought for both of them. She has eight other children, but he wanted her to be buried next to him. What that means about the interconnectedness of their life, the way that it is inextricable, that he credited his mom with everything. She accepted awards on his behalf, he dedicated poems to her, he wrote her letters constantly. When he was out of touch with her he felt unsettled. I’m not making a stretch when I say how important she was, it was just obvious. It was easy to find these examples of his connection to her.

Something that was upsetting to me is that so often if we know about James Baldwin, we know about his abusive stepfather. So even if they had a great father like MLK Jr. did, or they had a terrible father, we’re still talking about the father. Why? Why are we saying that they’re the ones that have the most influence on them, whether they’re present or not, terrible or not? That’s, again, a crime against the Black mother who was there, day in and day out, standing up for him making sure he could still go to see plays.

Q: There’s a story passed down about Louise Little standing down white supremacists who came to terrorize her family when her husband was away. She’s pregnant with Malcolm X at the time, and you write that it was in his blood to resist. Can you talk a little bit about her life as an immigrant to the U.S. who travels throughout the country as a civil rights activist, who remains this pillar even after the state of Michigan institutionalized her?

Tubbs: Her journey for me, perhaps out of the three, is the most shocking and almost the most emblematic of Black women’s experiences in the United States — how clearly she showcases what rights are taken away from us just because we’re Black women.

Representations of her death said she had gone crazy. And that is heartbreaking when we think about that. Even Spike Lee’s representation of her in his film “Malcolm X” is that his mom went crazy. We’re not going to talk about the fact that her husband was murdered? Then after, she’s not given the life insurance money. Welfare workers are invading her property, her privacy, which is a very common experience for women of color.

A white male doctor decides she’s “imagining” being discriminated against. Can you imagine being in her shoes? Twenty-five years of her life she was taken away from her kids, and her kids were taken away from her. It’s just like one tragedy after the other, but she again persists. Her grandkids who knew her and got to know her in her final years of life, who even in some ways got to know her better than Malcolm X did, were so inspired by her. She was this powerful, brilliant, still very with it woman, after all the terror that she’d been through.

Malcolm X recognized how important his mother was to him. Scholars in the past didn’t pay attention to it, they didn’t care. That’s what I find to be really angering. I think with the book, hopefully, you question why you didn’t know these things. And that’s what we question: Who was keeping this from us and why? And how do we make sure that stops happening?

Q: Because these women have been so erased, you write that it was hard to piece together parts of their legacy — they’re not living, you can’t interview them. At times, you imagine things they might’ve been thinking about to bridge gaps. You also wonder about protections the three mothers could have benefited from: grief counseling, universal income, universal preschool, gun restrictions. Could you talk about those different safety nets?

Tubbs: For me it goes back to that goal of what I wanted to accomplish with this book as a contemporary commentary on where we are today as a country. There’s so much left that we need to fix. We’re still just honoring Black women because of their losses and celebrating, "Oh, wow it’s incredible what they’re able to persist through, how cool, how strong they are,” as if we don’t feel pain. A big part of the Black maternal mortality crisis actually is this lack of understanding that Black women feel pain or that they know when they’re hurting or when something’s wrong.

That section for me is this Black feminist manifesto of what still needs to change. I’m sick and tired of us talking about how much we’ve made it through and how much we need to honor Black women for doing that. Let’s question why we’re still having to face those challenges. A lot of these things would not only benefit us, it would benefit our entire country. All women, all parents, would appreciate universal child care that’s quality, universal preschool so our kids can all start at the same time and be cared for. Even parental leave, and how differently that’s experienced in different countries, so you don’t have to sacrifice your own career or your own education.

Gun laws, we so often think about this as just numbers and data and statistics. But in three cases, gun laws could have saved them. I do hope that when we have human connections to these issues, when we’re carrying their stories in our hearts and realize how many Black mothers relate to their stories today, we can make more change. The three mothers’ lives would have been completely transformed by so many of these interventions.

Even when we talk about abolishing the police, if Berdis could have called someone who wasn’t a police officer to intervene with her abusive husband, she might have actually had a support system around her where she didn’t have to just take on that burden herself. And there are so many Black women facing domestic violence right now who do not feel safe to call a police officer to help them with their situation. The list goes on and on.

I think some people think that these issues are just so large and so embedded in our nation that they can’t be fixed, but the truth is there is a path forward. And there are very specific policies that we could address to make things easier for a Black women today.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: 'The Three Mothers' honors women who raised MLK, Malcolm X, Baldwin