Three Latin American Music Legends Protecting the Past To Secure the Future

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Ask your parents, grandparents, or any nearby elder, and they’ll tell you that though the world has changed since their youth, many of the fights have not. Debates over racism, LGTBQ rights, and gender inequality rage today as if they were brand-new — and that means ancestors and veterans of past struggles can often offer lessons for grappling with an uncertain future.

Perhaps that’s one reason why Latin America venerates its musical legends. Just look to social media’s obsession with Mexican balladeer Paquita la del Barrio, merengue típico meme queen Fefita La Grande, and Brazil’s recently departed samba icon Elza Soares. Diligent music fans have also re-engaged with the foundational legacies of rhythmic guardians such as Colombia’s Gaiteros de San Jacinto, and the groundbreaking pan-Caribbean fusions of Xiomara Fortuna.

More from Rolling Stone

Welcome to Diego Raposo's World of Daring, Demented Latin Pop

'Blue Beetle' Is the Same Old DCEU Superhero Movie - With One Big Difference

How the All-Women 'Mujeres Del Movimiento' Festival Broke Barriers

All of them have taught younger generations of fans to study the music they love and remember how great art can respond to any moment. Many living legends are still eager to share their hard-earned wisdom, and as the world plummets into algorithmic homogeny and impending climate calamity, we’d do well to listen up.

Rolling Stone spoke with three icons of Latin American roots music, looking over their influential, trailblazing careers and drafting a poignant map for the road ahead.

Luzmila Carpio: ‘We must mend our relationship to nature before it’s too late’

One of the most prominent Indigenous singers to emerge from Latin America — in the region also known by the pre-hispanic name of Abya Yala — is Luzmila Carpio, the Bolivian folk singer who throughout the 1970s and ’80s proved her dizzying whistle tone could shatter both glass and Western political structures. She was born in 1949 in the Quechua-Aymara community of Qala Qala, where she learned the stories of mythical heroes and songs of harvest. In tune with the primordial rhythms of nature, she learned to sing by imitating songbirds. But with age came awareness that not everyone was in step with the Earth’s heartbeat.

“When I arrived in the city and saw so much marginalization, I decided my mission would be to defend the identity of my Aymara-Quechua people,” she tells Rolling Stone, speaking from her home in La Paz. “In the beginning I recorded Quechua songs for parties and dancing, but I quickly realized I wanted to awaken pride for our roots. I felt a need to defend the rhythms of life, that which Mother Earth Pachamama has gifted to us. Political powers became worried by my message and that Indigenous values would proliferate. That’s why in the 1980s I headed to Europe, to show the world how valuable my Indigenous culture was.”

Carpio settled in Paris, becoming an essential mouthpiece for the plight of Indigenous people and a beacon of Andean music and culture on the global stage. She collaborated with a plethora of international musicians on nearly a dozen albums, and was even appointed as Bolivia’s ambassador to France in 2006. Nearly a decade later, a new generation discovered her evocative storytelling through the reissued Yayay Jap’ina Tapes, released by French label Almost Musique. This put her on the radar of U.S./Argentina folktronica label ZZK, which tapped its roster of electronic producers for an acclaimed 2015 remix album, bringing Carpio’s unique birdsongs back to the dance floor.

“It was a dream that young people would dance to my music with electronic rhythms,” she adds. “I am fascinated by the younger generations, and I think it’s vital they too reconnect with Pachamama. The title of my new album, Inti Watana – El Retorno del Sol, alludes to holding on to the sun and treasuring its many gifts. We must mend our relationship to nature before it’s too late.”

Inti Watana – El Retorno del Sol arrived during the September equinox via ZZK, and once again features the Andean drums and quenas of her past work, this time complemented by atmospheric synths and digital sequences produced by Leonardo Martinelli, a.k.a. Tremor. The album punctuates a series of collaborations that in recent years have deepened Carpio’s relationship with a younger crop of artists. She previously composed the song “Chillchi Parita” as the theme for the 2009 animated short Abuela Grillo, which responded to maligned water privatization efforts. And her 2017 crossover with Bolivian heavy metal band Alcoholika La Christo on “Warmikuna Yupay-Chasqapuni Kasunchik” was a thunderous call for women’s equality that symbolically passed her lifelong fights onto a new generation that must carry them into the future.

Polibio Mayorga: ‘Stop letting the dead speak for you!’

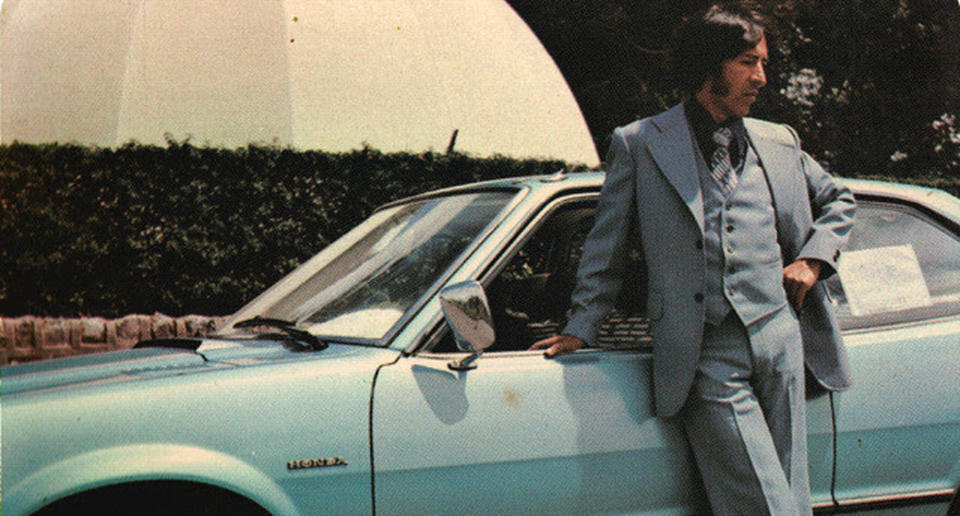

Legendary status is often awarded to artists seen as guardians of tradition, but in some cases a disruptive legacy of innovation does more to cement someone’s place in history. Ecuadorian composer and multi-instrumentalist Polibio Mayorga was mocked by his peers in the 1960s when, tired of performing Cuban son and Colombian cumbia standards, he decided to put a fresh Andean spin on tropical music. 1967’s accordion and requinto-arranged “Cumbia Triste” was registered as Ecuador’s first original cumbia and became an international smash reimagined in following decades by Colombian vallenato master Lizandro Meza and Mexican tropi-psych wizards Sonido Gallo Negro.

“I didn’t understand why we had to keep playing other people’s songs,” Mayorga says. “I’ve always been interested in what’s new, so I was the first one to bring the Moog, the Mellotron, and vocoder to Quito. I popularized the Hammond organ, and I composed many hit songs on the accordion. I never felt alone [as an innovator], but I also never kept the company of people who opposed my curiosity.”

Mayorga, who is now in his nineties, used cutting-edge technology to expand the vast compendium of Ecuadorian rhythms such as pasillo, yaraví, and sanjuanito. His experiments on the Moog synthesizer in the early 1970s made space-age hits out of “Ponchito de Colores” and “Bien Bailadito,” cementing him as one of the architects of techno-cumbia. His influential work is frequently cited by Ecuador’s current generation of indie artists, from genre-rebellious troubadours Lolabúm to ambient and club producer Quixosis. Earlier this year, German crate-digging label Analog Africa released a retrospective of Mayorga’s more exploratory electronic works, while a new album of original compositions titled Cumbia Pishcodélica is slated for release in the coming months via Musicoteca Ecuador.

“Over the years I’ve encountered many people who claim to be saving music, but their actions rarely go beyond words,” he reflects poignantly. “I urge young musicians to study and be original, to fully develop their ideas. Showcase your talent instead of recording other people’s songs. Stop letting the dead speak for you!”

Enerolisa Nuñez: ‘You learn this music from the elders’

In the case of the Dominican Republic’s Enerolisa Nuñez, it’s likely you’ve heard her songs of syncretic praise across popular music and just haven’t realized. Described as the queen of música de salve, the influential cantadora hails from the rural community of Mata Los Indios in Villa Mella, a district on the outskirts of Santo Domingo with an ancient and vibrant Afro-diasporic heritage. Handcrafted drums and tambourines called palos and panderos provide the percussive backbone for salve, pri-prí, and congo de Villa Mella, which themselves are the rhythmic roots of dembow and even merengue.

“You learn this music from the elders,” Enerolisa says, highlighting how música de salve is also mostly performed by women. “I learned because my mother and aunt sang with their panderos and they’d take me to [prayer ceremonies called] velaciones. I’ve been performing since I was eight, and now I have a salve group with my own family to keep these stories alive.”

Enerolisa’s rousing spiritual chants first reached the mainstream on Rokabanda’s 1994 hit “Esa Mujer Abraza Mi Vida,” later taking a starring role on Kinito Mendez’s 2001 merengue blockbuster A Palo Limpio. Los Angeles indie-pop act Jarina de Marco interpolated the chorus of “Los Olivos” into her debut single “Main Dish,” while Arizona cumbia duo Los Esplifs built “Un Solo Golpe” on the rousing closing bars of one of her most famous compositions, “Lo Motorita.” Enerolisa was also featured on bullerengue matriarch Petrona Martinez’s 2021 Latin Grammy-winning album Ancestras, and Villa Mella rapper Inka just released a throbbing dembow titled “Palo” celebrating her enduring legacy.

While these references and collaborations underscore Enerolisa as a sage of Black diasporic music and spirituality, much of her work has sadly gone uncredited. The Dominican Ministry of Culture as well as the community of Mata Los Indios have mobilized in recent years to document and preserve as many of these oral traditions as possible. Enrique Minier of Villa Mella’s centuries-old Cofradía del Espíritu Santo teaches the craft of instrument-building, while filmmaker Boynayel Mota founded the Kalunga Cultural Center as a hub of learning and memory.

Enerolisa took a step back from the stage last year following a near-fatal stroke, and though she has slowly recovered, the incident is an urgent reminder to give our legends their flowers while they’re still here to smell them.

Best of Rolling Stone