‘Three Colors’ Revisited: Why a 30-Year-Old Trilogy Is This Summer’s Most Relevant Cinematic Universe

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In a 1995 documentary interview shot 10 months before his death in the middle of heart surgery at the age of 54, the great Polish filmmaker Krzysztof Kieślowski gave himself the kind of backhanded compliment that captured both his wry sense of humor and his cancerous frustration with the limitations of his cinema (or was it the cinema itself?). “I have one good characteristic,” he blankly confessed to the camera. “I’m a pessimist, so I always imagine the worst. To me, the future is a black hole. It frightens me.”

Then semi-retired at the height of his powers despite continuing to scribble away at a pile of scripts inspired by the afterlife, Kieślowski may have already suspected that he wouldn’t be around to experience much of the future for himself. Nevertheless, each new reissue or restoration of the fin-de-siècle film series that capped off his career makes it all the more obvious that Kieślowski understood some ineffable essence of the world to come more clearly than he may have realized or cared to admit.

More from IndieWire

In a fitting reflection of the happenstance that holds the various realms of the Kieślowski Cinematic Universe together, his “Three Colors” trilogy appears to arrive at its staggering power as if by accident. Most noticeably, its stories overlap in a way that seems at once both fatalistic and completely random, which allows Kieślowski and co-writer Krzysztof Piesiewicz to create spectacular deus ex machinas that feel like natural events, and mundane chance encounters that seem as if they’ve been arranged by the gods. But the paradoxes only grow more confounding from there.

Despite being spread across three different countries (and at least as many genres), Kieślowski’s final three films are inextricably bound together by the common struggle for self-definition in a world that’s tearing apart at the seams. Despite boasting a trio of “happy endings” — each of them murkier than the last — the trilogy’s separate chapters all reflect their director’s lifelong fixation with the ambivalent relationship between actions and their consequences.

Despite the 21st century becoming every bit the black hole that Kieślowski had imagined, the primary colors he saw amid the darkness of his own time are even more vibrant today. Rewatching these movies at a moment in history when tomorrow’s horrors seem almost preordained, I was overwhelmed to discover how the same uncertainty that once made Kieślowski so pessimistic about the future has become a perversely hopeful salve for those of us living in it, and lucky enough to watch the 4K remasters that Janus Films will be trickling into theaters nationwide throughout the rest of the summer.

“I’ve got an increasingly strong feeling that all we really care about is ourselves,” Kieślowski lamented toward the end, but his films — never sentimental, often cruel, but sometimes capable of rescuing pearls of hope from the clutches of pure tragedy — also betray a profound belief that we’re all responsible to each other in ways that no one person could hope to understand with the naked eye. Kumbaya as that concept might sound in theory, Kieślowski was keenly attuned to how bleak it could be in practice. Indeed, the “Three Colors” surges with an eerily prescient recognition that our self-interest would continue to scale at the same rate as our interconnectedness.

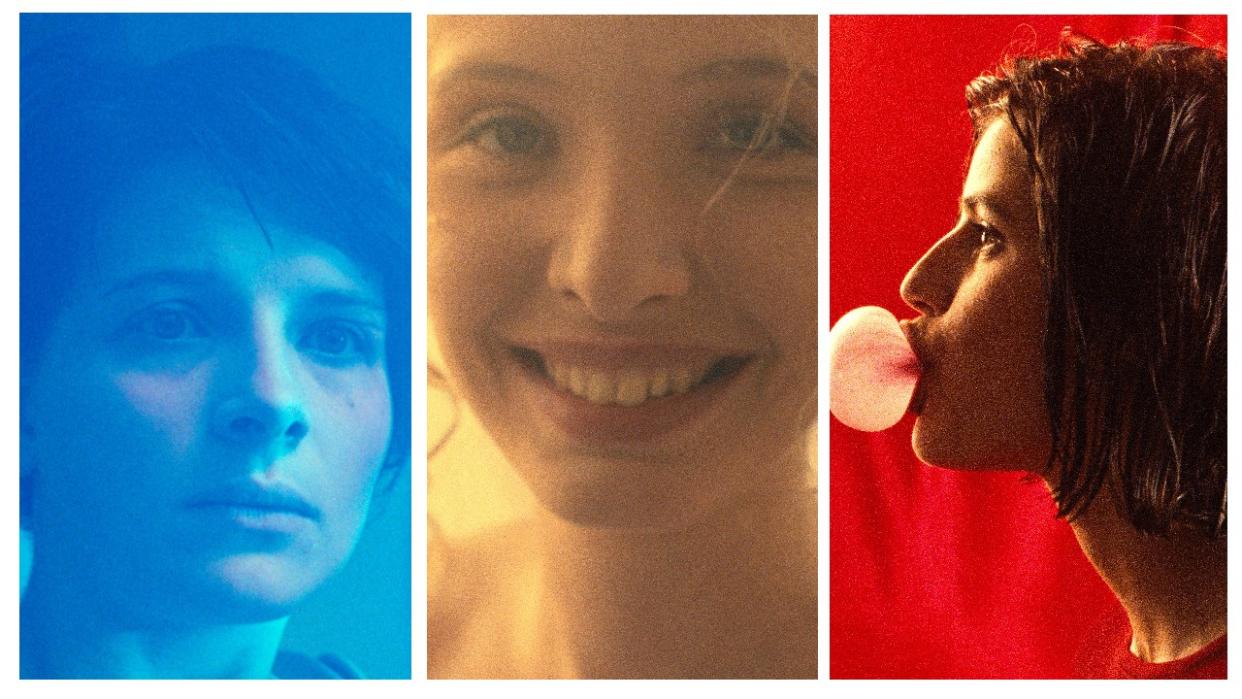

To start with the basics, each of the “Three Colors” (“Blue,” “White,” and “Red”) ostensibly embodies one of the political ideals championed by the motto of the French Republic (liberty, equality, and fraternity). Be that as it may, Kieślowski had a knack for subverting high-minded concepts, and he was always happy to admit that his trilogy’s most basic hook was reverse-engineered from the source of its financing.

Which isn’t to say these films don’t play on their pet themes in meaningful ways, but rather to reaffirm the argument that Kieślowski — in keeping with the spirit of the earlier film cycle he adapted from The Ten Commandments — was more compelled by the impracticality of those ideals than he was by their virtue. He was obsessed with how they might be warped by a society whose nascent interconnectedness was starting to reveal its natural solipsism, and vice-versa.

The enduring power of the “Three Colors” trilogy is not that it so elegantly identifies the ironies of a world that’s pulling apart as it grows closer together, but rather that it recognizes those ironies as their own potential avenues of connection. The cosmic rhymes these movies find within themselves and in concert with each other create a rare poetry from the (sometimes menacing) idea that none of us can ever be alone, and by doing so they mine a unique solace from the sheer unknowability of how we might mesh together.

The worse things appear, the more hopeful it is to watch a film that humbles us into realizing we may not understand the shape of our world as well as we might think. With his magnum opus, Kieślowski orchestrated three of them.

“Three Colors: Blue”

If the automobile crash in the first scene of “Blue” and the ferry sinking in the last scene of “Red” (alas, not the only Kieślowski film to end with a public transportation disaster) cleanly bookend the “Three Colors” trilogy into a single cohesive piece, each of these movies is effective as its own self-contained piece. That remains especially true of “Blue,” the series’ indelibly bracing first chapter, in large part because of how it was designed to echo across the two that followed.

A cacophonously intimate character study about a woman named Julie (a 29-year-old Juliette Binoche) who survives the car crash that kills her famous composer husband and their innocent young daughter, and then tries to cope with her loss by dissociating from the life she once shared with them, “Blue” introduces a fragmented world that the rest of the trilogy will strive to reassemble however it can.

The prologue is an unforgettable masterclass in cinematic pointillism, one that crystallizes Kieślowski’s genius for capturing the raw emotionality of banal — if also catastrophic — events. A tire whirs along a highway, creating a sound vacuum that swallows all other oxygen from the frame. A small hand sticks an aluminum candy wrapper out of a backseat window and holds onto it as it flaps in the wind. Julie’s daughter watches the traffic through the rear windshield, the tri-color road lights of a highway tunnel blurring into abstraction like stars melting over an astronaut’s visor as they get sucked through a wormhole. We don’t see her parents’ faces when the family pulls over for a rest stop, only the ominous, “Final Destination”-esque drip drip drip of motor oil dropping from the chassis. It’s as if the car were driving itself through a dream.

A young man plays with a wooden toy on the side of the road, his thumb so out-of-focus by the time Julie’s family zooms by that you can hardly tell he’s a hitchhiker. Later, it might occur to you that the ensuing car crash wouldn’t have happened if Julie’s husband had offered this stranger a ride. Kieślowski isn’t punishing him for that — his god has little appetite for divining right from wrong, and “Three Colors: Red” will eventually reaffirm the trilogy’s distaste for results-oriented morality — but the fractured and isolating way he depicts this terrible accident creates a strange dissonance when seen in context with the shockwaves that reverberate out from it.

This may be the most personal tragedy of Julie’s life, and yet it will never be possible for her to contain it within herself. It’s already too late for that.

Of course, that won’t stop her from trying. On the contrary, the brittle and ultra-subjective “Blue” unfolds as if Julie were inspired by the discrete nature of Kieślowski’s editing; as if the film’s impressionistic prologue reflected her own splintered memory of the crash, and invited her to separate the remaining pieces of her life in much the same way. Julie watches her husband and daughter’s funeral through the glass of a tiny hospital TV, and then, in the wake of a failed suicide attempt, begins to obsessively sweep the most painful shards of herself under the proverbial rug.

Liberated from her roles as a wife, mother, and muse (her exact contributions to her husband’s symphonies are left ambiguous, but it’s implied that she was more responsible for his genius than anyone realized), Julie puts the family estate up for sale, destroys the unfinished sheet music they’d been writing to mark the unification of Europe, and has sex with her dead spouse’s closest collaborator, effectively cauterizing the wound left behind by his loss. Julie then takes up an ascetic existence in Paris, a glimmering blue mobile she took from her daughter’s room the sole material connection to her previous life. It would seem out of character for Julie to visit her mother (Emmanuelle Riva), but the senile old woman implicitly reassures her that it’s possible to live in perfect solitude — to exist without memory.

Kieślowski isn’t convinced. He excuses his protagonist from any outward portrayals of grief (we never see her visiting a grave or flipping through old photographs, for instance), only to ambush Julie from inside her own mind. Passages of “her husband’s” incomplete symphony begin to haunt her like ghosts, sometimes erupting between her ears with such force that a scene will completely surrender to the music, fading to black mid-conversation for a few bars of Zbigniew Preisner’s almighty score only to fade back in as if returning from a fugue state.

Julie’s implosive efforts to become an island unto herself are also frustrated by the fact that people keep washing ashore, as Kieślowski takes ironic pleasure in the tidal pull of his protagonist’s supposed isolation. Her self-annihilation forces Julie to confront the depths of her suffering, just as her solitude allows Kieślowski to suggest that people are hopelessly interwoven to a degree that should humble us all.

Julie’s monastic existence is first interrupted by a return appearance from the young hitchhiker, and then by her budding friendship with a stripper named Sandrine (Florence Pernel), who’s despised by the other residents of their building and sees a shut-in like Julie as her only potential ally. It’s only because Julie visits Sandrine’s club that she sees a news story about her husband on TV, and begins to suspect that he may have been having an affair. She may be through with the past, but the past isn’t through with her.

And yet, Kieślowski is less interested in “Magnolia”-like coincidences than he is in refuting the idea that life is as self-contained as our subjectivity — or that of a film camera — can make it seem. The universe may not be orchestrated, but nothing exists beyond the reach of its music, and there’s no telling how any two orbits might overlap. Case in point: The note-perfect scene in which Sandrine, shaken to her core after spotting her own father in the crowd, absentmindedly fluffs a male colleague’s flaccid penis while confiding in Julie about her recent experience. It’s just one of the countless instances in which the films of Kieślowski’s trilogy, alone and together, locate someone with a severe case of Main Character Syndrome in the middle of a rich mosaic.

It’s also one of the countless instances in which “Blue” finds Julie being imprisoned by the absolute freedom that she pursues in the wake of becoming a widow — that finds her encased (sometimes literally) by the same liberty she hopes will absolve her of the love that she’s lost. Julie’s effort to cut the ties that she’ll never be able to sever results in the creation of new ones that she’d never be able to predict. In her frenzy to harden into one of the radiant blue jewels that dangle from her daughter’s mobile, she doesn’t hear the delicate sound they make as they brush into each other and refract the same light.

“I want no friends, no family, no lovers,” Julie tells her mother. “They’re all traps.” Her mother replies with a rare moment of lucidity: “One can’t give up everything.”

“Three Colors: White”

Unless, perhaps, they have nothing to lose.

Arguably the best movie ever made about the consequences of a trip to Ikea — sorry “(500) Days of Summer” — “Three Colors: White” adds a globalistic texture to Kieślowski’s project by telling the story of a hapless loser named Karol Karol (Zbigniew Zamachowski, looking like a doughy Jean Gabin) who celebrates the unification of the EU by losing his passport, getting cucked to hell and back by his hot French ex-wife, Dominique (a demonic Julie Delpy), and then smuggling himself back to Poland inside a suitcase that gets stolen by some crooked baggage handlers at the Warsaw airport. “Home at last!”

A rags-to-riches comedy that runs pitch-black despite what its title implies, “White” forms its cock-eyed vision of equality by following Karol’s efforts to get even with his ex. The film’s kooky plot chronicles his wild ascent from impotent sad-sack in a capitalist country to super-wealthy capitalist (and/or criminal?) in a recently Communist one, its story hinging on chance encounters, elaborate suicide attempts, and an opportunistic land grab involving a certain Swedish furniture corporation.

But the gallows humor of it all is grounded in Karol’s enduring fixation with the woman who laughed him out of divorce court, and the (vaguely Trumpian) perversity of building a powerful empire out of personal embarrassment. The closer our pathetic hero gets to exacting his revenge on Dominique, the more he realizes that he’s still in love with her. At the end of “Red,” Kieślowski doubles back to confirm that the same held true for Dominique — that being defeated by Karol is what convinced her that he was a worthy match.

The most overtly political installment of a series that sees politics as more of a context than a subject, “White” may not be much funnier than either of the other two films in the trilogy, but it is — by definition — the lightest, from the opening scene in which Karol gets shat on by a bird on his way into court, all the way down to the orgasmic white-out that’s triggered by Karol and Dominique posthumously consummating their marriage after his fake death and their real divorce.

While both of those moments are amusing, neither are necessarily deserved. “White” starts with a trial and ends at a jail, but true justice is nowhere to be found in between. If the film’s estranged lovers somehow wind up on a level playing field, it’s only because of their shared desire to be more equal than each other (a darkly comedic notion that Kieślowski cribbed from his experience with Communism).

In a world where true equality no longer seems possible and everyone is simply acting in opposition to someone else, mutual self-interest might just be a sustainable recipe for love.

“Three Colors: Red”

If “White” finds that self-interest can hide love, “Three Colors: Red” argues that altruism can disguise self-interest. The most intricately plotted chapter of the trilogy, as well as the one that most deepens its mysteries, Kieślowski’s last film tells a knotted story about the unusual friendship that forms between a part-time model who’s paid to be looked at (Irene Jacob as Valentine) and a retired old judge with a penchant for voyeurism (Jean-Louis Trintignant as Joseph).

It’s a story of fraternity that points outward with the same force that “Blue” folds in, as Kieślowski explores the potential for true connection in a hopelessly tangled world where everyone — not just the grieving wife of a famous composer — is siloed away from each other by their own subjectivity. “Red” does so by adhering to a different but similarly intimate sense of musicality, using sound to isolate its interwoven characters in a way that a modern remake might rely on screens.

Among the most lasting images in a movie that boasts several iconic shots: Valentine listening to an album in a crowded Geneva music store and wearing a pair of massive headphones that make her oblivious to all of the other people around her doing the same thing. Two of those other people (law student Auguste and his cheating girlfriend Karin) happen to be the subjects of a parallel storyline that only spills into Valentine’s life through chance implication and the occasional camera move; she will hear their voices without ever knowing to whom they belong, or what they might be trying to tell her.

In that respect and several others, Kieślowski’s last film is singularly attuned to the complex, bizarre, and even supernatural network of echoes that reverberate throughout our world. Typical of the trilogy that it brings to a close, the film opens with a virtuosic sequence that finds the movie on its most literal note: We see a man’s fingers punching a few digits into a landline phone, and then follow the call as it races through the wires, under the surface of the ocean, along a maze of cement tunnels, and then into an abstract swirl of lights and sounds before it finally rings through on the other end of the line a few milliseconds later.

If such vast infrastructure is required just for one person to deliberately make contact with another, how can we hope to understand the infinite twists of fate that bring perfect strangers into each other’s lives, or predict how the choices they make will reverberate across several lifetimes to come? As Kieślowski framed the essential question of the film: “Is it possible to repair a mistake that was committed somewhere high above?” That Valentine and Joseph cross paths at all seems to result not from divine intervention so much as a resistance to it; note the composition of their first encounter, which finds Valentine walking up behind the unsuspecting Joseph in his own house as if the script itself has been taken by surprise.

Like most of the questions raised by the “Three Colors,” Kieślowski’s is left unanswered. “Everything happens for a reason” cuts both ways in a trilogy where cause is estranged from effect, and people are often as mystified by themselves as they are by the world at large. That’s especially true of “Red,” the only film of the trilogy in which Kieślowski attunes his audience to cosmic wavelengths that his characters can’t hear — creating rhymes between them that only we are able to notice (dissonances too, as becomes clear when Joseph challenges Valentine to tell his neighbors that he’s been eavesdropping on their calls).

In that light, the brain-like fibers of those blue, white, and red wires in the opening sequence provoke some open-ended questions of their own: If actions and consequences are hopelessly garbled across a cosmic game of telephone, does the same hold true within ourselves? Does why we do things have any moral bearing on the outcomes of our choices? And how could we even claim to discern the difference between right and wrong in a world where miracles are indistinguishable from catastrophes?

The Coda

The genius of the coda that Kieślowski and Piesiewicz invent for “Red,” and by extension the entire “Three Colors” trilogy, is that it somehow choreographs an honest emotional gut-punch from a choppy sea of ambivalence.

Joseph, already paranoid that Valentine might drown in the same waters that claimed his one true love several decades before, watches the television news in horror as it’s reported that more than 1,400 people have died aboard a ferry that capsized along the English Channel. His relief upon discovering that Valentine is one of only seven survivors mirrors our own, which is heightened several times over by the realization that Julie, her new partner, Karol, Dominique, and Auguste make up five of the other six living passengers.

To us, this would seem like a happy ending. To the countless people who had similar attachments to the dead, probably not so much. Our allegiance to these particular characters is as random as the unknown bartender who makes it to safety alongside them; our emotional response to their survival is both honest and selfish in equal measure. This isn’t a biblical case of righteous souls being spared from God’s wrath, but rather an act of chaos that’s been flavored with pinches of mercy.

We are just like Joseph, the old hermit’s face pressed up against his own reflection in the TV screen as he salvages an irrepressible glimmer of light from the darkness of his own premonition. And Joseph is in turn just like Kieślowski, whose life’s work ends with seeing flecks of color inside the black hole that stretched before it.

As the world grows smaller, the universe will continue to seem like an increasingly apathetic place, but the apathy it breeds among the people who share it will always be answered by the silent echoes that reverberate between them. Life is still capable of surprising us, “Three Colors” insists, even after it’s over.

If that’s what passes for hope these days, then so be it. As a street performer tells Julie: “You gotta always hold on to something.” It’s unclear if she hears those words or not, but it ultimately doesn’t matter — they continue to resonate through us.

“Three Colors: Blue” is now playing at Film at Lincoln Center. It will expand nationally throughout the summer, followed by “White” and “Red.”

Best of IndieWire

New Movies: Release Calendar for July 8, Plus Where to Watch the Latest Films

All the Details on 'Hunger Games' Prequel 'The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes'

The 35 Best Romance Movies of the 21st Century, from 'High Fidelity' to 'Carol'

Sign up for Indiewire's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.