Hozier on solitude, relationships and his new album: ‘I think everyone goes through their version of hell’

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Hozier is being buried alive. Dirt covers his face, scatters across his eyes, until only his mouth is visible, a daisy clenched between his bared teeth. To the average onlooker, it’s an alarming sight to behold. For those who know the Irish artist’s music, it’s par for the course. This is the cover art for his third album, Unreal Unearth. Photographer Julia Johnson told her followers it was one of the most “stressful shoots of her life”. But judging by his wide grin, Hozier was having a grand old time.

The musician born Andrew Hozier-Byrne can frequently be found communing with nature. To affectionate fans, he’s some kind of woodland sprite who sequesters himself in the Irish countryside – writing songs and occasionally sharing Instagram videos of himself marvelling at badger sets or rolling down hills – until it’s time to tour again. In his lyrics, nature grips him with long, tenacious fingers, plaguing him with visions of the creatures roaming about the earth. Yet Unreal Unearth is also shaped by the fears and anxieties of lockdown, during which it was largely composed. “It was funny, because in some ways I thought I’d spent enough time [on his favoured themes of life and mortality], and then we were thrown into these new conditions,” the softly spoken 33-year-old says. “So there was a lot of death hanging over me.”

We’re sitting in his dressing room backstage at L’Olympia, the historic Paris venue where he’ll be performing tonight in front of a 2,000-strong audience. He’s dressed casually in jeans and a striped shirt, while his wild dark mane of hair is tied back, a few wayward tendrils escaping to frame his face. His calm, cerebral demeanour is more medieval poet than rock star. It’s fitting, given Unreal Unearth was inspired, in part, by Dante’s Inferno – the first part of the 14th-century Italian poet’s narrative work, The Divine Comedy.

During lockdowns, Hozier holed up at his late-1700s house in County Wicklow, with books, epic poetry and the stark beauty of the Irish coastline to keep him occupied. “I was confronted with things that were working in my life, and things that weren’t,” he recalls. “Things were changing and shifting. People, careers, habits, places… relationships around me were breaking down and forming in new ways.” Dante’s Inferno was one of the texts that stuck with him, along with the Greek word “katabasis”, meaning a journey into the Underworld. “I think everyone goes through a version of that in their lives.”

Hozier was once lumped into an entire genre of male singer-songwriters including Ed Sheeran, Lewis Capaldi, Tom Walker and George Ezra that was described in 2019 by Radio 1’s Chris Price as “variations on man-with-guitar-singing-sad-songs”. Yet it seemed ludicrously shortsighted to suggest that Sheeran’s insipid slow jam “Thinking Out Loud” or Ezra’s twee bop “Budapest” came close to a song like “Take Me to Church”. Hozier’s debut single, a gospel-backed howl of protest against religious hypocrisy, propelled him to global fame and was nominated for Song of the Year at the 2015 Grammys. “I’ve had a few delightful open letters from pastors who have a few choice words to say,” Hozier told The Guardian that same year, amused by religious leaders who were disappointed to learn it wasn’t actually a song about attending your local chapel.

Many of the songs that followed had a devotional, romantic quality, yet Unreal Unearth is darker, and sees Hozier venturing down into his very own circle of hell. Far from a concept record, the album serves as Hozier’s own guide, leading him through the ruins of a relationship, and the crumbling world around him, towards a place of light and hope. He’s wonderfully morbid on the single “Eat Your Young”, a contemporary riff on the Irish writer Jonathan Swift’s 1729 essay “A Modest Proposal”, a satire taking aim at social attitudes towards those in poverty. With lyrics that include “seven new ways to eat your young”, it’s Swift meets Sinead O’Connor (the Irish artist died after this interview, with Hozier paying emotional tribute to her during a live show in Belfast).

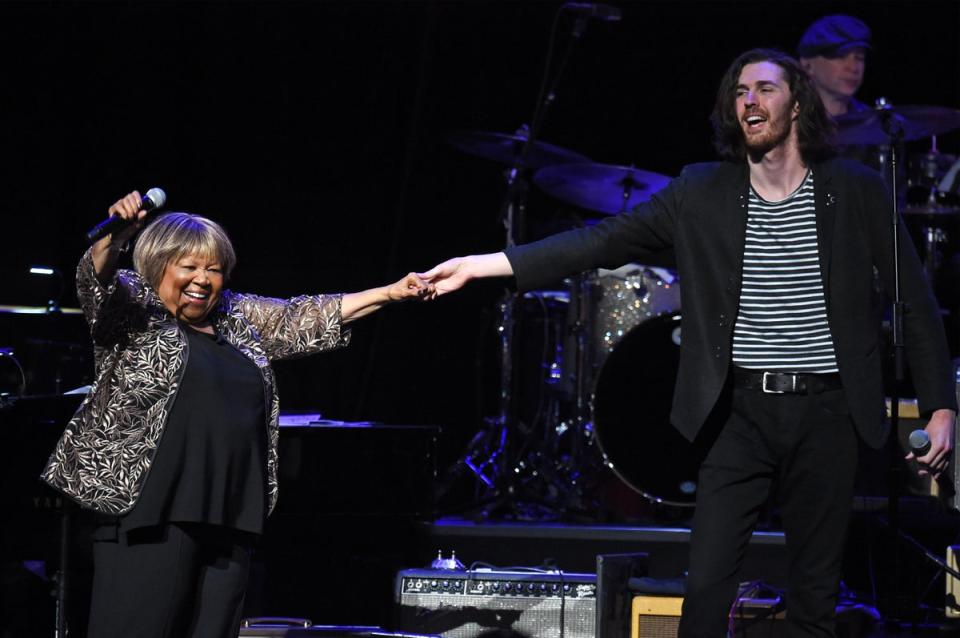

Like O’Connor, Hozier uses his music as a means of political protest. His parents – an artist and a blues drummer/banker – raised him on a diet of soul, folk and blues; his past songs have delved into everything from abortion laws to the civil rights movement. Songs such as “Nina Cried Power”, a collaboration with gospel singer and activist Mavis Staples, paid tribute to Nina Simone but also Patti Smith, Billie Holiday and Woody Guthrie – all of whom he’s cited as heavy influences. His singing style, too, is clearly inspired by the earth-trembling vocals of Aretha Franklin and Etta James, his voice as capable of hitting a diaphanous falsetto as it is swooping down to an almighty bellow.

He likes to take his time with each new album: Unreal Unearth is only his third record in a decade. But this time, he found himself working with co-writers including Jennifer Decilveo (Angelique Kidjo, Miley Cyrus), and, more surprisingly, enjoying it. “I’m somebody who is constantly trying to crawl away and be on my own, but to the point where I could end up losing my own mind,” he says. “It was a drug, to come from such solitude and then be in a space with others, making all this fantastic noise.”

Initially, he was concerned that he might be misunderstood if he let his co-writers in too early; that the layers of meaning he tends to put into his songs could be lost. He needn’t have worried. The lyrics on Unreal Unearth are arrestingly poetic, often abstract in the pictures they paint, and inspired by surrealist texts such as Irish writer Flann O’Brien’s philosophical 1967 novel, The Third Policeman. There’s history, too: “Butchered Tongue” is a haunting folk song that references the torture of Irish rebels by the British during the Wexford Rebellion of 1798, and, more broadly, the extinction of indigenous languages across the world at the hands of colonialism.

“[Butchered Tongue] is about the sorrow of how much can be lost but also, from an Irish perspective, how fortunate we are to have a written history – we have a means of looking back and drawing from our history in a way that many indigenous cultures can’t,” Hozier says. There’s conflict of a different sort on “Who We Are”, about two people who ended up inflicting pain on one another. “People bring their own turmoil, unknowingly, into a relationship. It’s crunchy, and hard…” A small, exasperated chuckle escapes him. “It’s not roses.”

He keeps his private life just so, but there are clear references to the end of a relationship in other songs such as “Francesca”, which takes its name from a canto (song) in Inferno, and “Unknown / Nth”, a wrenching portrait of grief for the loss of someone who once knew him intimately. Over rich acoustic strums of the guitar, he sings in a forlorn half-whisper: “You know the distance never made a difference to me/ I swam a lake of fire/ I’d have walked across the floor of any sea.” On the chorus, he mourns that person, now gone, leaving him feeling unknown once more.

“It’s devastating,” he says, with a soft shudder of breath, staring at the ground. “I was channelling that feeling of coming out the far side of such admiration and such worship, and that feeling of being let down and having your expectations dashed.” This feeling also sits in Dante’s Ninth and worst circle, reserved for those who have betrayed the trust of someone close.

“We betray ourselves in the act of opening up to somebody and believing so much,” Hozier says, passing a hand across his face. He looks weary, all of a sudden, voice cracking a little. “Our eyes betray us, our hearts betray us, our minds betray us. And that’s the ‘Nth’ reference: we open ourselves up to something, only to betray ourselves…”

I’m a musician, so my relationships are only ever at a distance

It must be hard, trying to know someone enough that a relationship can be sustained no matter the length of time apart, or distance. “Yeah, and I’m a musician, so my relationships are only ever at a distance,” he responds with a shrug. “It’s tough, because you’ve got to bring yourself fully to it – you can’t do things by halves.”

No one could accuse Hozier of doing things by halves, at least not on Unreal Unearth. The final song on the album is the final step in his odyssey, led by an Italian-style tarantella. “There’s reconciliation in the song,” he says. “It’s like seeing the sky for the first time.” It mirrors the moment Virgil leads Dante out of hell, as Hozier sings: “The sky set to burst/ The gold and the rust/ The colour erupts/ You filling my cup/ The sun coming up.” It’s as though he discovered, after a long journey down, that even hell has a way out.

‘Unreal Unearth’ is out on Friday 18 August