The Wild Story of Disco 'Star Wars': How the Universe Aligned to Create Meco's Masterpieces

The best-selling Star Wars music of all time wasn’t recorded by John Williams, nor was it sanctioned by George Lucas. No, the unlikely hit was a slice of pure disco, mashing up the movie’s main title and Cantina theme.

For your listening pleasure, may we present Meco’s “Star Wars/Cantina Band” — a serendipitous mix of talent and timing that begat its own musical franchise, and involved a slew of boldfaced names-to-be, including the future bandleader of Dancing With the Stars, the Tony-winning composer of Nine, and Jon Bon Jovi.

Our tale begins, as Star Wars stories do, a long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away… In this case, New York City circa the late 1970s. Domenico Monardo, a 39-year-old virtuoso trombonist turned music producer known by the nickname Meco, made a 20-block trek downtown to see a strange, new film. “I was a big science-fiction fan. I would go see all the movies,” Monardo recounts to Yahoo Movies from his home in Florida. “I went to the first showing of Star Wars at the one theater in Manhattan that was playing it, and immediately fell in love with the film. I thought it was absolutely fantastic. I went back and saw it three times the next day!

“That’s when the music really hit me me,” recalled Monardo, who by that point had worked with such early-era disco artists as Gloria Gaynor and Carol Douglas. “I was humming it like crazy when I left the theater, whistling the theme. … I called some record companies and said, ‘I want to take that music and dance to it.’”

Cold-calling labels and pitching danceable space songs worked about as well as you’d think (at least one executive told Monardo to “get lost”). But Neil Bogart, the head of Casablanca Records, didn’t immediately hang up, and agreed to see the movie before making his decision. A few days later, Bogart — whose roster included KISS, Donna Summer, Cher, Village People, and Parliament — called Monardo back. They had a deal.

Now he had to figure out how to make the music. With the movie in theaters only a few days, John Williams’s score wasn’t publicly available. So Meco worked his magic on the phone, sweet-talking a receptionist at 20th Century Fox’s music publishing division into sending the score, and sealing the deal with a dozen roses.

Meco assembled his partners: Tony Bongiovi, a producer who’d worked on several disco albums, plus records with the Ramones and Talking Heads, and Harold Wheeler, an ace arranger who in later years would serve as musical director of the Oscars and Dancing With the Stars. Meco then hired a 70-piece orchestra (“to recreate the sound of John Williams and the London Sympony”), with himself on trombone.

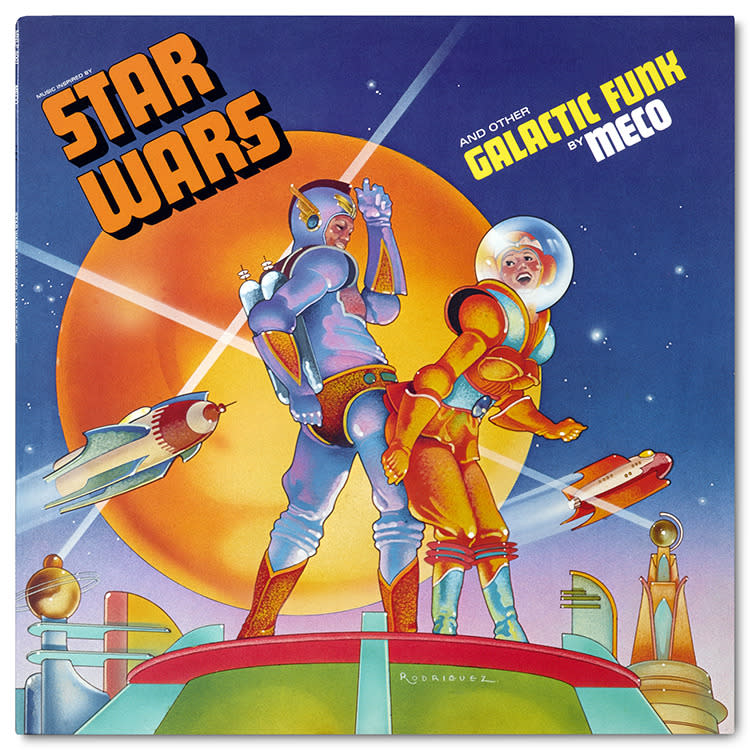

The album’s A-side would be an uninterrupted medley of Star Wars music comprising the “Title Theme,” “Imperial Attack,” “The Desert/The Robot Auction,” “The Princess Appears,” “The Land of the Sand People,” “Princess Leia’s Theme,” “Cantina Band,” “The Last Battle,” and “The Throne Room/End Title” set to a disco beat with a generous sprinkling of lasers, spaceships, droids, and other sound effects. The B-side contained three throwaway tracks, called “Other Galactic Funk,” unrelated to the film.

The full 15-minute A-side of ‘Star Wars and Other Galactic Funk

Team Meco painstakingly reproduced the movie’s sounds using primitive synthesizers and laborious techniques. Getting R2-D2 right took eight hours. “I didn’t get the sound effects [from Lucasfilm],” explains Monardo. “You have to remember, at this point, George Lucas didn’t know I existed.”

“We finished the album and the first side was 15 minutes long, which was common with disco music. But we had to make a single. So I used the intro, the first part of the main theme… and then I cut to the Cantina section, then back to the theme. As soon as I played [it], we knew it would be big.”

For the distinctive album cover, Meco says he dreamed up the idea of two astronaut types grinding against each other. Illustrator Robert Rodriguez, who updated the iconic Quaker Oats packaging in the 1970s, created the artwork. “I actually tried to get out of doing the job because the deadline was cut from one week to three days,” Rodriguez recalled on his blog. “No sleep and three days later, we were finished. It was a fun project, though I always wished for more time to do a better job, but people seem to like it.”

The ‘Star Wars and Other Galactic Funk’ cover by Robert Rodriguez (Rodriguez FineArtPrintsCA)

Speed was essential: the Jedi masterminds behind the project needed to get out the album while the film was still going strong. Music Inspired by Star Wars and Other Galactic Funk was released on Millennium Records, an imprint of Casablanca, in the fall of 1977, just four months after Meco’s fateful trip to the cinema. By October, the album hit No. 13 on the pop charts on its way to 1 million-plus sales, outperforming Williams’s official Star Wars soundtrack. The single, “Star Wars Theme/Cantina Band,” did even better, topping the pop charts and selling more than 2 million copies in the U.S. — still a record for an instrumental track — and 4 million copies worldwide. The influx of cash allowed Bongiovi to construct the legendary Power Station recording studios in New York.

The commercial success didn’t go unremarked by the music industry: Meco’s “Star Wars Theme/Cantina Band” was nominated for the 1978 Grammy for Best Instrumental Recording. However, Monardo lost out — to John Williams and the London Symphony’s version of the “Star Wars Theme.” Meco took the loss hard. “John Williams got word about it. … He sent me a plaque, a 2-foot by 4-foot double-sided plaque. One side had my Billboard standings, showing my ‘Star Wars’ at No. 1. The other side was my album cover and a beautifully handwritten note: ‘Dear Meco, thank you so much for this marvelous version. Sincerely, John Williams.’”

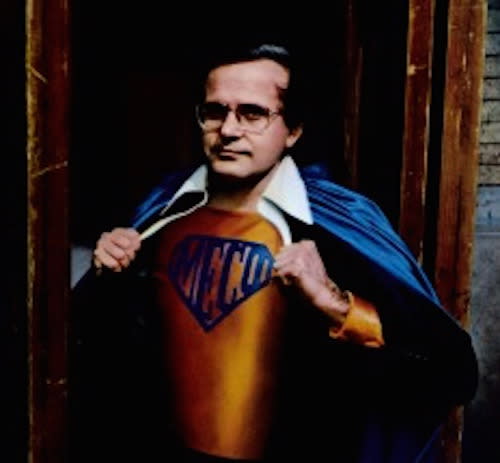

Meco makes like a superhero on cover of his ‘Superman and Other Galactic Heroes’

After the success of his Star Wars cover, Meco recorded disco-fied versions of Close Encounters, Wizard of Oz, and Superman themes, among others. And he might have been the biggest pop star nobody saw; Meco never went on tour, never fronted a music video, and only made one TV appearance, which was completely unrelated to his Star Wars recordings. (He and his band performed their Oz music on Dick Clark’s primetime variety show.)

By 1980, Casablanca had imploded, and Meco found himself on a new label: Robert Stigwood’s RSO Records, whose biggest act was the Bee Gees. At this point, Meco was finally on Lucasfilm’s radar. He worked the phones again until he was able to get resident soundman Ben Burtt to provide effects for Monardo’s next cover, “Meco Plays Music From The Empire Strikes Back.” This time all the blasts, lightsaber swings, and R2-D2 chirps were authentic, even if the music wasn’t quite the same.

“Disco was dying,” says Monardo. “It was 1980. We made it more rock.” The medley of Empire motifs, showcasing “The Imperial March,” was another hit, peaking at No. 18.

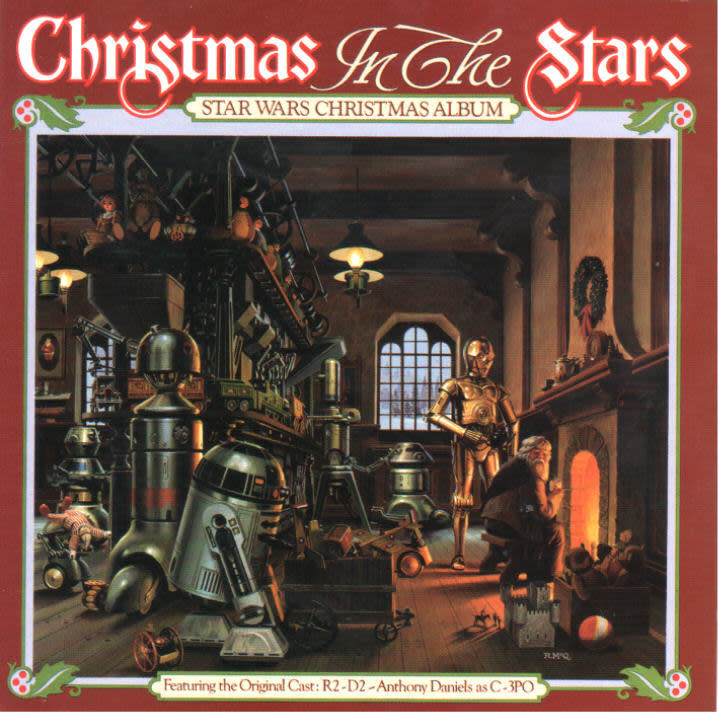

Bolstered by his latest Star Wars-related smash, the never-shy Monardo decided to swing for the fences. “I wrote a letter — I think it was nine pages long — to George Lucas. I said, ‘You don’t know me,’ and then I explained about all the Star Wars music I did… I said, ‘Why don’t we do a Christmas album together.’

“Then I had the only phone call I ever had with George Lucas. I did most of the talking, but he told me some ideas, and what we could use.” Lucas, apparently unconcerned about the previous Star Wars holiday effort, delivered: he permitted Burtt sound effects to be used, flew in Anthony Daniels to “sing” C-3PO’s songs, and had Oscar-winning designer Ralph McQuarrie paint the album cover.

Ralph McQuarrie’s artwork for ‘Christmas in the Stars’

Lucas even dispatched Darth Vader (at least a guy in a Darth Vader suit) to a recording session at the Power Station. “I realized that George Lucas had sent Darth Vader to make sure everything was going right,” quips Meco.

Darth Vader gets instruction from Meco (Meco Monardo/TheForce.Net)

“We were in good favor with George Lucas, because there’s royalties that get paid to John Williams and George Lucas and all those other people,” Bongiovi recounted to the CBC last year, adding that they could have had access to stars Mark Hamill, Carrie Fisher, and Harrison Ford but “they’re not singers, so they don’t fit on a record album.” The producers did want to bring in Frank Oz to croon a song called “The Meaning of Christmas” as Yoda, but he was tied up filming The Great Muppet Caper.

Unlike his previous albums, Meco started from scratch with the music. He and Bongiovi needed Star Wars-themed Christmas songs and they needed them fast, but they weren’t having much luck with the songwriters they approached. Enter a struggling composer named Maury Yeston, who was trying to put together the musical that would become Nine and could use the extra cash. “I met with Meco and I said, ‘Look, this may sound ridiculous to you, but if you want to do a Star Wars Christmas album you have to have a story,” Yeston told the CBC. “This is obviously Christmas in the world of Star Wars, which means this is in a galaxy far, far away, thousands of years ago. It’s not now. So call it Christmas in the Stars.” Meco was sold on the idea of the album having a through-line and recruited Yeston.

Yeston, who would win a Tony for Nine and eventually write the hit Broadway musicals Titanic and Grand Hotel, cranked out nearly 20 Yule-appropriate tunes, nine of which made the final cut. Among them, the Daniels-warbled title cut; “What Can You Get a Wookiee for Christmas (When He Already Owns a Comb?),” the single that reached No. 69 on the charts; a retooled “Meaning of Christmas” (Lucas didn’t want any overtly religious lyrics associated with the Force); and the ditty “R2-D2, We Wish You a Merry Christmas,” which marked the inauspicious debut of Bongiovi’s teenage cousin, a wannabe singer named John.

“He was sweeping the floors, and his cousin Tony said he could sing,” Monardo says of the artist who would rebrand himself as Jon Bon Jovi. “But he denied it forever and forever.” Bon Jovi reluctantly came clean to Forbes. “[Meco] needed a kid,” the rocker admitted. “So he said, ‘Can you really sing?’ I said, ‘Yeah,’ and he said, ‘Do it.’ So they wrote me down like a session musician … It took 20 minutes, there was nothing to it.” Bon Jovi got $180 for his first professional recording, fronting a kid chorus four years before his namesake band would have a breakout hit with “Runaway.”

RSO anticipated a huge demand for Christmas in the Stars and pressed a stunning 150,000 initial copies. But, like Casablanca before it, the label had serious issues and was abruptly shuttered (“Stigwood was screwing the Bee Gees out of money,” says Meco), meaning there was virtually no promotion for the album. The shutdown also denied a second run that would have featured a tweaked cover crediting Lucas as a co-producer at the request of the filmmaker, who, according to Meco, “liked the record.”

Undaunted, Meco was back, on yet another label, Clive Davis’s Arista Records, for 1983’s Return of the Jedi. His rendition of “Ewok Celebration” (a.k.a. “The Yub-Yub Song”) peaked at No. 60.

After that, with muse Lucas and the Star Wars series seemingly idled, Monardo moved to Florida and became a commodities trader. “Then in 1999, I got a call from CBS/Sony Records [which was issuing the soundtrack for The Phantom Menace]: ‘There’s a new Star Wars movie coming out.’” He was ready to fire up the Meco machine and get back to the studio, but his plans for new music came to a screeching halt. “It turns out John Williams had a clause in his contract saying nobody can put out a version of his music on his label without permission,” the producer says, the hurt obvious in his voice after 15 years. Although he remained sidelined while Phantom Menace, Attack of the Clones, and Revenge of the Sith rolled out, Monardo learned how to make music on his computer, and he decided to release one final ode to his favorite film series.

“It’s called Star Wars Party,” Meco explains of his 2005 album. “It’s music you can dance to, but about Star Wars characters.” The digital-only collection, available via sites like iTunes and CDBaby.com, featured versions of his Star Wars and Empire Strikes Back singles along with original compositions with titles like “Boogie Wookiee” and “I Am Your Father.”

‘Star Wars Party’ album cover

“That was the last professional thing I ever did,” says Meco, who just turned 76 and says he still plays music with friends. Asked if he’s excited about The Force Awakens and the prospects of making new Star Wars material, Meco doesn’t equivocate.

“No. The last film I ever saw [in theaters] was in 2005, the last Star Wars [Revenge of the Sith]. I’ll probably watch [The Force Awakens] when it’s on cable, but I won’t go to the theater to see it. Those days are long gone.”

But disco Star Wars is forever.