Texas DPS chief spent a career focused on protection. Now questions about Uvalde are looming

Steve McCraw has spent a lifetime trying to protect somebody in trouble.

His three younger brothers, from other kids who made fun of their worn out clothes. His classmates from the bullies of the crosstown rival school.

He spent a career targeting Mafia drug rings and international heroin smuggling outfits, rising through the ranks of the FBI and eventually to the director’s job atop Texas' Department of Public Safety.

He has waded into controversial policing efforts from the U.S.-Mexico border to the streets of south Dallas. He brushes aside political criticism with the same restraint that kept him safe undercover.

He is blunt, answers questions quickly and says the most when talking about the inherent value of law enforcement. The way it protects those who need it. The way the mere presence of a police cruiser, “a black and white,” can stop a car accident before it begins. Or even stop a murder.

Yet somehow on May 24, every one of those ideas – every inherent value of law enforcement, every promise of protection, everything – failed.

A teenage gunman walked into a pair of classrooms at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas, and officers raced to the scene, armed and armored, 376 in all.

Yet they waited for more than an hour – until after the next rounds of gunfire, until after students called 911 for help again and again, until after two teachers and 19 children were murdered – before agents from the U.S. Border Patrol stormed the classroom and killed the shooter.

More: In Uvalde, moments of silence, yet so much left to say

Soon, DPS’ Texas Rangers became investigators of the tragedy, and McCraw became the narrator of record.

And as he did, he took on a surprising role in law enforcement: one police leader openly, repeatedly criticizing another.

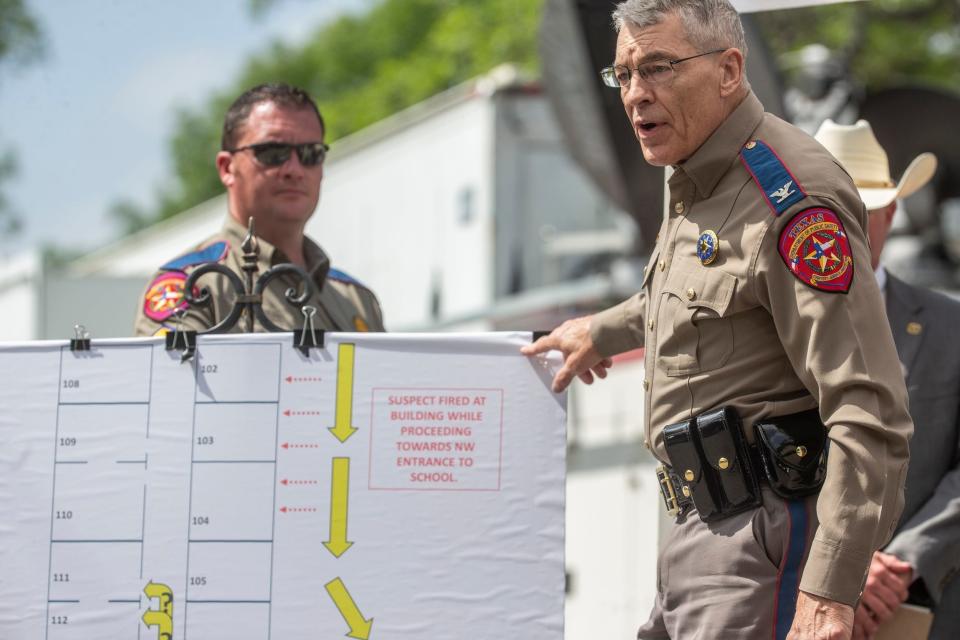

It was McCraw’s account, in a press conference several days after the shooting, that established the first public version of the policing failure.

And it was McCraw who first critiqued the man who would become the subject of all public blame: Pete Arredondo, the school district police chief.

The public hung on McCraw’s words, first at his Uvalde press conference, and then in his testimony at the state Capitol. His assessments heavily influenced the reports by both the Texas House of Representatives and the state’s premier police training experts – both of which faulted the overall response, but focused on the leadership roles of local police and made almost no mention of DPS.

As the events came into focus, though, more began to ask whether McCraw, the critic, had something to protect: his own agency’s actions.

Over the months, it has become clear that DPS troopers were intertwined with the Robb Elementary response more extensively than any early reports had showed.

Body-camera video shows troopers arriving alongside some of the first local officers inside the building. Dozens more arrived, until DPS had 91 officers on scene, the second largest number among the 23 state, local and federal agencies there.

Yet the first official report, from the state’s training center as commissioned by DPS, barely made any mention of the agency at all.

State Sen. Roland Gutierrez, whose district includes Uvalde, quickly became one of DPS’ most public critics, accusing McCraw of trying to deflect blame so people wouldn’t realize the agency “didn’t do a damned thing” to rescue the kids.

“I think the whole world was bamboozled by this goddamn DPS narrative,” he said.

Gutierrez believes the director should step down.

“Do I think he should retire?” Gutierrez said. “The answer is, yes. I think what happened May 24 was an abject failure by every agency there, including the Department of Public Safety.”

As the three-month mark passed and Uvalde children returned to school for the first time this month, the questions about DPS came to a head.

The Texas Tribune-ProPublica published an article questioning why DPS troopers hadn’t taken control in Uvalde, noting that DPS had led or co-led responses in previous deadly disasters.

TV station KXAN obtained notes from a mid-August DPS meeting, which describe McCraw as saying “no one is losing their jobs” over the response to the shooting. McCraw later told CNN that he had been misquoted and that “no one gets a pass.”

And DPS announced it had referred five of its officers, who had been on the ground at Uvalde, for an inquiry by the Office of the Inspector General, which conducts the agency's internal investigations.

DPS officials on Friday told USA TODAY that two more officers had also been referred. The agency declined to say why those seven had been singled out.

While it confirmed two of the referrals were among the "command staff," the agency has not publicly detailed what information various DPS leaders knew during the standoff.

No comment from McCraw appeared in most of the recent news reports.

But over the course of two interviews with USA TODAY, the state’s top cop described his life, his work and his agency’s role in Uvalde.

McCraw described an early scene where he says DPS leaders were getting fragmented and wrong information, and did not know children were in danger.

They were preserving crime scenes outside the school, including the shooter’s crashed vehicle and the house where he shot his grandmother in the face. They were pulling children out of classroom windows and pushing parents back to keep them from getting shot.

But in the end, when Border Patrol agents finally shot the killer and officers entered classrooms 111 and 112, McCraw says they realized how desperately wrong they had been.

“They’re pulling dead children out,” McCraw said. “They were mortified and sick. Even today.”

Throughout the 77-minute standoff, the agency's troopers never seized control of the chaotic scene.

Asked directly why they didn't, he says: “I wish we would have.”

Today, McCraw stands by the idea that the agency is his responsibility. He says he’ll resign if it’s clear the department responded inappropriately, noting that he serves at the pleasure of the governor.

“I don’t own this job,” he said. “We serve the public. That’s clear.”

Gov. Greg Abbott firmly supports the DPS leader.

“It is because of law enforcement officers and leaders like Director McCraw that the future of Texas remains secure,” Abbott said in a statement to USA TODAY.

Those who know McCraw personally say they believe the state’s top cop did everything he could, has survived far more than any politician could ever dish out and won’t be bullied by anyone.

“Right now he’s being painted as a coldhearted law enforcement guy,” said Doug Youngs, who has been friends with McCraw for more than 50 years. “There is a distinct human side of him that needs to be shown.”

Steve McCraw: Growing up ‘Wildman’ in El Paso

Sixteen-year-old Steve McCraw showed up in El Paso in 1970 with a chip on his shoulder.

The hot-tempered teen was coming from Stockton, California, where life with his mother and three brothers had been chaos. Money was more than tight. In the summers, he said, he went barefoot because the family couldn’t afford new shoes. In the winter, he had no heavy coat, so coaches lent him theirs. His frayed jeans always needed patches.

But no one got away with teasing him or his brothers.

“I got by with, you know, fighting,” McCraw said. “Shouldn't have, but did.”

As he grew older, the brawling continued. He barely tried in class. He and his mother clashed over the kinds of things that split troubled families apart.

Finally, he left his mother to live with his father, a colonel at Fort Bliss, the army base in El Paso.

And when he got there, he stepped into a whole new life.

James Cordell McCraw – “Mac” to his friends – was not a man to be trifled with. The Army colonel, once a stellar football player at Texas Western College (now the University of Texas at El Paso), lived by a strict code of discipline.

Steve would go to school. He would bring up his grades. He would do chores. He would stop fighting.

McCraw saw his father as an intimidating, forceful figure who demanded hard work. The teen’s new friends rarely came by the house because his father would always make them dig holes or chop wood.

McCraw settled into Burges High School. He was blond, blue-eyed and 6 feet tall. One girls' social club named McCraw their “sweetheart,” which basically required him to attend their meetings and give each girl a kiss goodbye at the end.

“When he walked in a room and there were girls, they were the ones that turned around,” Youngs said.

But despite the friends, the ladies, the structure, better grades and firm hand at home, one thing didn’t change. McCraw kept fighting. His friends called him Wildman McCraw.

He’s not proud of it, he says now. But back then, he says, fighting was seen as more of a sport, and less of a violent crime than it is today.

Not to McCraw’s father. Fighting was banned.

That didn’t stop the brawl at the bus stop.

Two teens from nearby Jefferson High School regularly came to the school to taunt the Burges kids as they boarded the buses. One of them made the mistake of kicking McCraw in the back.

It was a long fight, McCraw said, two against one. And in El Paso, he said, people pulled off their belts to use the heavy buckles as weapons, so it was a painful one.

And when it was over, McCraw sent the bullies on their way, pulled himself together and climbed on the bus.

“When he got on the bus, everybody clapped for him,” Youngs said.

Bloodied, McCraw trudged home, ready for his punishment.

Mac McCraw was on his way to a cocktail party with other officers when he saw his son.

Go to your room, he said. I’ll discipline you later.

But in a military town with schools full of military kids, word of how the young McCraw had stood up to the bullies had already spread to the cocktail party.

When the colonel came home that night, there would be no discipline. He was proud of his son.

And, Youngs said, the Jefferson kids never came back.

In Uvalde: The colonel becomes the critic

On May 27, three days after the shooting, McCraw stood before a throng of microphones near Robb Elementary School as reporters shouted questions at him. How did a teenager afford such expensive guns? What did the school police do? What would you say to the parents who are about to bury their children?

McCraw took the questions calmly, one by one.

Then it got personal.

“What is on your heart?” a reporter asked. “How are you doing? You're shaking the whole time you're up here."

McCraw turned away, shuffled some papers in his hands, breathed hard then turned back to the reporter.

“Yeah, thanks a lot,” he said, his voice shaking. “Forget how I’m doing. What about the parents of those children?”

In those first chaotic days after the shooting, when reporters from all over the world converged near Robb Elementary on Old Carrizo Road, nothing made sense. Not just the atrocity itself. Not the stories coming out of law enforcement.

Abbott praised officers’ “quick response” to the shooting, saying that officers “running toward gunfire” had saved lives. Then parents disputed that, saying they had to scream at police to enter the school.

Initial reports said the shooter had been confronted by a Uvalde school police officer outside the building and the two exchanged gunfire. That never happened.

Then cops said the shooter got in the school through a door propped open by a rock. That never happened.

And on it went for days until finally, McCraw did something few officers ever publicly do. He blamed other officers for botching the response.

The Uvalde school police department didn’t treat the scene like an active shooter incident, McCraw said. And he blamed the man he said should have been the incident commander, the man on the scene who should have been issuing orders and plotting a plan to take out the shooter: Arredondo. From that moment forward, Arredondo was the prime target of a nation’s rage.

"From the benefit of hindsight, where I'm sitting now, of course it was not the right decision,” McCraw said. “It was the wrong decision. Period."

Steve McCraw: Becoming the son his father saw

There was one other place where a young Steve McCraw and his father failed to see eye to eye.

McCraw was a wrestler. He had wrestled in California and was pretty good at it.

His father, the former football star, didn’t know what to think of wrestling. This was Texas. McCraw would play football.

He became a Burges Mustang.

“He was a very aggressive football player,” said Bill Birkhead, the team quarterback who remains friends with McCraw. “He played as hard as he could.”

But McCraw still wanted to wrestle. Finally, with some pushing, his father relented.

On Feb. 4, 1972, McCraw was a senior competing at the city wrestling tournament at Andress High School. His father wasn’t supposed to be there that day, but showed up after a meeting in his Army uniform.

He didn’t know anything about wrestling. But he sat in the bleachers with the other parents, cheering as his son quickly dispatched one of the competitors.

Then a trainer from another school saw Mac McCraw clutch his chest and fall to the floor.

Steve McCraw was still with the other wrestlers and his coaches were trying to block his view, shield him from what was happening in the stands.

Then someone told him. McCraw rushed to the stands and found his father already dead.

The teen said goodbye to the man who had tried to teach him to work hard, study, be respectful and consider a life of service.

Someone else might have sat out the rest of the tournament. McCraw knew that’s not what his father would have wanted.

“I knew that he’d want me to continue wrestling,” he said.

He pinned his next opponent in four minutes and 30 seconds.

After his father’s death, McCraw didn’t want to stay with his stepmother. He didn’t want to move back to California. So he lived in his red convertible Chevy Nova. Two weeks later, it was stolen.

The girls social club kept their “sweetheart” well fed. But he had nowhere to sleep besides the school locker room.

Fellow football player Mike Hernandez wasn’t about to let that stand.

Hernandez brought McCraw to the house one day and that was it. McCraw was home.

Lupe and Robert Hernandez already had six kids. Guadalupe worked in McCraw’s school cafeteria. Robert was a plant manager at a clothing manufacturer. There was so little space in the 1,100-square foot house, but they made room.

No matter. McCraw’s adopted family welcomed him in. They laughed at the mounds of cereal he would eat out of a mixing bowl. Guadalupe doted over him.

Isn’t that so cute? He’s eating so much. That’s so great.

Decades later, when Mike and Guadalupe died, their obituaries listed him as “brother” and “son.”

After graduating from Burges High School in 1972, the El Paso rabble-rouser was replaced by the man his father had pushed him to be.

“At the end of the day, I recognized that you can't go through life fighting,” he said.

McCraw joined the Army in El Paso and attended New Mexico Military Institute with his heart set on going to West Point. The next year he got in, he said, based on his improved SAT scores and athletic skills.

But when his little brother got in trouble with the law, McCraw pulled out of school to help him, he said. He ultimately took a football scholarship with West Texas State University in Canyon, now known as West Texas A&M University.

McCraw spent 1975 through 1979 earning his degree in political science and the two years after that getting a master's degree in psychology, sociology and criminal justice.

But in the meantime, he did something else, something few could imagine Wildman McCraw ever doing.

He became a cop.

In Uvalde: Finding 'systemic failures'

After the Uvalde shooting, McCraw commissioned the first official investigation.

The Advanced Law Enforcement Rapid Response Training (ALERRT) Center at Texas State University produced a 26-page report that targeted Arredondo for failing to take charge of the scene and aggressively target the attacker before he could kill more children.

The report includes a minute-by-minute timeline that runs several pages long, documenting the buildup of forces, which it describes as “including UPD, UCISD PD, Uvalde Sheriff's Office (USO), Fire Marshals, Constable Deputies, Southwest Texas Junior College Police Department (SWTJC PD), and the United States Border Patrol (BP).”

The timeline mentions only a single DPS trooper, who is described as hearing other officers discuss children in the classroom, and replying, “if there is then they just need to go in.”

It says nothing about what 90 other troopers were doing – or not doing – to save the children and teachers still in the room with the gunman.

The subsequent report from the Texas House committee would find “systemic failures and egregiously poor decision making.” Yet it, too, would make barely any mention of DPS presence during the timeline.

John Curnutt, assistant director at the ALERRT center, told USA TODAY that in the apparent absence of a declared commander, it apparently became implied. As more state and federal officers arrived, Curnutt said, Arredondo “should have said, ‘I need you to take command.’ Why didn’t that happen?”

But Stephen Owen, a professor of criminal justice at Radford University, said there is no clear doctrine on who becomes incident commander in such a situation. In general, he said, deference goes to the officer who has the most experience, training and primary jurisdiction. In a chaotic scenario with many cops and multiple jurisdictions, that may be unclear.

“The fact that a half hour into the shootings you’ve got all these officers standing in the hallway indicates it isn’t handled well,” he said. “When it doesn’t work, you have to ask the question: Should someone else take command?”

Owen said he did not immediately know of any case where a scene commander was ousted in such a way. It goes against the culture of law enforcement, and it can be pulled off only if the person taking command has people and a plan, he said.

Gutierrez, the state senator, had a front seat to the shifting narrative in those early days. He was in the first law enforcement briefing where Abbott came to the conclusion that officers had acted heroically. Gutierrez said he came to the same conclusion at first.

But his conclusions began to shift when McCraw began citing Arredondo’s missteps, assigning blame.

At first, he thought Abbott and McCraw were just looking for a scapegoat. But he quickly saw a deeper agenda – to deflect blame.

As videos emerged, Gutierrez noted a DPS officer in the hallway for a long time, talking on the phone, but doing nothing to get the shooter.

“That’s why I told people DPS was a failure in Uvalde,” Gutierrez said. “Who’s he on the phone with? Which supervisor?... Why didn’t they tell him to go in and get that guy?”

DPS, he said, “did not want to acknowledge their own failure.”

Steve McCraw: To the FBI and back home again

The first time Steve McCraw climbed behind the dashboard of a highway patrol cruiser, something just clicked.

There was so much autonomy, he said. So many decisions to make.

He spent six years at DPS starting in 1977, first as a patrol trooper, then as a narcotics investigator.

In that time, he saw a lot of drugs – meth, mostly – while working undercover with biker gangs in Texas. Mexican heroin was coming from mom and pop shops, he said. Meth was coming from larger labs.

McCraw wanted the big fish, the network. He wanted a shot at organized crime.

That, he thought, is how I can really help the United States. So he joined the FBI.

There, he found even more important decisions.

In the FBI, one man was revered as the undercover agent who helped take down some of the biggest players in the Bonanno crime family.

Joe Pistone. Better known to the world as Donnie Brasco, his undercover name, thanks to the movie starring Johnny Depp.

That’s what McCraw wanted – to take down the big guys doing the worst damage.

Over the years, he helped make cases against members of the Bonanno and Patriarca crime families for drugs and theft; targeted the Colombian and Mexican cartels; established drug intelligence groups; managed racketeering investigations.

His work took him across the country, Tucson, San Antonio, Los Angeles, Washington, D.C.

He kept climbing the ladder.

In 1999, after the Centennial Olympic Park bombing in Atlanta, McCraw was named head of the Southeast Bomb Task Force assigned to catch Eric Rudolph. It didn’t happen under his watch. But two years later, just after the 9/11 attacks, McCraw was named chief of the nation's Foreign Terrorist Tracking Task Force. Attorney General John Ashcroft introduced McCraw in a news conference that soon turned to the developing story of the moment: the postal anthrax attacks.

Back home, his friends proudly watched their football buddy rise.

“He’s our Captain America,” Birkhead said of his friend. “We all look up to Steve.”

In 2004, then-Gov. Rick Perry was looking for someone to head the state’s Department of Homeland Security, and McCraw was ready to come home to Texas.

A job running a state agency aligned McCraw with a new kind of boss. In his career as a lawman, he had worked within the operations of the state police and the FBI. In Texas, he was reporting directly to a politician.

He became only the second state Homeland Security director – the first, who he replaced, had been Jay Kimbrough, widely regarded as Perry’s “Mr. Fix-it” inside state government.

McCraw’s biggest task was also the most controversial: monitoring the Texas-Mexico border.

Perry instituted Operation Linebacker, an effort to fight border crime that allocated $10 million in federal grants to 16 border county sheriffs. An El Paso Times analysis later found the federal dollars intended to fight drugs and crime had instead been used mostly to target undocumented immigrants. It was the first of many state border efforts since then, under Perry and Abbott, spending billions of dollars to send troopers, gunboats and aircraft to communities along the Rio Grande.

McCraw came up with Operation Rio Grande, a central intelligence gathering network for border law enforcement, which was intended to allow quicker deployment of state resources to border hot spots.

He also established Perry’s web-camera border program, which installed cameras and let the public monitor for border security. (News reports at the time said the program, in its first year, installed 17 cameras and caught 11 criminals.)

As McCraw was confronting border issues, his old state agency home had fallen into chaos. The governor’s mansion had been torched by an arsonist, in a crime that remains unsolved today, and the security failures that had allowed it led to one DPS director’s exit.

The next director was soon accused of sexual harassment and also departed.

By 2009, at DPS, Perry needed a director to fight through the troubles of the state’s top law enforcement agency.

McCraw took the challenge.

In Uvalde: Where was DPS?

In Uvalde, as the memorials ended and the funerals passed, grief turned to rage.

By mid-July, the Austin American-Statesman obtained surveillance video that showed the shooter walking into the school and officers running away from early blasts.

Surveillance footage: Exclusive video shows officers' delayed response to mass shooting

Then, bodycam footage released by the city police department provided more detail of officers looking for keys and trying to persuade the shooter to give up his gun while children called 911 for help and the killer continued to sporadically fire his weapon.

Body cameras: 'Are we going in or we staying here?' Chaos, confusion on Uvalde police bodycams

And when the 77-page House report was released, families finally got a fuller picture of exactly what happened. The report blamed systemic failures and egregiously poor decision making; school officials who didn’t follow safety plans; and responding law officers who failed to follow their training for active-shooter situations and delayed confronting the gunman.

"They failed to prioritize saving the lives of innocent victims over their own safety," the report said of law officers.

While the report’s timeline still made little mention of DPS, it detailed the size of the response.

The number of Uvalde Consolidated Independent School District officers: five.

The number from the Department of Public Safety: 91.

In Uvalde, community outrage stayed mostly focused on the local police.

Arredondo, the schools police chief, had recently been elected to the city council. Residents protested in the downtown square, and he eventually resigned.

They swarmed to the school board meetings, shouting that Arredondo needed to be fired from his job as schools police chief.

But even as the community aimed its ire at its local law enforcement, DPS started coming up.

At one school board meeting, where DPS troopers stood guard, a resident started yelling at them.

Were you there? What were you doing?

The videos showed exactly what some of those troopers were doing.

There were some in tactical gear, some gathered at the hallway corner, some asking with a note of incredulity if it was really true that children were inside the classroom. There were some searching the school, evacuating children.

One was the special agent who had been mentioned in the early reports. He found one child hiding in a bathroom stall, and even poked his badge under the stall door to reassure the boy it was safe to come out.

But there were other troopers.

One was in the courtyard. As the first city police officers arrived, she was already at the door to the building. The local police lined up and passed her, as she remained, waiting alone by the exterior door.

Another was on scene from the early minutes of the local police response, because he drove there with a police officer whose wife, a teacher, was calling because she had been shot.

DPS has not confirmed if any of those troopers seen on video are among the seven it has referred for investigation.

Uvalde resident Kim Hammond, who has been pushing to hold school district and city officials accountable, said that the ever-changing information made people focus mainly on what was right in front of them: Arredondo didn’t protect their children.

But after reading recent news articles questioning the state agency’s actions, Hammond said, “I see now that DPS should have stepped in … kicked all the locals out and took over. Short-sighted we may be, but it’s all coming out now.”

Steve McCraw: DPS’ tough situations

Today, McCraw has three adult children. He’s married to a woman he met while they both worked for the FBI. At 68, he’s back at the agency where his career began.

But he’s decades removed from that trooper who first found his calling behind the wheel of a west Texas patrol car.

While McCraw brought more than a decade of stability to the director’s seat at DPS, he didn’t see the end of controversy at the 11,000-person agency.

Thanks to Attorney General Paxton and the Secretary of State for uncovering and investigating this illegal vote registration. I support prosecution where appropriate. The State will work on legislation to safeguard against these illegal practices. #txlege #tcot https://t.co/UwtyXijVwK

— Greg Abbott (@GregAbbott_TX) January 25, 2019

When Texas attempted to review its voter rolls in 2019, DPS handed over a list of suspected non-citizens. But the agency failed to clarify that its list of nearly 100,000 names included many who had actually proved their citizenship – causing officials to wrongly question the eligibility of thousands of people. Abbott at first touted the election review as proof of election fraud, but later had to rebuke DPS. McCraw took responsibility.

When 28-year-old Sandra Bland, a Black woman, was violently arrested in 2015 by a DPS trooper in Waller County for a minor traffic infraction, she later died by suicide in jail. McCraw fired the officer, who also faced a perjury charge that was dismissed in exchange for a promise never to seek work in law enforcement again.

But the agency came under renewed fire in 2019, when video of the traffic stop – shot by Bland herself, on her cell phone – emerged publicly. Bland’s family said the video disproved the officer’s original claim that he had feared for his safety; they questioned why DPS had not released the video years earlier. The agency said that it had, in fact, released the video in 2015 and that is was specifically mentioned in a Ranger investigation into the incident.

Perhaps McCraw's most-blasted effort remains the one along the U.S.-Mexico border.

In 2021, the state kicked off Operation Lone Star, a more than $2 billion effort to pump up security along the border with manpower from DPS and the National Guard. Abbott promoted the effort as a way to help catch Mexican cartels and smugglers, but advocates deem the effort a disaster, saying civil rights violations are rampant, legal immigrants are being detained and National Guard soldiers have been treated poorly.

The U.S. Department of Justice is currently investigating Operation Lone Star for alleged civil rights violations, according to state records obtained by ProPublica and The Texas Tribune.

The border remains a political priority of the governor, who, in a statement to USA TODAY, credited McCraw with “implementing innovative strategies to combat President Biden’s historic border crisis.”

McCraw knows that his job, no matter how he does it, comes with criticism.

Internally, its own employees have repeatedly filed lawsuits and complaints, alleging corruption, harassment, discrimination or other problems.

Former DPS special agent Darren Lubbe was among those people.

Lubbe had been a member of the Texas Rangers Special Operations Unit, and in 2013 was one of three officers to receive a director’s citation for his response to the West, Texas, fertilizer plant explosion.

Later, though, he became a plaintiff, alleging in a 2018 lawsuit that “under Director Steven McCraw, a ‘good old boy’ culture of cronyism and outright corruption has flourished at the Texas Department of Public Safety.”

The civil complaint – which was dismissed for procedural reasons in July and is now being appealed – enumerated numerous other cases where, it alleged, unlawful DPS conduct allegedly got whitewashed.

“When they can no longer cover up misconduct by a senior officer, the investigation is delayed and the senior officer is allowed to retire quietly,” the suit stated.

In response to that lawsuit, attorneys for DPS and McCraw claimed Lubbe – once portrayed as a police hero – had become a derelict officer who habitually played fast and loose with rules and authority, imagined private feuds with colleagues and unilaterally destroyed his credibility.

McCraw says he doesn’t worry about things like that. He says he has great communication with most of his people.

“There's going to be a certain percentage that aren't going to be happy,” he said.

Then there are those outside of the agency, some of whom blast McCraw not just for his enforcement efforts but for how closely the agency’s efforts align with Abbott’s political priorities, especially as a tough-on-immigration candidate.

The colonel says he’s no puppet of the governor.

“He has an expectation that I tell him what I think,” McCraw says, “Not what he wants to hear.”

But McCraw will acknowledge: “He got us into doing some things we would never have done before.”

He’s talking not about the border, but another operation, hundreds of miles north.

Over the past six years, Abbott and McCraw have repeatedly deployed DPS troopers to Dallas to combat violent crime spikes while helping a police department that lost hundreds of officers after a city pension fund collapsed.

In each case, the campaigns were welcomed by Dallas' mayor, police chief and communities plagued with gang crimes and spiking violence.

However, the 2019 operation prompted a backlash after troopers on street patrol allegedly targeted communities of color with traffic offenses and petty crimes.

DPS claimed more than 1,000 arrests over several months, and McCraw said the public overwhelmingly appreciated state police assistance. The critics, he added at the time, were mostly either those who got arrested or their families.

Two years later, DPS officers again were sent to help Dallas police. But, this time, they wore plain clothes and worked on criminal investigations, rather than street patrols.

McCraw acknowledged it was controversial to run state patrol cars – “black and whites” – on city streets. “But you know, if there's no murders while you're there, if the people feel safe, they love you while you're there,” McCraw told USA TODAY. “Maybe not the activists, but the people.”

Asked to think back through all the difficulties of law enforcement – the slain officers, the employee complaints, the challenging investigations – McCraw does not hesitate to specify which cases hurt the most.

“The worst cases are cases against children,” he says. “It’s human nature to be able to protect our most innocent. … So those are the toughest cases.”

In Uvalde: Spotlight continues to creep toward DPS

In McCraw’s telling, the sequence of events May 24 goes like this.

In his Austin office, he got a call about the shooting. He ordered Victor Escalon – DPS regional director for South Texas – to head to the scene.

DPS was digging up information any way they could, he said: calls to law enforcement, contact with Escalon, social media.

But they still didn’t know what was going on, McCraw told USA TODAY.

“We never feel confident that we will have a handle on it until we get people on the ground and find out what’s going,” he said.

McCraw told USA TODAY that the agency’s first captain wasn’t on scene until 12:25 p.m., almost an hour into the standoff.

While the internal DPS inquiry continues, McCraw told CNN last week that he had made a “command decision” that Escalon had done everything he could.

The day after the shooting, McCraw sat onstage for the governor’s first news conference and did not contradict Abbott when he extolled law enforcement for a supposedly quick response.

Two days later, he spoke again, this time with the results of an initial review. The totality of the failure was becoming clear, and on that same day, Arredondo became the face of that failure.

The Uvalde school board finally fired Arredondo on Aug. 24, exactly three months after the shooting. As that decision came down, the former police chief let loose on the man he blamed for much of his troubles: McCraw.

In a press release issued the day he was fired, Arredondo insisted he had done everything he could to save the children and employees of Robb Elementary. The only person to blame was the shooter, he said.

“But finally,” the statement reads, “Chief Arredondo hopes at least those who are willing to listen, understand that he is, and has been, from the time McCraw unfairly singled him out, being forced into the role of the ‘fall guy,’ ‘the sacrificial lamb,’ whichever term preferred; and, this once again demonstrates that no good deed goes unpunished.”

As Arredondo lashed out, McCraw had no reply.

In July, McCraw sent an internal e-mail to his staff, issuing directions that addressed the failures inside Robb Elementary.

“When a subject fires a weapon at a school he remains an active shooter until he is neutralized and is not to be treated as a ‘barricaded subject,’” he wrote.

But he also issued a new directive that, in Gutierrez’s view, speaks volumes about the DPS response.

“We will provide proper training and guidelines for recognizing and overcoming poor command decisions at an active shooter scene,” McCraw wrote.

Gutierrez sees the e-mail as confirming what he has believed all along.

“Steve McCraw doesn’t want it to be an admission of their negligence,” he said, “but it absolutely is.”

McCraw remains the narrator of his own story, one of bashing bullies and chasing the cartels. But he is no longer the official narrator of Uvalde.

For now, the inspector general will investigate his officers. Gutierrez will push for answers. DPS will keep facing questions.

Perhaps only at the end of all those questions will it become clear who has truly been protected.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: How Texas DPS chief Steve McCraw became the narrator of Uvalde