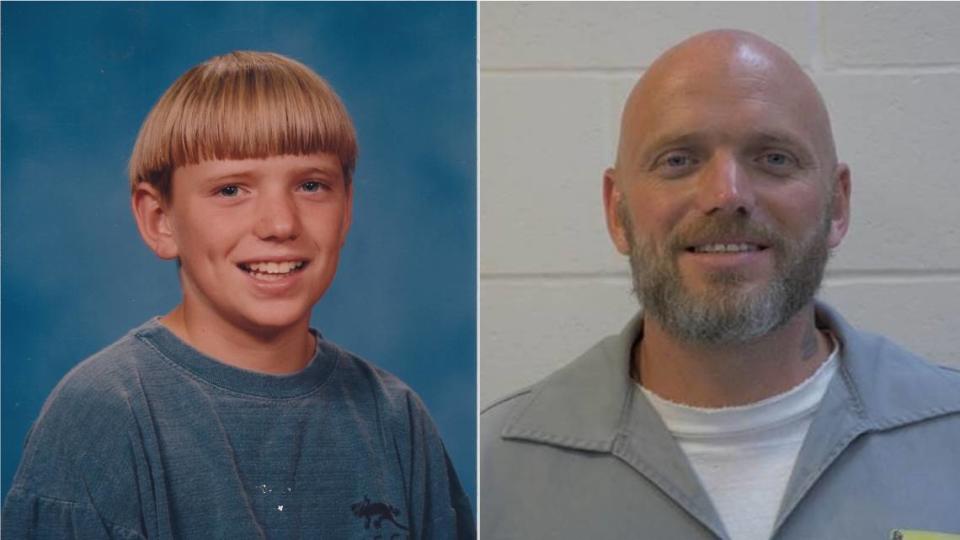

‘A terrible mistake’: 2nd juror now says Missouri prisoner is innocent in 1998 murder

A juror who voted to convict a Missouri man of killing his mother more than 20 years ago now believes he is innocent, according to a petition filed late Wednesday in the state Supreme Court. She is the second juror to publicly change course.

Michael Politte, 14 at the time, quickly became the prime suspect in his mother’s 1998 murder after he found her body burning on the floor of their Hopewell home in eastern Missouri, his lawyers say. He was convicted of second-degree murder four years later and sentenced to life in prison.

Now 37, Politte and his sisters maintain he was wrongly convicted. So do two jurors who voted to find him guilty, including one who recently contacted his attorneys, according to the Midwest Innocence Project and the MacArthur Justice Center.

In an affidavit last week, Linda Dickerson-Bell, of Bonne Terre, said she always had doubts about Politte’s guilt, but that she was pressured to vote to convict him by other jurors, including one who said he wanted to “hang the kid.”

“If I had known then what I know now, I would not have convicted,” Dickerson-Bell said, adding that the verdict has weighed on her heavily. “I now believe Michael is innocent.”

In their petition before the state’s highest court, Politte’s attorneys argued that he was convicted because of a biased investigation, faulty science and an incompetent new public defender at trial. They hope it leads to his exoneration and release.

Josh Hedgecorth, the current prosecutor in Washington County, where Politte was prosecuted, said he had no comment.

A spokesman for Missouri Attorney General Eric Schmitt declined comment.

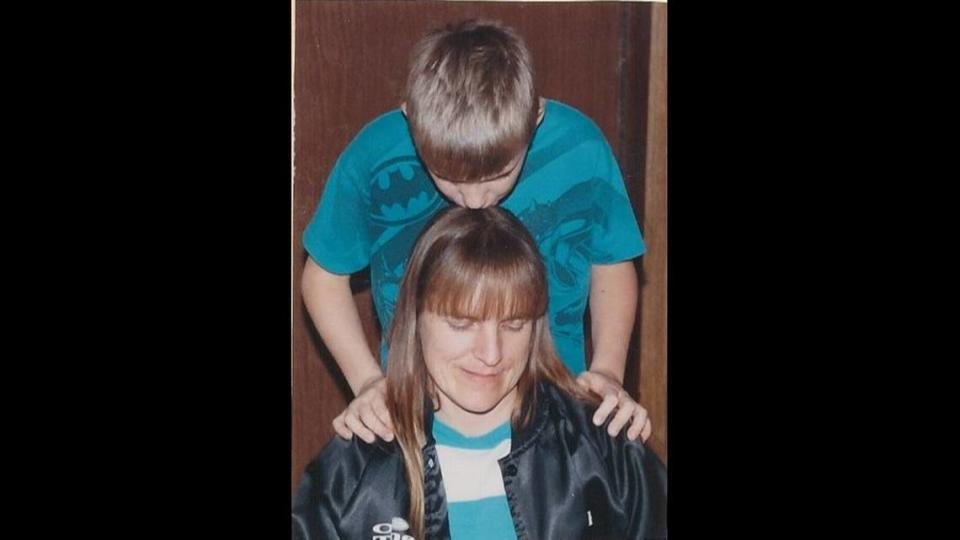

On Dec. 5, 1998, Politte and a friend awoke to smoke at his mother’s mobile home, according to his petition. He told law enforcement he found the burning body of his mother, Rita, in her bedroom. She had also suffered blunt force trauma to her head.

Investigators quickly decided the fire was started with gasoline, and law enforcement immediately zeroed in on Politte as a suspect. But no blood or other injuries were found on him, the petition alleges. Investigators also misinterpreted his trauma and stress as indicators of guilt, his lawyers said.

Law enforcement did not investigate other viable suspects, including Politte’s father — recently divorced from his mother — who had been ordered to pay a “significant” financial settlement the week before she died, the petition claims. Witnesses also said a cousin of Politte’s father was seen around the home shortly after the fire. A murder weapon was never found.

Politte was arrested two days after his mother’s killing. While being handcuffed, he “frantically asked the officers to take his fingerprints because someone was trying to frame him,” his lawyers wrote.

At trial, the case against Politte rested largely on testimony from fire investigators who said the blaze was started by an accelerant and that he had gas on his shoes — the only physical evidence linking him to the killing.

Those findings were based on fire investigation techniques that have since been discredited, and the state has conceded in the intervening years that Politte did not have gas on his shoes, according to his petition. The compounds were simply ones “commonly used in the shoe manufacturing process,” Politte’s lawyers said, citing an analysis by one of the country’s top experts.

Even before the 2002 trial, the crime lab admitted it knew the testing methods it used on Politte’s shoes produced unreliable evidence, said Megan Crane, one of his attorneys. The lab adopted new methods because of it in the late 1990s.

“Yet they didn’t retest his evidence,” Crane told The Star.

Prosecutors at trial also claimed Politte, while attempting suicide at a juvenile detention center, uttered, “I am have not cared since Dec. 5, that’s when I killed my mom.” But his attorneys contend he said “when they” killed his mom.

“What he actually said has been hotly disputed ever since,” they wrote.

Politte’s petition includes an affidavit from Tammy Nash, who was a Washington County deputy sheriff who helped investigate the killing. She said investigators were split on whether Politte was guilty. Her doubts grew as she got to know him.

Nash remembers Politte crying frequently and saying, “if my mam was here, she would tell them I would never hurt her and I did not do this,” according to her affidavit. Nash believes Politte is innocent.

The latest juror to come forward, Dickerson-Bell, saw on Facebook that Politte’s attorneys filed a petition in an appeals court in August. She sent a message to his lawyers that said, “What can I do to help make this right?”

Now head of St. Francois County’s Habitat for Humanity, Dickerson-Bell said she previously hesitated to watch an MTV documentary series that featured Politte’s case, but wondered if it would put her “mind at peace” about the verdict.

Instead, she learned there was not gasoline on Politte’s shoes, which she called the “nail in the coffin” for her.

“After learning about the new evidence, my guilt has only grown,” she wrote. “I now firmly believe ... that we made a terrible mistake.”

Jurors thought of Politte as “Burny” because that was how he was referred to at trial, Dickerson-Bell’s affidavit stated. The prosecutor also told jurors he liked to burn things. She now knows his nickname was “Bernie,” which stemmed from his middle name.

Dickerson-Bell was not the only hold-out juror at the time.

In a 2017 affidavit, another juror, Jonathan Peterson, said he did not think “justice was served” when Politte was convicted. He did not believe Politte was innocent, but he also did not think the teenager could have killed his mother by himself. While he was “unsure” Politte “did it,” he voted to convict after he felt pressured by the judge to make a decision, according to his affidavit.

But the jury foreman, Victor Thomas, now believes Politte is innocent and “should be freed to correct this wrong.” He and other jurors would not have convicted the boy had they know about the victim’s divorce and other evidence, he said in a 2017 affidavit.

“The jury never heard evidence about any other possible suspects,” he recalled.

Crane, co-director of the MacArthur Justice Center’s Missouri office, described it as “striking” when more than one juror comes forward to say they got the verdict wrong. But she said it’s not surprising given that the “only evidence” against Politte was undeniably false.

”The state’s prioritization of finality over fairness is premised on protecting the jury’s verdict,” Crane said. “That goes out the window when the jurors themselves believe he is innocent and want their verdict reversed.”

Politte remains imprisoned at the Jefferson City Correctional Center.

In a recent interview with St. Louis Public Radio, Politte said prosecutors offered him a 15-year prison sentence if he agreed to plead guilty to voluntary manslaughter. He would have been released more than a decade ago had he taken it, he said.

“I didn’t murder my mother,” he told the radio station.

Ricky Kidd, a Kansas City man who spent 23 years in prison for a double murder he did not commit, told The Star he found Politte to be “authentic” when he told him he was innocent.

“It was a problem for me to hear everybody say they innocent because ... the voices of those who were truly innocent were drowned out,” Kidd, who was freed in 2019, said Wednesday. “But I always had a sense that when Michael said he was innocent, I believed him.”

Missouri has recently been in the national spotlight for two high-profile cases that local prosecutors say are wrongful convictions.

In Kansas City, Jackson County Prosecutor Jean Peters Baker’s office determined Kevin Strickland, 62, has spent more than 40 years in prison for a triple murder he did not commit. A hearing during which she will argue he is innocent is set for Nov. 8.

On the other side of the state, St. Louis Circuit Attorney Kim Gardner’s office concluded Lamar Johnson, 47, has spent the past 26 years in prison for a 1994 murder he did not commit. Johnson also remains behind bars.

Baker and Gardner have faced opposition from the Missouri Attorney General’s Office in their efforts to free the men.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.