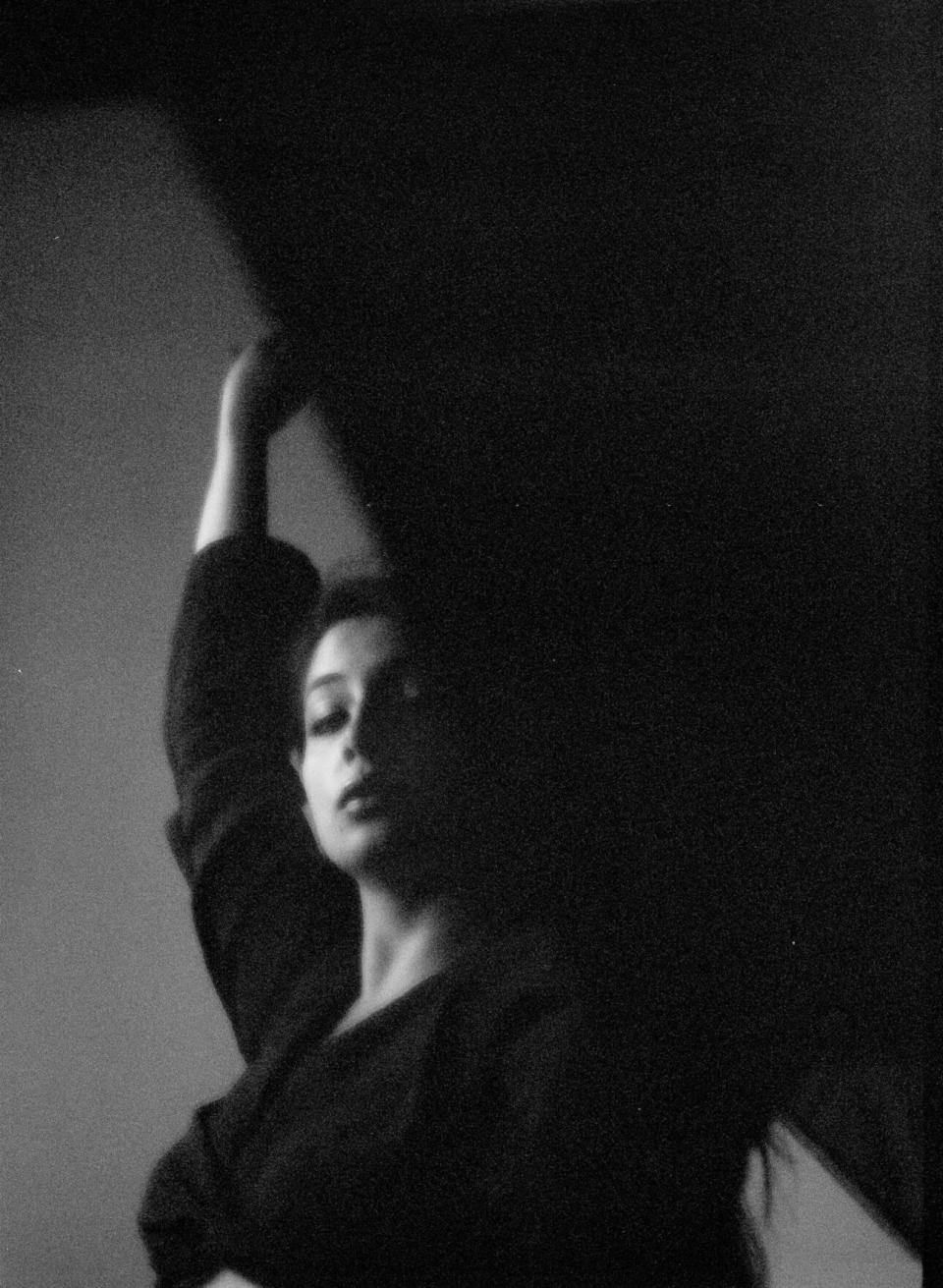

Tell Us a Story, Sheherazaad

I meet Sheherazaad in a room within the Brooklyn Conservatory of Music that feels like a dollhouse. The steeply slanted roof makes the space seem small; the chairs are just a foot above the ground, as if made for children or toys; and the elevator up smells vaguely like crayons. But these particularities evaporate as Sheherazaad starts singing.

Almost as soon as I enter the room, she asks if she can do a vocal warmup ahead of our interview. For the next 10 minutes, she plays a droning tanpura on her phone, paces the room, unfurls her hip-length black hair from a bun, and cascades her voice through microtonal scales and an inky take on the Gayatri Mantra, a Hindu chant that praises the power of the sun.

Then she wraps up, sits down, and casually asks me, “So, how are you?” The ordinariness of the question, contrasted so starkly to the ethereal atmosphere she just created, leaves me momentarily speechless.

Sheherazaad’s ability to curate a dramatic moment shouldn’t be surprising. As she whispers with joking guilt a few times during our conversation—she is also an actress, after all. Because of that training, she’s prone to think about storytelling, plot, and character development in everything she does, from the tone she sets for our interview to the narrative arc of her forthcoming album, Qasr.

The project, which merges folk, experimental music, and Hindu and Urdu poetry, is dense, mythological, and emotionally fraught. Sheherazaad alternatively croons, whispers, and wails in Hindi as she tells the stories of five fictional women grappling with debilitating guilt, weariness, and mental illness. On lead single “Mashoor,” the protagonist tangos with a golden acoustic guitar line as she laments everything she’s lost in the pursuit of fame. And on “Koshish,” she alternates between sighing and twirling her crystalline falsetto over a wash of surf-rock synth and oud while looking back on her youth with longing and regret.

This anxious, operatic music could soundtrack Lady Macbeth attempting to scrub her hands clean or Scheherazade, her namesake character from Middle Eastern epic collection of folktales One Thousand and One Nights, frantically telling story after story to a bloodthirsty king to keep him from killing her. As Sheherazaad puts it, “The speakers on the album have ascended to a place of arrival and are looking back on a path littered with sin and violence and the unforgivable.” The women of these songs are so compelling and singular because they present in plain sight the impulses and fears—selfish ambition, unquenchable yearning—that most people spend their lives trying to deny or hide.

Despite the heaviness of the work and the otherworldliness of the vocal performance she offered within minutes of meeting, Sheherazaad is exceedingly warm and down to earth in person. After asking me how I’m doing, she asks if I’ve eaten and then insists immediately on sharing half of everything she has with her: a banana, an oat pastry, and even her cup of chai, which she describes apologetically as tepid. “What languages do you speak?” she asks as I half-heartedly protest the food. “Saval nahi hai. [There’s no question]. Please do eat.” She decorates our conversation with Hindi phrases and tells me of the kinship she feels with other South Asian-Americans, whether they’re fellow musicians who are “playing with lineage and accessing lost worlds” or me as an interviewer. The women in her songs may feel isolated and particular, but for Sheherazaad, connection flows like red wine.

Sheherazaad grew up immersed in music. Her parents, whom she describes as “Berkeley hippies from the ‘70s,” met in a still-active Bollywood cover band for which her mother was the lead singer and her father was a pianist. Her grandmother was a concert producer for major Indian classical musicians like sitarist Ravi Shankar and tabla player Zakir Hussain. She was one of the first people to introduce Indian classical music to the West Coast some 40 years ago.

Sheherazaad started training in Western music at the age of six and grew up doing high school choir, opera, and musical theater. After graduating from New York University, where she majored in global education studies, she moved back to the Bay Area to immerse herself in Indian classical music with a guru she met through her grandmother. She also started reading Hindi, Urdu, and Arabic texts, and letting beautiful-sounding words like “maqtal” or “mashoor” jump out at her on the page and inform the lyrical direction of her songs. In 2020, Sheherazaad released her debut project, Khwaabistan, which caught the ear of Pakistani-American composer Arooj Aftab, who offered to produce whatever she made next.

Aftab is a fitting collaborator for Sheherazaad. Most obviously, the two artists have deep knowledge of overlapping diasporic neo-classical musical traditions and the ability to pull from and merge them into completely new sounds without ever seeming gestural or trite. They also both exhibit what Aftab describes as “the guts to cut 90% of the instrumentation in order to hear one phrase and let the music really sing.” This patience and restraint allows their songs to reveal deep oceans of emotion with the ease of a summer breeze fluttering ripples across a pond.

“The music that I get involved with needs to feel like something you’ve never heard before. It’s high art. It has to be special and surprising and has to take you on a journey,” Aftab says about her desire to work with Sheherazaad. “[The demos she sent me] were beautiful: They had structure, depth and meaning to them, excellent arrangements, and there was a concept to the project. I felt like we could build them out to take it to the next level. She could have taken it there herself, but I was like, ‘I want to be along for the ride.’ Sometimes an artist really needs to be an artist, and they should have someone who shares the vision say, ‘Let me take the macro, big picture part off your plate.’”

The promise of Aftab’s involvement pushed Sheherazaad to finish the songs on Qasr. The album was written between Varanasi, India and San Francisco during a time of societal and personal strife. It was peak COVID and Trump era, and Sheherazaad was dealing with estrangement from her family and the death of her grandfather. “I shifted into a studio in the Bay Area that I was kind of squatting in,” she says. “It was a commercial building but they gave me really cheap rent because of COVID. I set up my studio and lived there. There was no bathroom or shower, so I would go to the gym. It was pagal [crazy]. There was nothing normal or understandable about it.”

On “Dhund Lo Mujhe,” a swirling, baroque string arrangement punctuates Sheherazaad’s staccato delivery as her character’s mind races to piece together various absurdist images: a female cow’s fear, a cupboard filled with the moon, a promise ruptured. The song was written while Sheherazaad was in Varanasi, known as the city of death, to be near her grandfather in his last days. “I was feeling the confusion of having just traveled there and being between places and worlds,” she says. “The images in the song are supposed to be bizarre, dystopic, and surrealist phrases that don’t make sense.”

Throughout the project, mental illness becomes an allegory for the confusion that diasporic people feel due to this sustained sense of placelessness. “The characters of all of the songs are straddling different irreconcilable worlds,” Sheherazaad says. “It creates a cognitive dissonance. The only natural state to resort to is madness.” In particular, Sheherazaad wanted to focus on mentally ill women because they’re usually overlooked in the South Asian musical imagination. “[Female characters] are often puppets for what men want to say,” she tells me. “But women are unreliable sometimes. We’re weird and gross and awkward. Why not represent all of those dimensions and not be cute, wholesome puppets?”

While composing, she leaned into dramatic orchestral instrumentation like strings and ornate, classical guitar, and consciously eschewed the flowery Hindi and Urdu poetry that reminded her of male ego. “Some of my grammar or pronunciation will be off as a way of paying homage to how nomadic people enunciate,” she says.” I used to be very embarrassed about how I composed in Hindi, but now I’m like, ‘Maybe there’s something powerful about the simplicity of language.’ Hindi and Urdu poetry has always seemed very masculine to me. There’s this idea that you have to be complicated to say something of importance, but I find that in the simplicity and accessibility lies the profundity.”

Diasporic placelessness is generally defined by a sense of absence, a feeling of not belonging anywhere. But Sheherazaad has recently started capitalizing the I and B in “in between,” to try to think of it as a space she explicitly occupies. This mindset defines Qasr, which builds monuments to ignored and overlooked characters, modes of speech, and sounds, and makes a case for the margins as spaces of insight and synthesis. Sheherazaad leans into her mispronunciations. She celebrates rather than laments her distance from Hindi, as it allows her to see ordinary words as sites of beauty. And she uses her positioning between cultures to imagine and synthesize entirely new sounds like West Coast surf rock paired with the oud or Hindi poetry punctuated with American folk sounds.

Similarly, her lyrics humanize characters whose negative emotions would likely cause men to dismiss them. But the women in Qasr are not lacking insight about the world. Rather, they are burdened by all that they know: that the pursuit of fame and legacy often requires selfishness, that pride can blind you from your shortcomings, that love you’ve been promised forever can evaporate overnight. They are sources of wisdom, and their stories are cautionary tales.

Sheherazaad is intent on being known and on making the women she represents in her music known too. Her tool for doing so is the music she makes and the stories she tells through it—not just the official songs she releases but her daily practice of singing, which she sees as a spiritual endeavor. During our two and a half hours together, she literally cannot stop the music from pouring out of her.

She asks if she can put on a playlist in the background while we speak to help her think. When we change rooms half way through the interview, she immediately sits down at the new piano and plays an entire piece by Yann Tiersen, the composer behind Amelie’s iconic score. Eventually, she performs “Khatam” too. And, after our interview, I watch her rehearse bits of “Mashoor” with her bandmates. At one point, I’m taking notes and am jolted to attention when I hear my name whispered in the lyrics amid a sawing cello and thumping percussion.

“We like to add our names into the song,” she tells me with a smile, as she seamlessly works me into the fabric of her world.

To see our running list of the top 100 greatest rock stars of all time, click here.