How Ted Nugent accidentally destroyed his first Gibson Byrdland

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

16-year-old Ted Nugent was on top of the world. In 1965, his band, the Lourds, had won the Michigan Battle of the Bands, beating out 60 other Detroit-area combos. To seal their win, Nugent jumped on the judges’ table to play his guitar solo. As the winning band, the Lourds got to open for the Supremes and the Beau Brummels at Detroit’s Cobo Hall on June 13, 1965. They played a medley of High Heel Sneakers, Walking the Dog and Shake Your Tail Feather.”

“I was smokin’ in Detroit,” Nugent says today. “The Lourds were just kickin’ ass... We were getting ready to open up some shows for the Stones.”

Unbeknownst to Nugent, the Lourds were about to end abruptly.

In the fall of 1965, H.K. Porter Co. transferred Nugent’s dad to Chicago for work. “It was horrible,” Nugent says. “I didn’t want to go.” But despite young Ted’s protests, Warren and Marion Nugent and their four children – Ted, his brothers Jeffrey and John and his sister Kathy – moved from Redford Township in suburban Detroit to Hoffman Estates, a small suburb outside of Chicago.

Nugent wasted no time forming a new band, the Amboy Dukes, who began playing at The Cellar in the Chicago suburb of Arlington Heights, among other venues. The Amboy Dukes quickly became one of the hottest bands on the Chicago scene, competing with the Shadows of Knight and the Ides of March for the mantle of the city’s top band.

The call of the Byrdland

Prior to moving to Chicago, Ted had the opportunity to see Billy Lee & the Rivieras at the Walled Lake Casino near Milford, Michigan. Led by vocalist Mitch Ryder and guitarist Jimmy McCarty, the Rivieras were an early incarnation of Mitch Ryder and the Detroit Wheels. McCarty played a Gibson Byrdland.

“Oh boy! How I love revisiting these spine-tingling memories of my Motor City guitar youth,” Nugent says. “The Lourds opened up for Billy Lee and the Rivieras, Gene Pitney and Martha and the Vandellas at the Walled Lake Casino outside Detroit in 1964. And there was Jimmy with a gorgeous Gibson Byrdland plugged into a black[-panel] Fender Twin Reverb, sounding like a dozen fire-breathing guitars with the most wonderful, widespread, full, rich, dynamic tone I could have ever imagined.

“At the time, I was playing a white Fender Duo-Sonic through a beige Fender Bandmaster and had a pretty cool sound myself, but the Byrdland was love at first sight/sound.”

“It was a sunburst,” McCarty says today. “It had like a three-quarter scale neck. I loved the short-scale neck thing at the time, but it was mainly the humbuckers – that was the first guitar that introduced me to humbucking pickups. Plug a humbucker into an old vintage Fender amp and I’m basically home.

“The Byrdland is a beautiful instrument. I also love the fact that it wasn’t the full hollowbody, like an L5 or a Super 400; it was a slimmer hollowbody, so it was more comfortable for me. I think we used that for pretty much the remainder of the Mitch Ryder/Detroit Wheels stuff.”

Suffice to say, Nugent wanted a Gibson Byrdland. However, it would not be until his family’s move to Chicago that Ted’s dreams of owning a Byrdland would be realized.

“Moving to the Chicago suburbs in 1965 and starting the Amboy Dukes, I got an Epiphone Casino and was really happy with it,” Nugent says. But, despite the Casino’s popularity in the hands of the Beatles, Stones and Kinks, Nugent had his sights set well beyond his current guitar.

“When I heard of a blonde Byrdland at the Roselle School of Music down the road, I got there as fast as I could. Eight hundred dollars may as well have been a million dollars, but the fine gentleman – Mr. Lyle Gillman – had faith in young Nuge and let me trade my Casino and $100 for her and make monthly payments of $100. Good Lord, the sonic adventure I was on!”

The Amboy Dukes make their move

After he graduated from high school in 1967, Nugent moved back to Detroit, bringing his Amboy Dukes bandmates and ’65 Byrdland with him. The Dukes signed with Detroit’s Mainstream Records and released their debut album, The Amboy Dukes, which featured their cover of the blues standard Baby Please Don’t Go. The album was purportedly recorded in one night on a four-track recorder.

In 1968, they released their best-known album, Journey to the Center of the Mind. Nugent’s original Byrdland delivers its trademark sounds throughout. The album’s psychedelic title cut reached Number 16 on the Billboard charts. The album also featured the tour de force Flight of the Byrd – Nugent’s ode to his beloved Byrdland – along with the sweet instrumental Scottish Tea.

Detroit Rock & Roll Revival

In the late ’60s, outdoor pop and rock festivals began springing up around the U.S., and Detroit was no exception. In 1969, the First Annual Detroit Rock & Roll Revival festival took place Memorial Day weekend at the Michigan State Fairgrounds, just outside the Motor City. With 35 bands appearing over two days, this was one of Michigan’s biggest rock festivals.

The festival was produced by Russ Gibb, who ran Detroit’s Grande Ballroom, home to the MC5, the Stooges, James Gang and 20-year-old Ted Nugent’s Amboy Dukes. To ensure a big turnout at the festival, Gibb wisely shut down the Ballroom for the weekend. While the actual attendance is unknown, the festival is speculated to have drawn at least 25,000 to 30,000 concert-goers over the weekend.

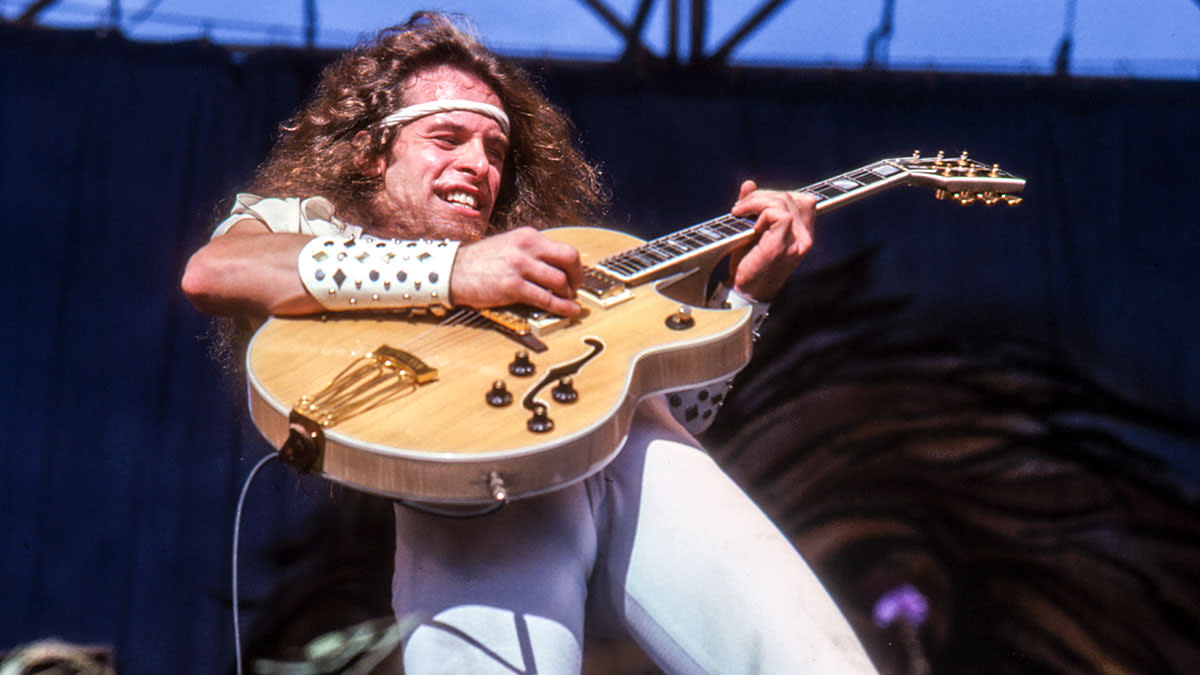

Rain showers dampened Saturday’s performances. At one point, the Amboy Dukes led a “Fuck the rain!” chant. However, as the Amboy Dukes closed out their set, tragedy struck Nugent and his treasured Byrdland.

“You may have noticed I get rather uppity when unleashing my beloved guitar music, and young Ted was not well versed in the controlled discipline realm when it came to exploring athletic acrobatics as the music drove me wild,” Nugent says.

“I get so damn possessed by the music that I find myself leaping from amp tower to amp tower, to drum riser and back and forth, here, there and everywhere on stage.

I must admit, it looked and sounded phenomenal, but the poor girl was crushed to smithereens as I climbed out of the pile... I was totally heartbroken

“At the Detroit festival I was wearing a long-fringed white jumpsuit, and as we crescendoed for the umpteenth time that day, I let the mighty Byrdland feed back ferociously against my Fender amp wall, bowing down to the howling beast, and backed off to do my end-of-set flying leap over the amps, when for some stupid reason, my fringe snagged on something in midair and I crashed headlong into a Twin and the whole wall of amps collapsed onto my beautiful blonde Byrdland!

“I must admit, it looked and sounded phenomenal, but the poor girl was crushed to smithereens as I climbed out of the pile. I’m sure I made it part of the show, but as the adrenaline subsided, I was totally heartbroken as I gathered the shards of spruce and Gibson shrapnel into a box.

“I took the box of assorted pieces to master luthier Dan Erlewine, and he told me there was little hope of fully restoring her, but he did the best he could do. Tragically, she never was really playable again, dammit!”

Erlewine recalls the project: “I saw and heard Ted play pretty early on as a ‘new guitar-slinger’ in town, and the word was out on him. I heard he played a Byrdland, and that intrigued me because he’s the only rock player I’d ever known to play one; I loved Byrdlands and had wanted one for some years – still do.

“Back in those days in Ann Arbor, Michigan, Gibson player/reps would come to Grinnell’s Music – a Michigan chain music store that sold Gibsons – and demo some of their finest guitars.

“One was a natural Byrdland just like Ted’s, and we got to play it and hold it when the demo was over. Otherwise, the Gibsons were in a glass case that was locked and had a sign that said, ‘Do not touch – you break it, you bought it.’

Where there were missing pieces, I used both clear and amber ‘stick lacquer’ to melt into the empty spots and then level and polish them into the existing finish

“I cleaned and glued the large open split areas and long cracks with Titebond aliphatic-resin glue. There were many small chips of wood free from the guitar with finish clinging to them that I glued in place. However, where there were missing pieces, I used both clear and amber ‘stick lacquer’ to melt into the empty spots and then level and polish them into the existing finish.

“Frankly, the repairs were done so long ago that I can’t remember much more than days of slowly patching the areas. I’d love to see the guitar in person, as I’m sure a lot would come back to me. I do know I repaired that guitar in my basement shop outside Ann Arbor.”

“I did my best for Ted; if the photos of the Byrdland shown here are of his first Byrdland (and I think they are), it looks better than I remember it. I can’t believe I could have done it that well at such a young age. It was shattered – just like Ted said!”

The Byrdland’s hollowbody spruce feedback threshold forces my hands to work in a certain way to milk a delivery of percussiveness, blaring, sustain, staccato and feedback

Nugent got the repaired Byrdland back in late 1969 and began using it again onstage with the Amboy Dukes. “I tried, but [I] chose against using my original baby on any future recordings or gigs due to its condition,” Nugent says. “Dan did a great job, but she was never the same.”

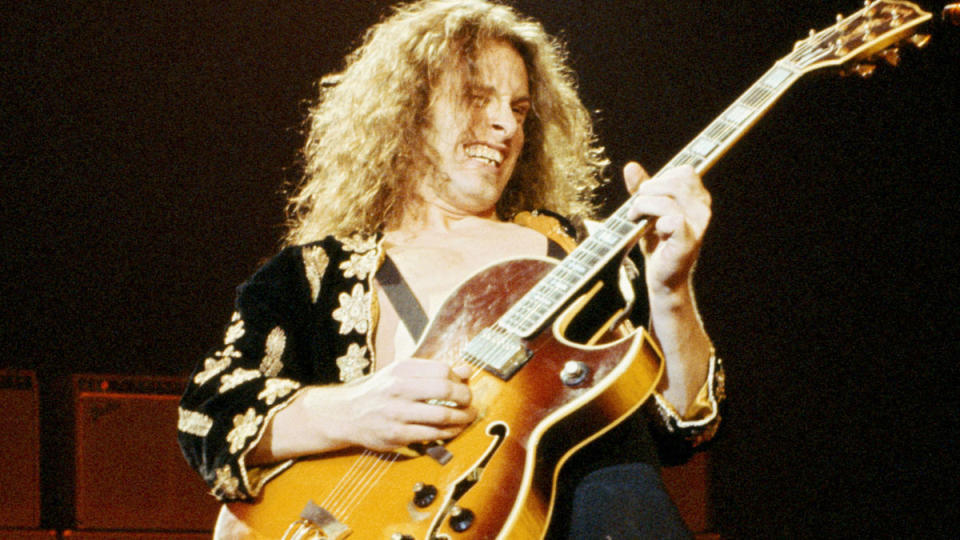

Nugent was forced to eventually move on to other Gibsons. “I went out and got another Byrdland, thank God, from Joe Massimino from Massimino Music – a sunburst, a beautiful guitar,” he says.

As Nugent’s solo career evolved, the sunburst “replacement” Byrdland played a prominent role at concerts and appeared on the cover of Nugent’s self-titled 1975 debut solo album. By 1979, Nugent owned more than 20 Byrdlands. “Quite honestly, I have used any number of my Byrdlands on various recordings and gigs over many years.”

The Byrd lands at the Hard Rock

In the mid-eighties, it became en vogue for rock stars to give their guitars to the Hard Rock Café (a practice that continues to this day). Eddie Van Halen famously gave one of his red-and-white striped Kramers to the Hard Rock in 1985. Nugent was no different; on April 8, 1986, he gave his original Byrdland to the Hard Rock at a ceremony in New York City.

“Only because I am a very strong individual am I able to even discuss this very painful, royal clusterfuck! Being the ultimate dumbass, having no clue of the potential value of a Ted Nugent original Byrdland, and since she would never make music with me again, I foolishly donated her to the Hard Rock.

“Somebody, please shoot me! We did try to get her back over the years, but to no avail. Thank God I can improvise, adapt and overcome tragedies, because that asinine decision could really haunt me if I were to let it.”

(“I find it hard to believe he would get rid of that,” McCarty adds...)

Life at the Hard Rock

After Nugent parted with the guitar, the first detailed, professional photographs of Nugent’s original Byrdland were taken. In the late ’80s, photographer John Peden shot the Byrdland for Guitar World’s monthly Collector’s Choice centerfold poster. Similarly, the Hard Rock had the instrument professionally photographed, presumably for archival purposes.

Like several other prized instruments owned by the Hard Rock, the newly acquired Nugent Byrdland seemed to have gone into hibernation in the HRC archives for more than a decade, waiting for a new home. In November 2003, the Hard Rock Café opened a location in Detroit.

On the face of the building entrance hung a 36-foot-tall replica of Nugent’s famous blonde Byrdland. The three-story neon guitar provided a guide path for what lay inside; Nugent’s original Byrdland was proudly displayed in his hometown. The venue drew lines of patrons and fans for weeks.

Given its history, and despite Erlewine’s impeccable surgical efforts, the guitar shows many scars. Noticeable cracks are evident in the seams of the spruce top. Stress fractures and pick scratches mar the face of the guitar. There is a terrible crack running through the blonde spruce on the left side of the old axe.

Modern-day relic enthusiasts would marvel at the aging: metal parts show signs of corrosion and the tailpiece is rusted. The words “volume” and “tone” are barely legible on the knobs. Present is a standard Nugent modification – an old Gretsch strap button used as the toggle switch cap.

We do have Nugent’s Byrdland. It’s a very cool piece in the Hard Rock’s collection. The guitar is not currently on display; it is being safely held in the Hard Rock’s secure storage facility

Unfortunately, after 15 years of operation, the Hard Rock Café in Detroit closed its doors as its building lease ended in 2019. The Nugent Byrdland once again disappeared into the Hard Rock vaults.

The Hard Rock’s Giovanni Taliaferro – VP of Memorabilia and Design – picks up the story: “We do have Nugent’s Byrdland,” he says. “It’s a very cool piece in the Hard Rock’s collection. The guitar is not currently on display; it is being safely held in the Hard Rock’s secure storage facility.

“The Hard Rock does have future plans to display the guitar; It would be part of a very cool project, but unfortunately, I am not able to share any other details at this time. We are hoping to have the guitar featured in a new construction, potentially shooting for 2025.”

The Byrd flies on

On the vintage market, the going rate of a mid-1960s Byrdland is well over $8,000; Taking into account the prices fetched from other famous guitarists selling off their main instruments, one has to wonder what amount the original Nugent Byrdland could command at auction.

Nugent has become as synonymous with the Gibson Byrdland as Hendrix is with the Stratocaster or Jimmy Page is with the Les Paul. His use of a hollowbody jazz archtop in a high-energy hard rock framework was truly ground-breaking.

“It’s all about tone, after all, right?” Nugent says. “That porous, breathing, living spruce has a voice all its own, especially in my hands through the never-ending experimental amplifiers I feed them through. I am miraculously blessed to increase my passion for guitar music every day, and the patterns, licks, grooves, bastardized chord structures, sounds and feedback turn me on more today than ever. Say Hallelujah!

“My guitar theme lines and licks erupt with a life of their own every time I plug in, so the song development process is as out-of-body organic as anything in life… The Byrdland’s hollowbody spruce feedback threshold forces my hands to work in a certain way to milk a delivery of percussiveness, blaring, sustain, staccato and feedback that is indescribably inspiring.”