Tarek El Moussa Was Once Arrested for Attempted Murder After Gang Fight: 'I Would've Been Killed' (Exclusive)

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

'It's part of my story,' the HGTV star tells PEOPLE while sharing in exclusive excerpt from his forthcoming book 'Flip Your Life'

Heidi Gutman-Guillaume; Tarek El moussa/instagram

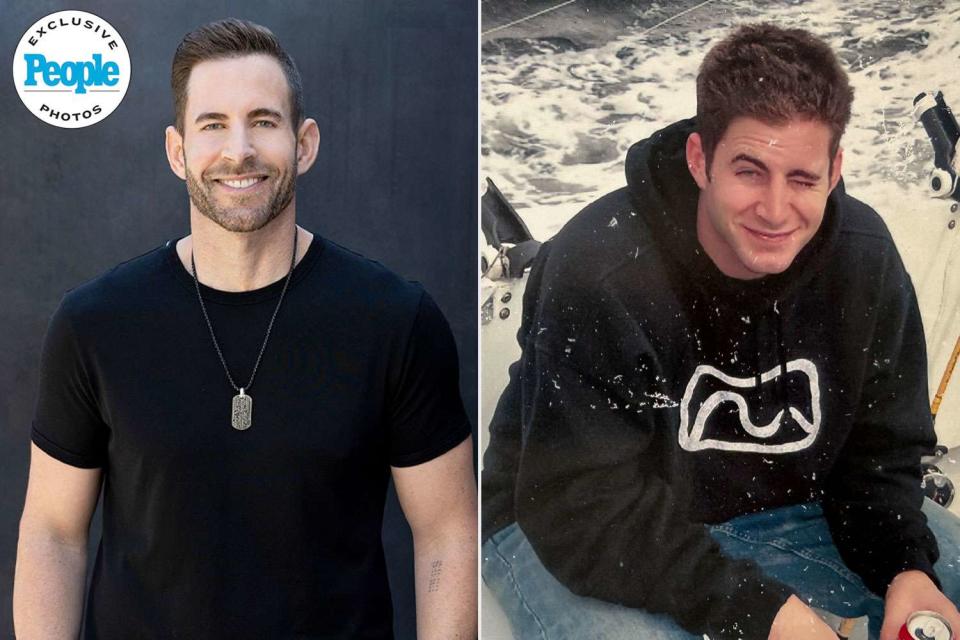

Tarek El Moussa tells shocking tales from his troubled youth in his new book, Flip Your Life: How to Find Opportunity in Distress—in Real Estate, Business, and Life (out Feb. 6) — and PEOPLE has an exclusive first look.

The HGTV star, 42, has been open with fans about some of the darker periods of his life: overcoming addiction, beating cancer and navigating a very public divorce from his Flip or Flop co-star Christina Hall, to name a few.

But in his new book, he opens up about growing up in a rough neighborhood and shares stories that will surprise even longtime fans — the most brutal of which can be found in the exclusive excerpt below.

As a teen, the Flipping El Moussas host writes, he was involved in a gang fight that got him arrested and charged with attempted murder, and spent a short time in a juvenile detention center.

"It's part of my story," he tells PEOPLE of his decision to include the harrowing details in his book, which is part self-help guide, part memoir. "We're all a product of our environment, and I grew up in that environment. In order to thrive in that environment, you have to do certain things."

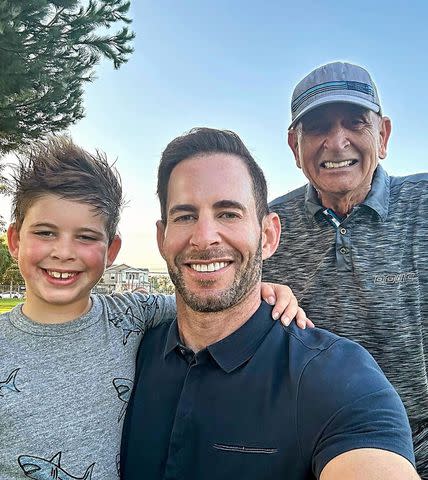

Tarek El moussa/instagram

El Moussa says there were many more fights for him like the one he includes in the book. "That one had the most extreme consequences for me, but that was not the most extreme," he recalls. "I've been in shootings, I've been in knife fights, I've been hit in the face with a bat. You name it, I've had it."

More than 20 years later, he says, he was lucky to get away from that environment, but it shaped the adult he's become.

"That's why I shared what I shared. [To show] you can literally be a gang banger right now, robbing people, and you can flip your life. Anybody can change. They just have to want to."

Looking back on the day of his arrest, he says, "I'll never forget. I was terrified when I was there, because the charges I had were really bad charges, and I didn't know if I was going to be there for days or years."

That fight was a turning point for him. "I still got in a little bit of trouble here and there," he says, "but it was a big enough incident where it made me really, really think about things."

--

Both of my parents were fully aware of the dangerous alternatives out there. The neighborhood where we lived was not so much white collar or blue collar as “no collar.” True, the little pocket where we lived had some up-and-comers; it was where I got my first glimpse of some of the finer things in life. But it was the least rough neighborhood in a very rough area. Parts of Lakewood and Buena Park were heavily influenced by gangs. If nothing else, I was determined to conform to the gangs’ sense of style. In junior high, I started waxing my hair and sleeping with a panty- hose cap on. I wanted to make sure my hair would be slicked back enough for school the next day. In the morning, I wouldn’t come out of the bath- room until every hair was in place and my pants had just the right degree of “sag.” Since Angelique and I shared a bathroom, this routine drove her crazy. And I lost count of how many pairs of my mom’s pantyhose I cut up (but I’m sure she remembers!).

But of course, the neighborhood gangs stood for something much more serious than a dress code. By the time I started junior high school, I was looking over my shoulder a lot. One after another, guys I knew from school got drawn into the gangs, and I saw the awful consequences when that happened. I made a conscious decision to point my life in a different direction. But first I had to survive.

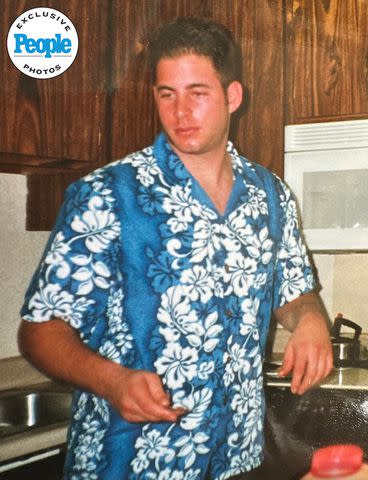

Courtesy Dominique El Moussa-Arnould

At the end of my sophomore year, my parents’ worst fears were realized. I was barely making Cs in school, and I had a terrible attitude. My girlfriend was a senior, and I had promised to be there on the night she graduated. That same day, however, a guy I knew learned that his girl- friend had started dating someone else. I can’t remember all the details of this Romeo-and-Juliet story, but the guy was heartbroken and furious. Word got out, and soon both sides—my friend’s, and the rival boyfriend’s—decided that scores must be settled, immediately. Later that afternoon, about fifteen of us went to a local park, ready to fight the rival boyfriend and his friends with our fists...or so I assumed.

Minutes after we got there, it was obvious that our opponents had other plans. Two SUVs rolled up and unloaded a bunch of guys whose hands were taped up, for protection. They had baseball bats and crowbars. “Okay,” I told myself; “we outnumber them—we have more bodies, but they have weapons.” The two sides squared off in the middle of the park. A few words were exchanged, then mayhem erupted. Fists flew, and so did the baseball bats. During the free-for-all, an older guy—maybe nineteen or twenty—stepped toward me and swung his bat. I tried to jump out of the way, but the bat connected, hard—hard enough to break my ribs. As a reaction, I dropped my arm and knocked the bat out of his hands. I grabbed the bat and hit him in the head. He dropped to the pavement and went unconscious.

When I looked up, the park was a mess, all I could hear were police sirens in the distance, and all of my friends had left. There were bodies everywhere. But then, across the park, I saw that a “second wave” was gathering. And these weren’t teenage boys; these were the older brothers of the guys we had just fought with. Some were obviously in their thirties. And they were running at me with crowbars. I was seventeen, and in that moment, I was all alone. That’s when the police pulled up and saved my life.

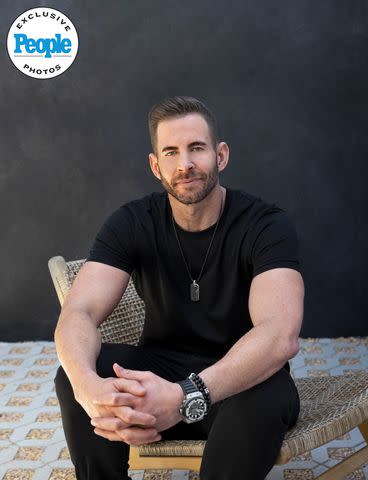

Heidi Gutman-Guillaume

I can’t say for sure what happened next, but I must have blacked out. When I came to, I was sitting in the back of a police car, in handcuffs, charged with assault and battery, aggravated assault, attempted murder, and assault with a deadly weapon. Today I’m convinced that the police arrived at exactly the right moment. If I hadn’t been arrested, I would have been killed.

I spent that night—the night I was supposed to be honoring my girlfriend by watching her graduate—in juvenile detention in the city of Orange. As the cell door clanged shut, I was terrified. The charges against me were very serious, and I didn’t know if I was going to be there for a day, a week, or years. The cots were bare metal, and I had no idea that the bedsheets were stored inside the pillowcase, so I shivered all night, from fear and cold. Since they wouldn’t let us have toothbrushes, I had to brush my teeth with a sponge.

On the second night, I got a cellmate. With his bald head, his wrinkled neck, and tattoos all over his body, he looked like he was forty—a whole lot older than people you’d expect to see in “juvie.” He was a scary-looking dude, and he had obviously been there before. When he saw me lie down on my metal cot, he told me to look in my pillowcase for my sheets. Meanwhile, my parents, who were frantic, had reached out to an attorney and were working to get me out. After some investigation, the prosecutors figured out that I had used the other guy’s bat in self-defense, during mutual combat. It helped that I had a clean record. They dropped the charges and sent me home, but I was on house arrest for about a week. I was still in pain, and it took a few weeks for my ribs to heal, but I knew I was lucky to be alive.

Shortly after this episode, a psychiatrist put me on a medicine called Dexedrine, a powerful drug that reduces impulsivity. This was the first time I’d been medicated for my ADHD, and the change I experienced was incredible. It was as if everything suddenly slowed down. I was able—finally—to focus in school. By the time I graduated, my GPA had climbed from a C average to a 3.8, almost straight As. But there were other consequences that were not so great. The doctors made me “normal” for a while, and I learned that “normal” makes good grades—but I knew something was off, and I hated it. In fact, I’m sure those early doses were fifty times stronger than the one I take today. Overnight, I went from wild-eyed, hyperactive Tarek to a guy who just sat there, stoned off his ass, saying nothing and feeling frozen. The point is that it took a while to get the dosage right, and the medication hasn’t “cured” my ADHD, by any means, but I’m deeply grateful for it.

Meanwhile, I promised myself I would never end up in that kind of situation ever again. On the one hand, I’ve never in my life gone looking for a fight. Even in my stupid teenage years, I only fought to protect someone else. On the other hand, this whole juvie experience scared the hell out of me. Walking across the park that day, I had come face to face with the very worst embodiment of a “crew,” and they had come very close to killing me. I saw that I would have to redirect my instinct to fight. I needed to throw myself into fights that really mattered, ones that wouldn’t get me killed.

Excerpted from Flip Your Life: How to Find Opportunity in Distress—in Real Estate, Business, and Life by Tarek El Moussa. Copyright © 2024. Available from Hachette Go, an imprint ofHachette Book Group, Inc.

For more People news, make sure to sign up for our newsletter!

Read the original article on People.