A Sweet Surface Hid a Troubled Soul in the Late Karen Carpenter, Who Would Have Been 70 Today

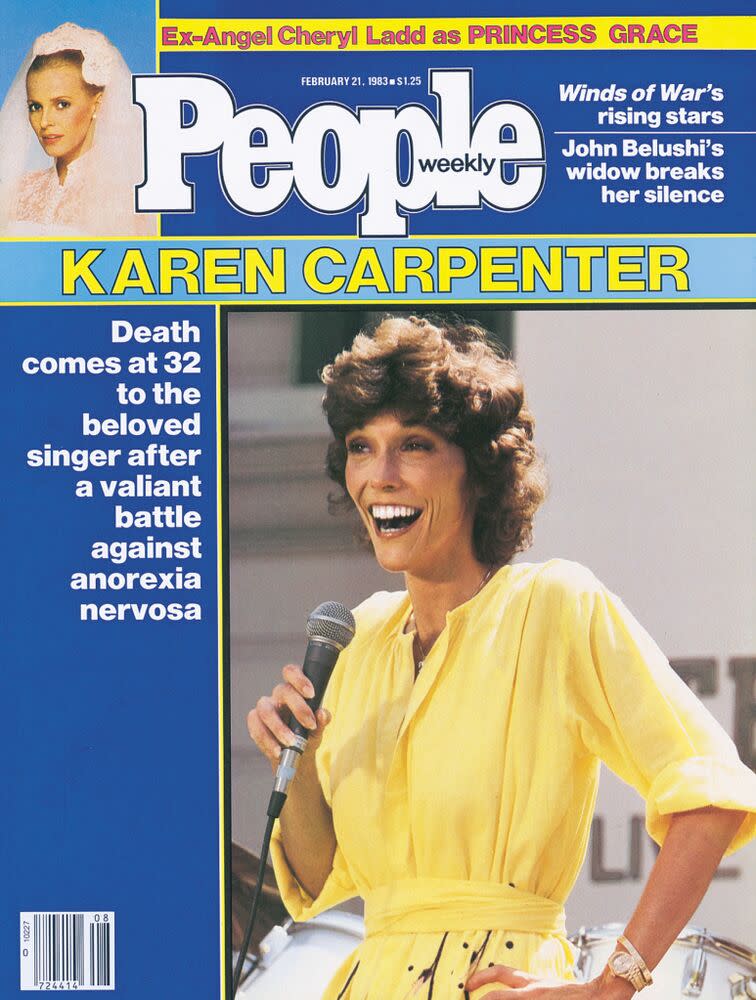

On Feb. 4, 1983, singer Karen Carpenter fell victim to heart failure brought on by the chemical emetine after an eight-year battle with anorexia nervosa. Today, March 2, 2020, she would have been 70 years old. We pay tribute by running our cover story from the Feb. 21, 1983 issue of PEOPLE below.

Iced tea was the hardest drink she consumed, and the only needles she used were for needlepoint. Her weirdest stash was a collection of Mickey Mouse memorabilia. The flagrant comet tail of self-indulgence so familiar in plummeting stars like Elvis Presley and John Belushi did not mark Karen Carpenter’s life—or her death of heart failure on Feb. 4 at the age of 32. Yet for all the soothing middle-of-the-road appeal she and her composer-arranger brother, Richard, 37, brought to 41 Carpenters records—which have sold 80 million copies and won three Grammy Awards—she had led a long, lonely struggle against another form of self-destruction, anorexia nervosa.

She collapsed at about 9 a.m. in the wardrobe closet of the room her parents have always kept for her at the family home in suburban Downey, Calif., about 30 minutes from Los Angeles. Downey firemen entered the closet to find Karen slumped nude on the floor, her nightgown draping her body. She had apparently just begun to dress for the day. At the request of the rescue workers, Karen’s grief-stricken mother, Agnes, was escorted from the room by husband Harold.

The rescuers at first detected a faint pulse in Karen’s neck that made them think, says paramedic Bob Gillis, that “she had a good chance to survive.” But then she went into cardiac arrest. Racing over from his house a few minutes away, Richard Carpenter arrived just before the paramedics carried his sister out to the ambulance. Despite continuous efforts to resuscitate her, Karen was pronounced dead at Downey Community Hospital at 9:51 a.m.

A wave of grief spread among those who had known her. “She was a magical person with a magical voice,” says Burt Bacharach, who in 1963 had written the song which became the Carpenters’ first hit, Close to You. Adds Paul Williams, author of their second gold smash, We’ve Only Just Begun: “Karen and Richard’s music brought the American family together during a period when there was very little else it could share.” Williams’ apparent reference to the turbulent Vietnam and Watergate eras was apt. The Carpenters were at their zenith in 1973, when then President Richard Nixon introduced the duo to a glittering White House audience as “young America at its very best.”

In the aftershock, friends wondered if Karen had tried too hard to live up to that description, had perhaps died trying. Hers was the “good girl’s” disease—a compulsive urge to control weight, primarily among female hyper-achievers, that leads to such extremes as self-induced vomiting and taking huge doses of laxatives. An autopsy revealed no immediate explanation for her heart failure. But after a long bout with anorexia, says Dr. Joel Yager of UCLA’s Eating Disorders Clinic, “the most common cause of death is low serum potassium, which can cause an irregularity in the heartbeat.” Karen had spent almost all of 1982 in New York undergoing treatment, and had lifted her weight from a gaunt 85 to 108 pounds—very near normal for her frame and height, 5’4″. But, as anorexia expert Dr. Raymond Vath of Seattle points out, doctors learned only two months ago that the greatest strain is put on an anorectic’s heart when lost weight is regained.

Paul Bloch, the Carpenter family’s PR man, downplays the anorexia connection. “Karen was a vibrant and energetic person,” he insists. Concurs Gil Friesen, president of A&M Records, the Carpenters’ label, “Karen was the girl next door, always up even when she was down.” Typical signs of anorectics, says Dr. Yager. “It’s common for them to be sweet,” he says. “Many keep their emotions inside. They take care of other people, but they don’t take care of themselves.” Karen’s condition was alarmingly obvious. A co-worker who had seen her early last year said she resembled “a living skull.” Added another, “She appeared to be a tormented and unhappy woman.”

Indeed, as far back as 1971, when the Carpenters were soaring on their early hits, Karen was “psychotic about her weight,” an acquaintance recalls. “She had a classic pear-shaped figure—she was chubby, and she was very self-conscious about it.” Tom Burris, the real estate developer whom Karen married in 1980 and from whom she was separated last year, says she was suffering from anorexia “for about nine years.” The term, though, was not widely known in 1975, when Karen slipped frighteningly from her performing weight of 110 to a shadowy 90 pounds. It took two months of bed rest at home to recuperate from physical and nervous exhaustion brought on by some 250 days a year of arduous touring. “It was sickening,” she told PEOPLE after getting back on her feet the next year. “Suddenly it wasn’t fun anymore.”

Though much had changed in her life by 1981, Karen was still taking a vengeful attitude toward her weight. Distraught, she reached out to Pat Boone’s daughter, Cherry Boone O’Neill, who was finishing a book about her own anorexia, Starving for Attention. They spoke once in person, then three times on the telephone.

“She didn’t sound panicked, but she felt that she really needed some help,” recalls Cherry, now 28. “Karen was having particular problems with laxatives. She could not believe she could ever get to a point where she was not dependent on them.” O’Neill, who herself had often taken laxatives by the box to “drop 10 or 15 pounds overnight,” urged her friend to “get away from the pressures of L.A. and show business and concentrate on her own life and survival.” She told Cherry: “I’m going to do it. I’ll get well—it’s just so damn hard.”

Like Cherry, Karen was raised in an unusually close-knit family. The children of a printer and a homemaker, Karen and Richard moved with their parents from New Haven, Conn, to Downey in 1963. “Karen grew up in a very tight, parentally dominated world,” says a longtime friend. “Her parents are very nice people, but they controlled her early life and continued to try and do so over the years.” One incident from early in Karen and Richard’s career may be typical. Agnes Carpenter called her offspring at their Cincinnati motel to scold them for not having signed autographs backstage following a show in Hershey, Pa. after a fan wrote to complain. Dutifully, the youngsters called the fan and apologized.

Anorectics, notes Cherry, are usually the children of authoritative parents. “Such a person,” she says, “does not rebel.”

Richard was the first to take up music, inspired by his “Three B’s—the Beatles, Beach Boys and Burt Bacharach.” A sports fan, Karen was handed a glockenspiel in the high school marching band and figured it out. Wielding chopsticks on bar stools, she eventually taught herself percussion well enough to tap along with Dave Brubeck’s rhythmically challenging album, Time Further Out. The duo won a Hollywood Bowl Battle of the Bands, and after three years of scrounging for work were signed by A&M co-founder Herb Alpert.

“It was interesting the way they made records,” a close colleague observes. “Richard laid out all the basic tracks, and then Karen would come in and sing. He was a tyrant in the studio. She would spend a lot of time on her vocals, and was always hard on herself.” An ex-employee of A&M agrees: “It always seemed as if she were under Richard’s thumb.”

Barry Manilow observes that Karen clearly “adored” Richard. “She couldn’t speak highly enough of him. To her, he was a genius.” Yet it was clearly Karen’s voice that made the Carpenters click. “I’m sure she felt she had to measure up, that the whole act kind of hinged on her,” Cherry O’Neill says. “That’s an awful lot of pressure for one individual.”

Karen’s apparent solution, suggests Cherry, was classic: “When you start denying yourself food, and begin feeling you have control over a life that has been pretty much controlled for you, it’s exhilarating. The anorectic feels that while she may not be able to control anything else, she will, by God, control every morsel that goes in her mouth.”

Karen’s anorectic episodes in the ’70s seem to have waxed and waned, and in 1976, after her two-month recuperation at home, she made a stab at independence from her parents by moving into her own large apartment in a Century City condo. In 1980 her mother urged Karen to attend a dinner at the chic Ma Maison restaurant that Karen wanted to skip, and there she met Tom Burris, a 39-year-old divorcé with an 18-year-old son. Two months later they were engaged.

Although Burris insists “We always got along, always cared about each other,” they soon grew apart. “Karen was dealing with her anorexia and her career, I was dealing with my real estate problems,” he explains. “I feel totally guilty, like I’d like to reverse everything. I tried to work with her. I got her in touch with a doctor, but she wouldn’t admit she had an eating problem. We both tried, but we just couldn’t work it out.”

Later Karen reached out to the physician who treated Cherry O’Neill, Dr. Vath of Seattle. “She wanted a quick fix,” he recalls. “She told me she had all these contracts and just had to get well. But I said, ‘No, Karen, we don’t know how to treat this rapidly. It would take a minimum of a year, probably three, to get you well.’ ” Finally she agreed to a course of treatment in a New York hospital, where she took two-hour treatments every day for nearly a year. But even there, as Dionne Warwick discovered, Karen’s weight rose faster than her spirits. “She had gone through a lot of depression and sadness,” said Warwick. “When a marriage breaks up, it’s a devastating thing.”

Last December Karen returned to L.A. O’Neill was concerned: “Putting yourself in the same environment where the problems first developed without totally recovering can cause setbacks.” But by most accounts Karen was suffused with new energy. She was planning to record an album this spring. “Karen was getting along great,” insists her longtime hairdresser, Arthur Johns, who gave her a perm before New Year’s and says she intended to come back to have her hair streaked bronze. “She had started writing songs for the first time. She wasn’t the type of person to mop the floor with her tears.” Clearly, Karen Carpenter intended to conquer despair. “I have,” she told Warwick just two weeks before her death, “a lot of living left to do.”

— Eric Levin; Suzanne Adelson; Gail Buchalter; Joseph Pilcher