The Supreme Court Just Went Medieval on Executions and the Eighth Amendment

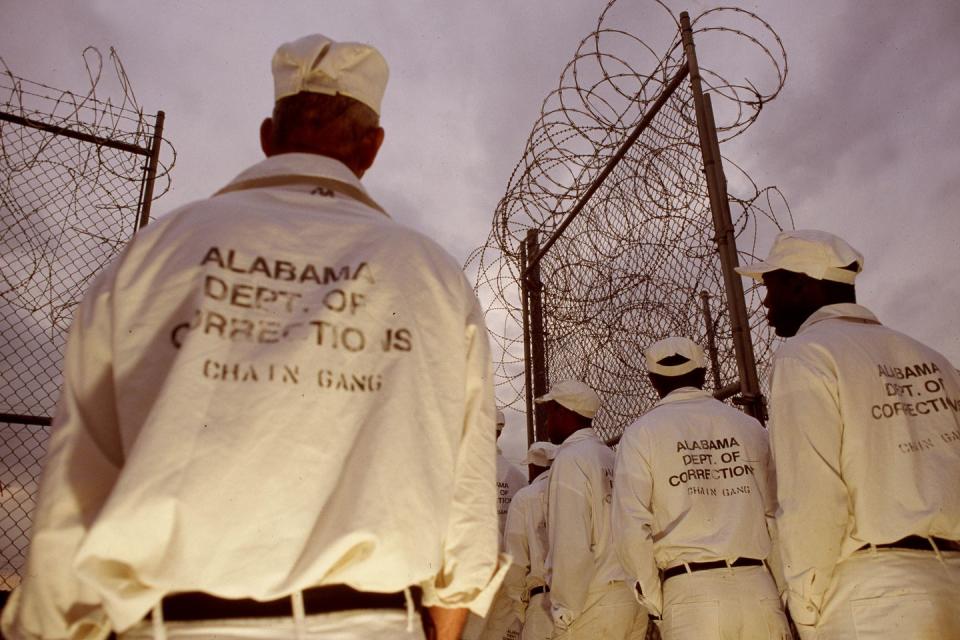

In 1995, Larry Hope was stacking his time at the Limestone Prison in Alabama. Larry Hope was a difficult inmate and Limestone had a rather unique solution to the problem of difficult inmates. They were chained to a hitching post in the prison yard for as long as the authorities saw fit to leave them there. Larry Hope was difficult enough that he was chained up there twice. Legal papers later entered on his behalf told his story.

On May 11, 1995, while Hope was working in a chain gang near an interstate highway, he got into an argument with another inmate. Both men were taken back to the Limestone prison and handcuffed to a hitching post. Hope was released two hours later, after the guard captain determined that the altercation had been caused by the other inmate. During his two hours on the post, Hope was offered drinking water and a bathroom break every 15 minutes, and his responses to these offers were recorded on an activity log. Because he was only slightly taller than the hitching post, his arms were above shoulder height and grew tired from being handcuffed so high. Whenever he tried moving his arms to improve his circulation, the handcuffs cut into his wrists, causing pain and discomfort.

The second time was worse.

On June 7, 1995, Hope was punished more severely. He took a nap during the morning bus ride to the chaingang's worksite, and when it arrived he was less than prompt in responding to an order to get off the bus. An exchange of vulgar remarks led to a wrestling match with a guard. Four other guards intervened, subdued Hope, handcuffed him, placed him in leg irons and transported him back to the prison where he was put on the hitching post. The guards made him take off his shirt, and he remained shirtless all day while the sun burned his skin. He remained attached to the post for approximately seven hours. During this 7hour period, he was given water only once or twice and was given no bathroom breaks. At one point, a guard taunted Hope about his thirst. According to Hope's affidavit: "[The guard] first gave water to some dogs, then brought the water cooler closer to me, removed its lid, and kicked the cooler over, spilling the water onto the ground."

Larry Hope sued and his case made it all the way up to the Supreme Court where, in 2002, by a 6-3 majority, Larry Hope won and the hitching post was outlawed. Writing for the majority in Hope v. Pelzer, Justice John Paul Stevens said:

As the facts are alleged by Hope, the Eighth Amendment violation is obvious. Any safety concerns had long since abated by the time petitioner was handcuffed to the hitching post because Hope had already been subdued, handcuffed, placed in leg irons, and transported back to the prison. He was separated from his work squad and not given the opportunity to return to work. Despite the clear lack of an emergency situation, the respondents knowingly subjected him to a substantial risk of physical harm, to unnecessary pain caused by the handcuffs and the restricted position of confinement for a 7-hour period, to unnecessary exposure to the heat of the sun, to prolonged thirst and taunting, and to a deprivation of bathroom breaks that created a risk of particular discomfort and humiliation. The use of the hitching post under these circumstances violated the "basic concept underlying the Eighth Amendment[, which] is nothing less than the dignity of man." Trop v. Dulles,356 U. S. 86, 100 (1958). This punitive treatment amounts to gratuitous infliction of "wanton and unnecessary" pain that our precedent clearly prohibits.

The obvious cruelty inherent in this practice should have provided respondents with some notice that their alleged conduct violated Hope's constitutional protection against cruel and unusual punishment. Hope was treated in a way antithetical to human dignity-he was hitched to a post for an extended period of time in a position that was painful, and under circumstances that were both degrading and dangerous. This wanton treatment was not done of necessity, but as punishment for prior conduct.

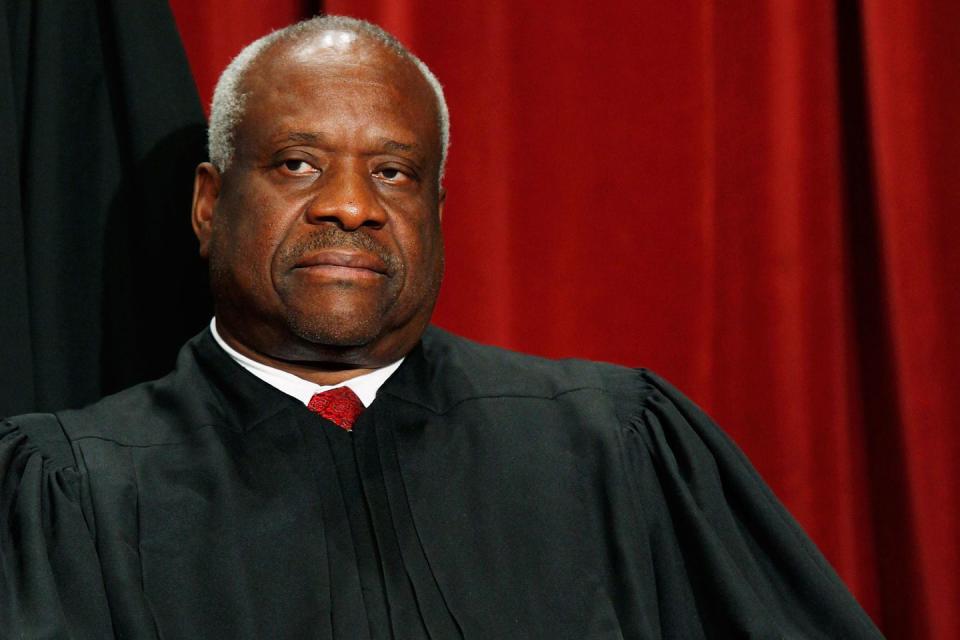

What was significant about the decision, besides its strong reinforcement of Eighth Amendment freedoms, was a remarkable dissent by Justice Clarence Thomas, who saw nothing at all wrong with chaining Larry Hope to a pole in the hot Alabama sun for seven hours. Thomas's dissent drew extensively on the doctrine of qualified immunity granted to officials like prison guards by virtue of their work, and on his understanding that the named defendants did not themselves fasten Hope to the hitching post. But Thomas also made it clear that he considered fastening Hope to the hitching post was merely business as usual in a prison.

If, for instance, attaching petitioner to a restraining bar amounted to the "gratuitous infliction of 'wanton and unnecessary' pain," ante, it is curious that petitioner, while handcuffed to the bar on May 11, chose to decline most of the bathroom breaks offered to him. Respondents also affixed petitioner to the restraining bar for a legitimate penological purpose: encouraging his compliance with prison rules while out on work duty.

At which point, the nit-picking began in earnest.

In Gates, the Court of Appeals listed "handcuffing inmates to [a] fence and to cells for long periods of time" as one of many unacceptable forms of "physical brutality and abuse" present at a Mississippi prison. Id., at 1306. Others included administering milk of magnesia as a form of punishment, depriving inmates of mattresses, hygienic materials, and adequate food, and shooting at and around inmates to keep them standing or moving. See ibid. The Court of Appeals had "no difficulty in reaching the conclusion that these forms of corporal punishment run afoul of the Eighth Amendment."...

For example, in referring to the fact that prisoners were handcuffed to a fence and cells "for long periods of time," the Court of Appeals did not indicate whether it considered a "long period of time" to be 1 hour, 5 hours, or 25 hours. The Court of Appeals also provided no explanation of the circumstances surrounding these incidents. The opinion does not indicate whether the handcuffed prisoners were given water and suitable restroom breaks or whether they were handcuffed in a bid to induce them to comply with prison rules.

In other words, Mr. Justice Thomas decided that there were circumstances in which it was constitutional to fasten a guy to a pole for seven hours without allowing him a drink of water, which led a lot of people to believe at the time that Mr. Justice Thomas-and the late Justice Antonin Scalia, who joined him in dissent-had missed his proper time as a judge by about three centuries. Nevertheless, there was some comfort in the fact that the Court had resoundingly rejected medievalism as a proper penal philosophy. Not any more.

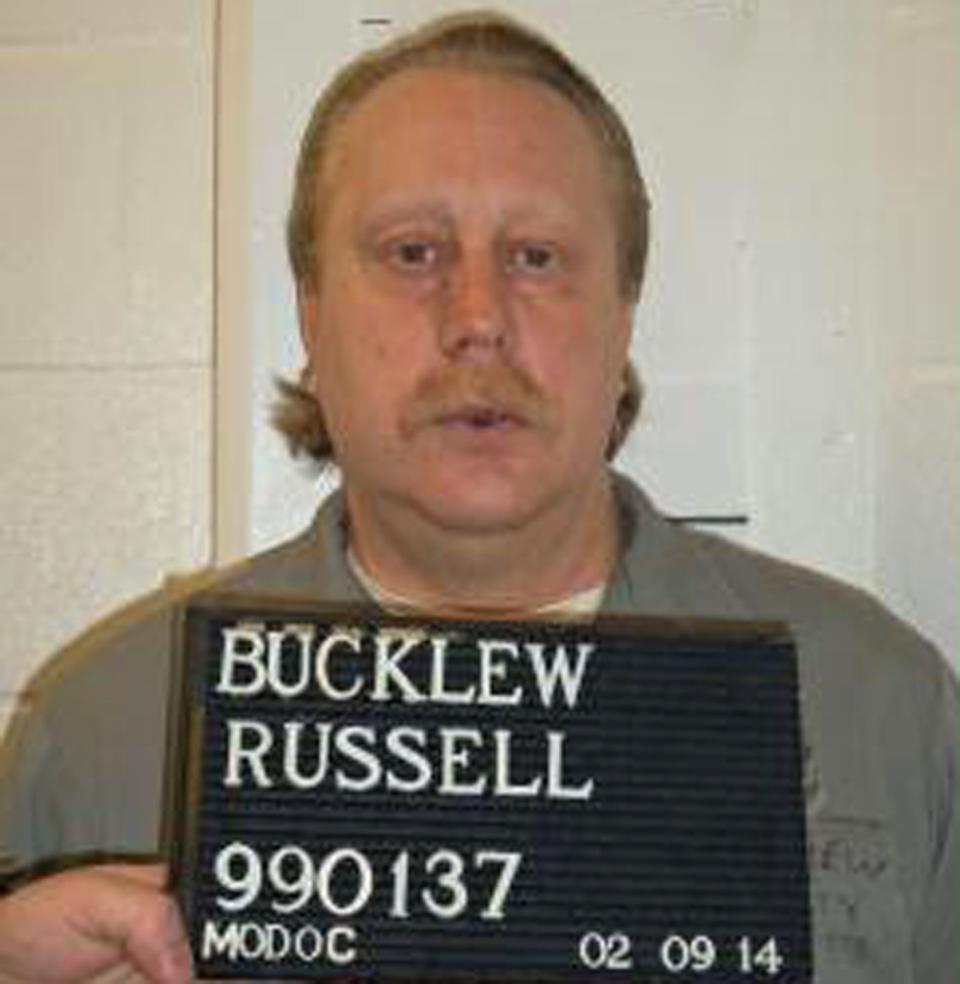

On Monday, in the case of Bucklew v. Precythe, the brand-new, shiny conservative majority decided by 5-4 that, for all practical purposes, Justice Thomas had been right all along. The case involved a death-row inmate in Missouri named Russell Bucklew, who is scheduled to die by lethal injection for a murder-rape-and-assault spree in 1996. Bucklew has a condition by which vascular tumors grow in his head, neck, and throat. Bucklew and his lawyers argued that this condition would cause Bucklew to choke to death on his own blood if he were to be executed by injection in the conventional manner. They suggested killing him by nitrogen gas instead.

The Court rejected that alternative in its majority opinion, which was authored by Justice Neil Gorsuch, who went sailing past even Thomas's arguments in Hope right back to the days of the rack and thumbscrews. In the Supreme Court especially, nobody expects the Spanish Inquisition. Gorsuch wrote:

The Constitution allows capital punishment. In fact, death was “the standard penalty for all serious crimes” at the time of the founding. Nor did the later addition of the Eighth Amendment outlaw the practice. On the contrary-the Fifth Amendment, added to the Constitution at the same time as the Eighth, expressly contemplates that a defendant may be tried for a “capital” crime and “deprived of life” as a penalty, so long as proper procedures are followed.

While the Eighth Amendment doesn’t forbid capital punishment, it does speak to how States may carry out that punishment, prohibiting methods that are “cruel and unusual.” What does this term mean? At the time of the framing, English law still formally tolerated certain punishments even though they had largely fallen into disuse-punishments in which “terror, pain, or disgrace [were] superadded” to the penalty of death. 4 W. Blackstone, Commentaries on the Laws of England 370 (1769). These included such “[d]isgusting” practices as dragging the prisoner to the place of execution, disemboweling, quarter- ing, public dissection, and burning alive, all of which Blackstone observed “savor[ed] of torture or cruelty.”...

What does all this tell us about how the Eighth Amendment applies to methods of execution? For one thing, it tells us that the Eighth Amendment does not guarantee a prisoner a painless death-something that, of course, isn’t guaranteed to many people, including most victims of capital crimes...Instead, what unites the punishments the Eighth Amendment was understood to forbid, and distinguishes them from those it was understood to allow, is that the former were long disused (unusual) forms of punishment that intensified the sentence of death with a (cruel) “‘superadd[ition]’” of “‘terror, pain, or disgrace.'"

This is originalism turned barbarism. If a method of execution was considered cruel and unusual at the time the Constitution was written, that is the only kind of method that should be declared cruel and unusual in 2019. And that it comes from Gorsuch should be no surprise to anyone.

Return with us now to those thrilling days of yesteryear-2017, to be exact, and to a man named Alphonse Maddin. Maddin was a truck driver in the employ of TransAm trucking. His truck broke down on a road in Illinois on a night on which the temperature dropped to 14-below. Maddin called the company and they told him to stay with his rig and inside his unheated cab. Three hours later, on the verge of hypothermia, Maddin drove away in search of a warm place to wait. The company fired him. Maddin took the company to court and won. The lone dissenter on the Tenth Circuit was Justice Neil Gorsuch, who explained that, while he was generally opposed to freezing to death, the company was within its right to fire him.

The Department of Labor says that TransAm violated federal law, in particular 49 U.S.C. § 31105(a)(1)(B). But that statute only forbids employers from firing employees who “refuse[] to operate a vehicle” out of safety concerns. And, of course, nothing like that happened here. The trucker in this case wasn’t fired for refusing to operate his vehicle. Indeed, his employer gave him the very option the statute says it must: once he voiced safety concerns, TransAm expressly - and by everyone’s admission - permitted him to sit and remain where he was and wait for help.

When Gorsuch faced the Senate Judiciary Committee, then-Senator Al Franken confronted Gorsuch with this case, he explained his decision in as bloodless a way as humanly possible.

“I said it was an unkind decision, I said it might have been a wrong decision, a bad decision, but my job isn’t to write the law, senator, it’s to apply the law. If Congress passes a law saying the trucker in those circumstances gets to choose how to operate his vehicle, I’ll be the first in line to enforce it. “

This sent Franken into a memorable soliloquy.

“He gets fired, and rest of the judges all go, ‘That’s ridiculous, you can’t fire a guy for doing that,'...Everyone here would have done exactly what he did – and I think that’s an easy answer. It is absurd to say this company is in its rights to fire him. … I had a career in identifying absurdity. And I know it when I see it. And it makes me question your judgment.”

But watching Gorsuch smoothly and (yes) coldly relate the basis for this decision is something that stayed with me. There wasn't an ounce of humanity in what he said. He knew his nomination was in the bag, and he knew that everyone in the Senate knew as well.

What did he care about the fact that Alphonse Maddin's choices on that cold night were either to freeze to death, or to drive a dangerously unstable truck? Neil Gorsuch never was going to know anybody facing a decision like that. What does Neil Gorsuch care if Russell Bucklew is essentially tortured to death? He will never know anybody in that situation, either. And, down the bench, Clarence Thomas can take satisfaction in the fact that the law has moved far enough backwards that it's caught up with him and the Alabama hitching post.

Respond to this post on the Esquire Politics Facebook page here.

('You Might Also Like',)