Super Bowl 2020: What it's like to make a playoff-winning field goal

Morten Andersen was walking up and down the sidelines, focusing on his breathing, focusing on lowering his blood pressure. It was overtime in the 1999 season’s NFC championship, and Andersen’s Falcons were driving into Minnesota Vikings territory.

The kicker lived by mantras like “when the skillset matches the task, there’s no pressure,” but still — this was a monumental task: in moments, he would be called on to kick a field goal, on hostile ground, that would eliminate the Vikings and send the Falcons to their first Super Bowl.

Andersen looked down the sideline. About 20 of his teammates were kneeling, holding hands.

“Oh my gosh, what are they doing?” Andersen thought. “They don’t think we’re going to win.”

Andersen had prepared for moments like this for his entire career. “I knew we were going to win, I just didn’t tell anybody,” he would say, years later. “They weren’t in control. I was driving the car.”

We’re in the NFL’s crunch time, the moment where every misfire can end your season, where glory awaits the closer the clock ticks to 00:00. GOAT or goat, what’s it going to be?

Nowhere is this all-or-nothing dynamic more evident than the kicking game, when an entire team’s fortunes rest on the toes of the team’s smallest player. And nowhere is the tension around the kicking game higher than in the closing seconds of a playoff game, when a full year’s work comes down to whether a booted ball flies true or wavers.

Here’s a bit of trivia for your Super Bowl party: only four Super Bowls have effectively ended on a field goal attempt. Of those, three involved a kick from a tie to a win. The only all-or-nothing, victory-or-defeat kick in Super Bowl history remains Scott Norwood’s attempt to win for Buffalo in Super Bowl XXV … and you know how that turned out. (The winners: Baltimore’s Jim O’Brien in Super Bowl V, New England’s Adam Vinatieri in Super Bowls XXXVI and XXXVIII.)

This weekend’s Super Bowl features two teams separated by a mere point-and-a-half in pregame betting spreads, and that means there’s a decent chance the season could end up on the toe of a kicker. It’s a lonely situation, being out there on the field waiting for the snap, knowing the next four seconds will determine the arc of the rest of your life. What’s that like?

In the interest of keeping a positive mindset, we asked kickers who made three of the most significant field goals in postseason history what they went through in the seconds before their famous kicks … and for each one of them, it all started years before the big moment.

‘Adult Diaper City’

“The hardest thing about kicking is that it comes so infrequently,” said Rich Karlis, who kicked for the Denver Broncos in the 1980s. “You can’t get into a groove like a position player who’s in there for several plays. You have to concentrate your focus for that one swing. You never know when your number is going to be called, and it might define your career.”

“The more you bleed in peace, the less you bleed in war,” Andersen said, a variant of an old George Patton quote. Preparation, for Andersen, is the key for any field-goal kicker facing a high-pressure situation.

“The two things you can control are effort and attitude,” Andersen said. “Everything else is white noise. It doesn’t matter if you’re inside, outside, day, night, Green Bay, New Orleans.” He would spend practices simulating every single situation he could think of — he’d have the defense scream trash about his mother at him, he’d make it as difficult as possible for himself. He’d ask the long snapper to snap it high, he’d ask the holder to put the ball laces-in. Anything to increase the challenge while there was no pressure.

The reason why kicking a field goal in the playoffs seems so terrifying to those of us watching it from the stands is that we haven’t had decades of mental training for this moment. Imagining a random audience member vaulted onto the field to kick a crucial field goal, Andersen just laughs.

“They would [expletive] their pants, buddy! I got news for you, it would be Adult Diaper City.”

With enough training, though, even the most terrifying situations can come down to routine. “In games where you feel the ground shake a little bit, stomping and screaming becomes white noise,” said Karlis. “That’s the difference between guys who can make it in the regular season versus the postseason, guys who are really good in practice versus guys who get it done in games.”

By Andersen’s accounting, more than 600 guys tried to take his job. All failed. He’d kick into 8-foot-wide field goals — in from the usual 18 feet, six inches — and he’d use that skill to intimidate the hell out of anyone trying to kick him out of camp. Once you’ve booted a ball through an 8-foot gap, 18 feet looks as wide as the sky.

‘You can’t ice ice’

“If the offense got to the 50-yard line, that’s when I put my hard hat on, my helmet on,” Andersen said. “I was in the net for a couple warmup kicks. We were one first down away from field-goal range, so I was always situationally aware of where we were on the field.” He would pace, he would move around all over the sideline to keep warm.

“You shouldn’t ever be surprised on the sideline,” said Joe Nedney, who kicked for nine teams from the mid-1990s to the mid-2000s. “You should already be prepared any time the offense is getting close to your range.” Preparation, though, comes in many different forms.

“I mostly just tried to isolate myself,” Karlis said. “I would stay around the kicking net, and not engage in a whole lot of conversation. I wasn’t worried about field position, the conditions of the field, the weather. I would more or less try to distract myself with my process.”

Karlis focused on his swing, using repetition to block negative thoughts. “You really only need to concentrate really hard for about 1.3 seconds,” Karlis said. “But you’ve got to have a laser-beam focus at that point.”

Nedney took the opposite approach, staying connected with his teammates. “I would pace the sidelines, rooting for the defense,” he said. “I would be talking to guys all the time. I liked being involved.”

Andersen’s sideline techniques included breath control to decrease his pulse and heart rate. He’d press his tongue on the roof of his mouth, breathe in through the nose and out through the mouth, all to control his heart rate.

“The calmer and more focused you can make yourself, the better,” Andersen said.

He looked at the specific little four-yard patch of turf where he’d kick as his “workbench.” “Everything there was very rehearsed,” he said. “That didn’t change if they called a timeout. I’d step back from the fray, and recycle.”

Ah, yes. The inevitable time-out right before the snap. That had a crucial impact on one playoff game, as we’ll see in a moment. But does it work? According to the best kickers in the game: nah.

“You think you’re getting in my head?” Nedney laughed. “I’ve been in my head my whole life.”

“An opposing team calling a timeout is just delaying the inevitable,” Andersen said. “You can’t ice ice.”

Jan. 11, 1987, AFC championship: Broncos 20, Browns 20, OT

The Broncos’ sideline was discouraged, deflated. The Browns had scored, going up seven, and the ensuing kickoff had pinned Denver at its own two-yard line with 5:32 remaining. The weather was miserable, the Cleveland crowd was woofing, and all seemed lost … that is, until John Elway started what would forever be known as The Drive.

“You can feel that momentum shift,” Karlis said. “At first, the defense feels like they have the advantage. Then you get some first downs on them, and all of a sudden that emotion kicks in, to protect what you have, and you tend not to be as aggressive.”

Elway marched the Broncos down the field, aided in part by some phenomenal receptions, and at that point Karlis saw that he was going to be a crucial factor in this game, one way or another.

With 39 seconds left, Elway hit Mark Jackson to bring the Broncos within a point.

“I did laugh to myself that this would be a bad time to miss an extra point,” he said. He would be kicking at the end of the stadium where Cleveland’s Dawg Pound was located. That end of the field was littered with dog bones — somehow security had “missed” fans carrying in sacks of dog treats — and no opposing player could stand on that end of the field very long without getting pelted.

Amid the dog bones, Karlis made the kick, and that sent the game into overtime … but by then, the outcome was all but decided. Or, at least, the setup was.

“The Browns were so shell-shocked that we came back,” Karlis said. “John’s confidence in the offense was sky-high.” He took the Broncos down the field, in the opposite direction, setting up a 33-yard field goal.

That end of Cleveland Municipal Stadium didn’t have the Dawg Pound up close. Instead, there were dozens of yards of clear, open space between the goal post and the fans — space that would play a small but significant role in what was to come. That end of the field also was covered with sand, painted green and slathered right where Karlis would be kicking. Karlis’s holder, backup quarterback Gary Kubiak, coolly smoothed out the sand and looked at Karlis.

“After you make this,” he said, “I’m going to jump right on you.”

“Dude,” Karlis replied. “You’re way ahead of me.”

The ball was snapped, Kubiak took the hold, and Karlis strode forward into the sand. “It was like kicking out of a sand trap,” he says. “My plant foot slid toward the ball. The flight of the ball has a hook on it … which became highly controversial.”

Watching that kick, you can see the ball hook. The question is, did the hook come before or after it had gone through the goal?

“If you look at where those cameras are mounted, 100 yards away from the goalpost, you can’t really tell on camera where it crossed,” Karlis said. “I didn’t jump, I didn’t celebrate, I looked straight down the post … The referee under the post didn’t hesitate.”

Karlis turned to look for Kubiak, but — despite what he’d said before the kick — Kubiak was gone, off and running. Instead, Karlis leaped up onto linebacker Rick Dennison — who then fell on Karlis, collapsing him under a pile.

“I don’t know if I have ever had an emotional high like that,” Karlis said. “Ending up on the cover of Sports Illustrated … for a kid who was a late bloomer, didn’t start kicking until senior year of high school, walked on in college, it was pretty magic.”

Final score: Broncos 23, Browns 20

Jan. 11, 2003, AFC divisional playoffs: Titans 31, Steelers 31, OT

Kicking once in a crucial playoff moment is a wrenching thought. Twice? That’s just inhumane. But three times? Now we’re getting into the realm of absurdity.

The Titans had played the Steelers to a draw in the second week of the 2002 season playoffs, and here was Nedney in overtime, with a chance to end it all. He booted the ball, the kick went through the uprights, and an overzealous stadium pyrotechnics expert launched fireworks all over what was then known as Nissan Stadium. (You can see Nedney’s three kicks here.)

“It went on for what seemed like forever,” Nedney recalled. “I was looking at them thinking, ‘This is really cool. Anybody driving by on I-40 must think we just won.’”

There was just one problem for Tennessee: The Steelers had called timeout.

Forced to kick again, Nedney stepped back, re-set, strode forward again … and flat shanked the ball. The air went out of the stadium even as the haze of fireworks still hung in the air.

Years later, he admitted that he was already thinking about a celebration when he stepped into the re-kick. “I pulled it. It was the worst kick I ever had, just an ugly duck hook,” Nedney said. “I saw my entire career flash before my eyes.”

There was just one more problem, this one for Pittsburgh: The Steelers’ Dewayne Washington ran into Nedney as the ball was already on its way.

“Somebody hit me, and I’m thinking, ‘Do I go down?’ ” Nedney recalled. “It was fight or flight. I could have stood up there and took the blame, or I could have gone down and tried to give our team another shot at the Super Bowl.”

Nedney made his decision. He flopped like a puppet with cut strings, and that was enough to draw the attention of a referee. Flag, re-kick, and this time — on kick No. 3 — Nedney, his head clear, drilled the 26-yarder through. No flags, no timeouts, no more hope for the Steelers.

Pittsburgh was livid, from then-head coach Bill Cowher on down. “For a game to be decided on that call,” Cowher said at the time, “is ludicrous.”

Nedney stoked the fire with an ill-advised postgame quote. “He got a pretty good hit on me,” Nedney said, “but when I’m done playing ball, I might try acting.”

“That was a stupid-ass comment,” Nedney now says. “I learned a lot after that. Life has a way of humbling you.”

Final score: Titans 34, Steelers 31

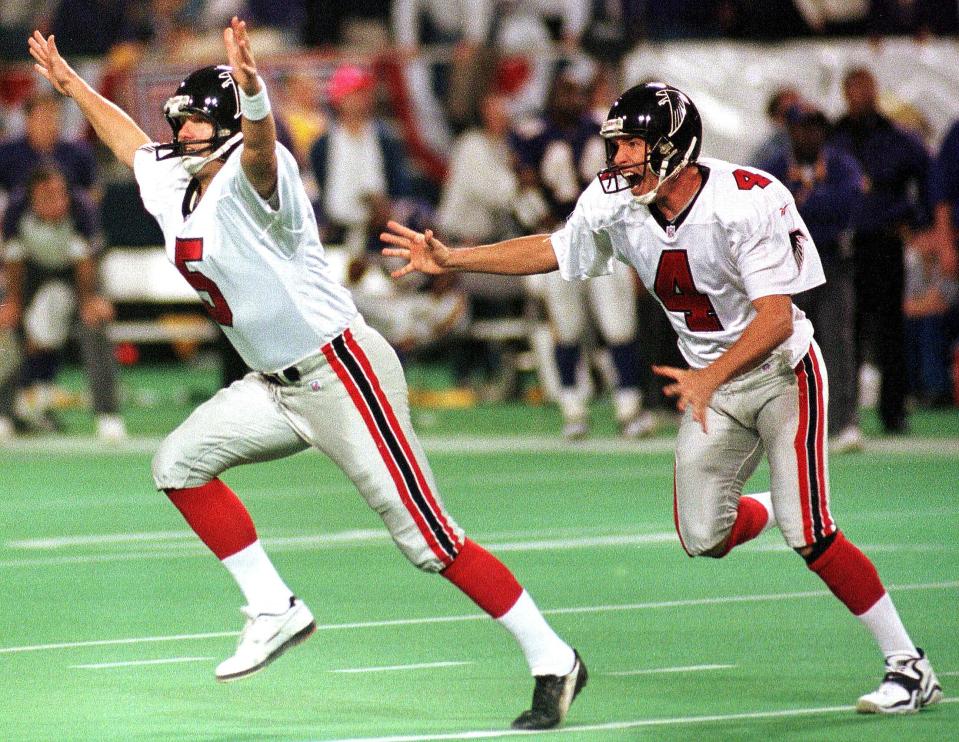

Jan. 17, 1999, NFC championship: Falcons 27, Vikings 27, OT

The Falcons were down seven, and Gary Anderson — who had been perfect all season for the Vikings — lined up for what would have been a decisive dagger. But against all odds, Anderson missed the 38-yarder … and the Falcons had new life.

Over on the Falcons’ sideline, Morten Andersen felt a touch bad for his counterpart — he knew well what it was like to miss a decisive field goal — but he knew the door wasn’t yet barred. The Falcons scored a touchdown, pushed the game into overtime, marched down to the Minnesota 38-yard line, and then called on Andersen — who at that moment was feeling a strong sense of déja vu.

“The night before, when I did my mental training, I wrote four scenarios,” he said. “The opening kickoff, a kick right before the half, a kick at the end of the game … and an overtime game winner from the 38-yard line, left hashmark.”

It was at that moment that he knew the Falcons were headed to the Super Bowl. “We were driving, we were inside my range, inside my wheelhouse,” he said. “When the skillset manages the task, there’s no pressure.”

And then Andersen noticed his teammates. He didn’t tell them what he already knew — that he had this. He trotted out to the field, set up exactly where he’d envisioned, and felt the crowd in his feet.

“The roar in the Metronome was the loudest I’ve ever been a part of,” Andersen recalled. “The floor was moving. It was kind of vacillating.” The timeout was coming — Andersen knew it — and then he settled in. The snap was perfect, the hold was true, and then ...

“I remember this slow-motion, warm feeling,” he said. “As soon as I put foot to ball, I turned. The goalpost could have been two feet wide, it was so dead-center.”

The silence was instant, the Metrodome going from triple-digit decibels to library-quiet. Andersen, meanwhile, lost his mind. “I went absolutely bonkers,” he laughed. “I was running like a [expletive] madman. I started getting chased, and I realized I’d better keep running or I was going to end up on the bottom of a pile, and it was going to hurt.”

The good news rolled on for Andersen. After the game, sitting on the bus, he got a call from his agent. After the requisite congratulations, Andersen’s agent said, “You don’t remember, do you?”

“Remember what?” Andersen said.

Turns out that when Andersen’s agent had negotiated his last contract, it included a clause that granted him a $300,000 bonus if he kicked the winning field goal in the NFC championship or the Super Bowl.

“I’m glad you’re telling me this now,” Andersen said, “and not before the game!”

Final score: Falcons 30, Vikings 27

The unfortunate coda to each of these stories is that in each instance, the team lost its next game. Maybe they used up all their mojo on those final drives, or maybe the odds just tilted away from them the next time around.

These days, those famous kicks are far in the past but never distant. Nedney works with local high schoolers and has a landscape business in Northern California, and he knows there are plenty of people in Pittsburgh who still haven’t forgiven him.

Andersen, a motivational speaker and a brand ambassador for VegasInsider.com, travels the world using his kicking background as grist for inspiration. “You earn the right to play the game at its highest level during the week,” he says, and he’s got a point.

Karlis, a senior director at CenturyLink in Denver, still hears about the kick, and not always from Broncos faithful. “Now and then,” he said, “a couple buddies of mine that are huge Browns fans tell me I ruined their childhood.”

More from Yahoo Sports