Sundance Winner ‘The Eternal Memory,’ Story Of Alzheimer’s And A Couple’s Bonds Of Love, Makes Berlin Film Festival Debut

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Doctor Zhivago, Casablanca, Amour. Over the decades, cinema has produced some fictional love stories of enduring beauty and resonance. But for sheer emotional force, even those classics may not rival the true love story told in The Eternal Memory.

Maite Alberdi’s documentary, which made its international premiere at the Berlin Film Festival, centers on the remarkable bond between a Chilean couple, the esteemed writer and journalist Augusto Góngora and his wife — an actress, academic, and Chile’s former Minister of Culture, Paulina Urrutia Fernández. They spent many joyous years together before Augusto was diagnosed, in 2014, with Alzheimer’s.

More from Deadline

The film begins with a scene shot in the couple’s bedroom in the middle of the night, after Augusto apparently has awoken. Smiling, he introduces himself to his wife. “I’m Augusto Góngora,” he says. “And who are you?” Patiently, lovingly, she replies her name is Pauli. And she explains, “I am a person who has come here to help you remember who Augusto Góngora was.”

Urrutia recorded the moment on a camera affixed to a tripod. “She shot like half of the film,” Alberdi tells Deadline. “I started shooting in 2018 and in 2020 when the [Covid] lockdown started, it was like, what are we going to do? I told Pauli, ‘I will send you a camera and you can shoot anything,’ but I never expected to get good material, really. And the first scene that I received, it’s the first scene of the film. It was like, I cannot believe it, because even if I were there, I could never shoot this in the middle of the night, in the bed. It was an intimacy that only they can shoot.”

When Góngora was first diagnosed, the couple shared the news publicly.

“I read that interview and it was really touching,” Alberdi recalls, adding that they spoke of wanting to continue their loving relationship no matter what might develop with his condition. “I was so moved.”

A public announcement was one thing, but agreeing to a documentary would involve a willingness to share their experience on another level.

“Paulina didn’t want do it. She was like, ‘No, I don’t want to expose this anymore,’” Alberdi says. But Urrutia’s thinking evolved and ultimately she decided “to open the doors of my own house to show my fragility. A record should exist.” Góngora concurred.

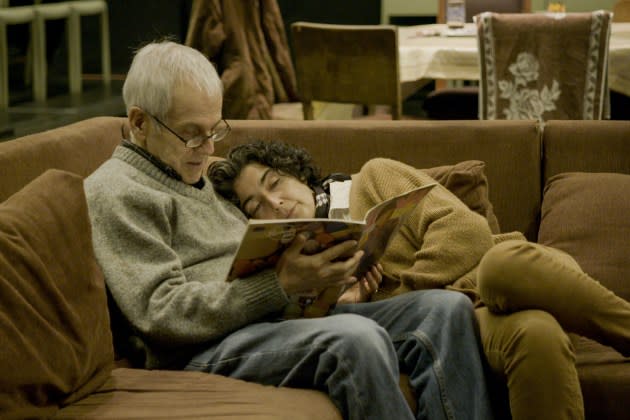

Alberdi, who earned an Oscar nomination for her previous documentary, The Mole Agent, filmed Paulina and Augusto as they went to her workplace together. With evident satisfaction, he joins Paulina on stage as she rehearses a play, participating in dances with his wife and the cast.

“She took him to her [work] life and it was good for him because he had a social life,” Alberdi says. “She took care of him, but also the people in the theater that were with her, everybody was helping. It was a collective, ideal situation for a caregiver not to have to isolate their [loved-one].”

Góngora displays warmth, humanity and sense of humor despite his condition. “I’m going to fight to the end,” he declares. “I love life.”

The outbreak of the pandemic, though, forced everyone in Chile into isolation, with particularly severe consequences for Paulina and Augusto.

“That’s why he would get worse so fast because he didn’t have therapy, he didn’t have a social life,” the director says. His rate of cognitive decline accelerated 12-fold, Paulina and her husband’s doctor concluded.

The documentary doesn’t gloss over the challenges posed by the degenerative illness, a reality that will be familiar to Alzheimer’s caregivers everywhere. As his disease worsened, Augusto would become anxious and confused more often. The film shows him talking to his reflection in a glass-paneled door, thinking someone else has joined them in their house. He thinks a large photograph of him and his wife that hangs on a wall is actually two real people watching him.

In moments of distress, he pleads, “Help me!” Another time, he demands of his wife, “Who are you?” “I’m Pauli,” she says gently. “No, you’re not!”

In one poignant sequence he is seen repeating to himself, “They love me, they love me,” as if dispel anxiety and reassure himself that people care about him. The toll on Pauli becomes evident in a scene where she cries after her husband has gone for a period of 12 hours without recognizing her. Somehow, the spell of confusion lifts, and he attempts to lovingly comfort her and dispel her fears.

“It’s a family issue,” Alberdi notes. “We always put the focus on the patients, but we don’t put the focus on the damage that [occurs] for the people that are with them.”

The Eternal Memory won the Grand Jury Prize for World Cinema Documentary at Sundance, where the film held its world premiere. In the midst of the festival it was acquired by MTV Documentary Films.

“It’s going to be premiering this year, but the distributor is [deciding on] the date,” Alberdi says. “I think in the middle of the year.”

Góngora co-authored a 1989 book called Chile: The Forgotten Memory, about political crimes of the Pinochet dictatorship, when opponents of the regime were “disappeared.” In the film, Paulina reads from his words: “Without memory, we don’t know who we are. Without memory, we wander, confused, not knowing where to go. Without memory, there is no identity.”

But in archive of a book launch event in ’89 that is shown in the film, Góngora explains that he defines memory more broadly than most, commenting, “[I]t’s not enough for memory reconstruction to be a merely rational act. Numbers and statistics aren’t enough. I think Chileans also need to rebuild our emotional memory.”

It is that kind of memory, beyond facts — memory embedded in emotional connection — that is reflected in the film.

“That speech [at the book launch] is the invitation of the film — to understand that there are some feelings that, yes, he cannot communicate verbally, he cannot express, he doesn’t remember and he cannot explain it, but the body [retains] something,” Alberdi observes. “And that for me was like an eternal memory, another understanding of memory.”

She adds, speaking of Pauli, “She said, ‘Memory, it’s constructed not alone, it’s constructed collectively. So, even if [Góngora] is losing his memory, I am his memory, like, we are a memory together.’”

Best of Deadline

Sign up for Deadline's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.