At Sundance, Behind the Exit of CEO Joana Vicente Looms a Larger Crisis

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The abrupt exit of Joana Vicente as CEO of the Sundance Institute in March — a mere two and a half years after taking the job — has film festival insiders reeling and a tight-lipped organization unwilling to talk about why.

But that may be because Vicente’s exit wasn’t triggered by a signature blow-up, a specific conflict or a particular programming failure, even though the Sundance Film Festival 2024 was smaller than in recent years, raised less money and sold fewer titles.

Multiple insiders told TheWrap that Vicente’s exit followed a failure to articulate a clear and compelling vision for the festival at a critical inflection point for independent film. While facing the complications of the COVID-19 pandemic, the CEO struggled to find common ground with an unwieldy board of directors, and was unable to nurture an internal culture of innovation, they said. Most damaging, she could not inspire donors at a time when independent film itself is being called into question.

“It wasn’t a good fit between her experience, her personal style, her abilities and that job,” said a former Sundance executive. “Sundance is an idea, and it is holding up a space in the sector that is under incredible duress.”

The problem isn’t the availability of funding, said the executive. Sundance remains beloved, but donors need a reason to invest. “There’s a massive amount of funding circling that organization, but they need vision. Not only from the CEO, but from the team. You have to paint a picture of what is happening. That’s not something she was good at.”

A person familiar with the board’s thinking said Vicente did a “lovely” job while facing difficult headwinds, noting that the Institute underestimated the impact of COVID, the loss of revenue from in-person festival ticket sales and the anxiety of donors. But they also noted that it was tough to galvanize a culture over Zoom meetings.

A third person familiar with the organization cited conflicts among the programming staff, going back to a dispute over the documentary “Jihad Rehab” in 2022, which saw the director accused of being Islamophobic and the Sundance Institute accused of betraying her after it disavowed the film a month after it played the festival.

“She seemed in over her head,” this person said of Vicente.

A Sundance executive disputed that Vicente’s leadership was lacking, noting that she worked to break down silos internally and unite the culture. But the executive did acknowledge that independent film is in “uncharted waters” and in a letter to Park City officials in September, Vicente herself noted “several years of declining revenue…that we still have not recovered from.”

Vicente declined to comment for this story, as did a spokeswoman for Sundance.

As for those “uncharted waters,” the crisis facing Sundance goes hand in hand with the challenges facing independent film as the arthouse business shrinks and streamers seek more mainstream fare.

One leading producer lamented the loss of in-person bidding wars in the hallways of Park City hotels, and with them the fancy gifting suites for talent and their posses, offering everything from parkas to snow boots to vacations, that used to clog Main Street.

“They have to upgrade the whole event in my opinion,” said the producer, who attends Sundance every year but finds the status quo frustrating. “They have made it indie niche.”

Money troubles

Major festivals have experienced turbulence in recent years.

The Berlinale Film Festival pushed out its well-respected artistic director Carlo Chatrian last year; in response 200 filmmakers signed a petition requesting his reinstatement (that didn’t happen). The Toronto Film Festival lost its longtime patron, Bell Canada, after a 28-year relationship, last August. And the upcoming Hot Docs film festival in Canada was plunged into chaos in March after 10 programmers quit, alleging a “toxic workplace.” Artistic director Hussain Currimbhoy also left for what he said were “personal reasons.”

The programmer exodus at Hot Docs followed a March 8 statement by President Marie Nelson saying the organization faced a cash crisis. “We are currently facing a significant operational deficit that threatens our long-term sustainability,” Nelson said. “While we’re already seeing positive signs of recovery as audiences both old and new are returning to the cinema, and while we’ve taken steps to reduce our overhead without impacting our core programming, we are quickly losing runway and urgently need direct support to ensure our future viability.”

As the granddaddy of independent film festivals founded by Robert Redford in 1980, you might think Sundance would be an exception.

It is not.

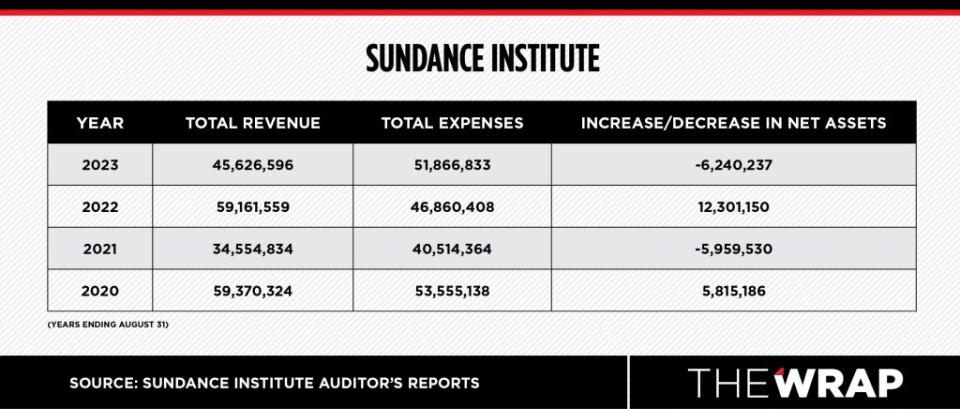

According to available audited financial filings, the festival has lost money in two of the last three years for which there is data. It lost $6 million in 2021 after total revenue dropped to a scary $34,554,834. Things picked up again in 2022, when Sundance reported $12 million in profit. But in the organization’s fiscal year 2023, which ends in August, it reported losses of $6.2 million thanks to revenues of $45,626,596 against costs of nearly $52 million. (The year 2024 is not yet available.)

According to multiple insiders, the biggest financial blow came in 2022, when the festival had planned to return in person after a brutal year of COVID, only for the Omicron strain in the winter of 2021 to force Sundance to pivot to a remote-only version.

Caught off guard, Sundance was ill-equipped to maximize revenue from a digital-only platform, even though that platform, created in 2021, had opened up the festival to a broader and younger audience than in the past.

“The festival got cancelled at the last minute,” said the former Sundance executive. “They did it digitally, but they hadn’t invested in marketing and sales for digital. So those parts of revenue needed more ramp, because they were counting on the live [portion].”

Since then, this person said, budgets have been cut, including some Sundance lab programs, but there has been a paucity of new ideas to drive investment from donors.

Two individuals told TheWrap that the festival has missed its donor targets in the last year. The institute responded that there aren’t firm donor targets.

Still, the audited financial statements reflect that “contribution revenue” went from a total of $47 million in 2022 to $32 million in 2023, with the largest category drops coming from Foundations and Government.

The ecosystem has changed. The festival doesn’t exist as a catalyst for sales.

a current Sundance executive

But the larger context of these financial issues is the crisis facing independent film as a whole. Sundance 2024 only accepted 83 feature films, compared to more than 100 the year before, a result, many believe, of the double strikes that crippled Hollywood in 2023. (It may also have been due to Sundance having fewer venues to screen movies.)

A lack of sufficient quality films in the pipeline was surely an offshoot of the strike, but also a likely outcome of the shriveling marketplace for them to be sold. It is common for only a fraction of the films that appear at Sundance to be sold to distributors, but as the costs of producing a film have dropped, the appetite by streamers seems to have dropped to near zero.

This year TheWrap called the Sundance marketplace “sluggish” after reporting that the streamers made clear they were not interested in edgy, independent filmmaking. Perhaps a dozen films were bought, but very few by the large streamers. Instead, Focus Features bought the crowd-pleasing “Didi,” which opens this summer, among a slew of purchases by arthouse distributors like Neon, A24 and Sony Classics. Netflix acquired worldwide rights to the horror film “It’s What’s Inside” for $17 million.

The winner of the top prize at Sundance, “In the Summers,” about two sisters and their relationship with loving but volatile father during their yearly summer visits to his home in Las Cruces, New Mexico, does not have distribution.

It’s a far cry from 2021, when Apple paid $25 million for the crowd-pleasing Sundance hit “CODA” and took it all the way to the Oscar for Best Picture. In 2023 Netflix paid $20 million for the psychosexual thriller “Fair Play,” which did not make the same impact.

Some producers blame Sundance for programming films that aren’t mainstream in their appeal. “They need a major rethink on the programming front,” said the leading producer who declined to use their name. “So few deals — nothing big showed, and the indie distribution business is already suffering.”

This producer noted that the big buyers no longer needed to come in person, as the films are available online. “They need to add more commercial films and stop this lunacy of putting the movie online which lets buyers not have to come and creates no bidding wars which was really the excitement of being there.”

Regardless of the reason, the distribution hole impacts the entire ecosystem of independent film — from producers to filmmakers to distributors. “If you expect Sundance to continue to be a place where films get bought at an 85% buy rate for a lot of money, you haven’t talked to those streamers,” said the former Sundance executive. “They are not interested in independent films.”

Said a current Sundance executive: “The ecosystem has changed. The festival doesn’t exist as a catalyst for sales.”

Meanwhile, Sundance’s ability to continue to hold the festival in Park City is also up in the air. The contract with Park City expires in 2026, and Sundance has been looking at alternatives as hard costs for the festival continue to rise, as has housing during the festival for attendees and filmmakers, making the festival out of reach for the people it is made for.

In September, Sundance asked Park City officials to extend the contract renewal deadline from March 1 to October of this year. “We have new executive leadership, we have had several years of declining revenue triggered by a global pandemic that we have still not recovered from,” Vicente wrote in a letter to the mayor and city council. “There are many uncertainties but also great possibilities this moment presents.”

Woke tensions

Far left-driven political turmoil has beset media outlets and arts organizations in recent years, and it hit Sundance hard in 2022, just after Vicente took over as CEO following her exit as co-head of the Toronto International Film Festival.

In January 2022, Vicente had been CEO for only three months when a documentary then-called “Jihad Rehab” (the title was later changed to “The UnRedacted”) screened in competition at the festival, held online that year due to COVID.

The film, directed by Meg Smaker, is about a rehabilitation center for Islamist jihadis in Saudi Arabia. Smaker had learned to speak Arabic and spent five years convincing the Saudi government to allow her access to the center to make the film. But even before it premiered at Sundance to strong reviews, it had been attacked on social media by a group Muslim filmmakers (the majority of whom hadn’t yet seen it), who wrote Sundance to object that the film took up space that could have gone to Muslim, and/or ‘MENASA’ (Middle East, North Africa and South Asia) filmmakers to tell non-terrorism related stories, and for allegedly “endangering its subjects.”

Two Sundance Institute staffers later resigned over the film, after which Vicente and festival director Tabitha Jackson issued a statement apologizing for it, saying, “In this case it is clear that the showing of this film hurt members of our community — in particular, individuals from Muslim and MENASA communities — and for that we are deeply sorry.”

Smaker, who found her film pulled from every other film festival after the Sundance release, felt betrayed. Programmers internally questioned the process. Meanwhile, almost no one had actually seen the film. The board, which includes prominent Hollywood figures like former Disney production chief Sean Bailey and producer Jason Blum, was dismayed by the negative attention.

“They didn’t expect to be hit so hard,” said the former executive, referring to the board. “They didn’t know who to believe in terms of the situation. They were seeing letters from hundreds of artists saying Sundance has betrayed us by playing this (movie)… And programmers saying, ‘We stand by it.’ The board didn’t know what to do.”

It was an early black mark on Vicente’s leadership. Jackson exited Sundance as festival director within a few months. From there, Vicente had to work to regain the confidence of her team and the board. Fast forward two years later and what was described as “long, hard conversations” with the board, she resigned.

****

Whether or not Vicente was the right fit, the Sundance Film Festival will need to find a way to regroup and reimagine. Some people interviewed by TheWrap feel that Vicente’s replacement, Amanda Kelso, now acting CEO, is the right choice. Kelso has been on the board for four years, and was involved in the transition to an online festival during the early days of the pandemic.

Several said that identifying a vision and reinvigorating the mission of the festival was the most important priority.

As a programmer from another festival observed: “Festivals run on passion, the passion of the audience and the passion of the festival team. Once you crack that, once you break it open and the team can see you really don’t think they are important at all, it’s over.”

Steve Pond and Kristen Lopez contributed to this article.

The post At Sundance, Behind the Exit of CEO Joana Vicente Looms a Larger Crisis appeared first on TheWrap.