‘Sugar’ Is Not How American TV Usually Gets Made

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

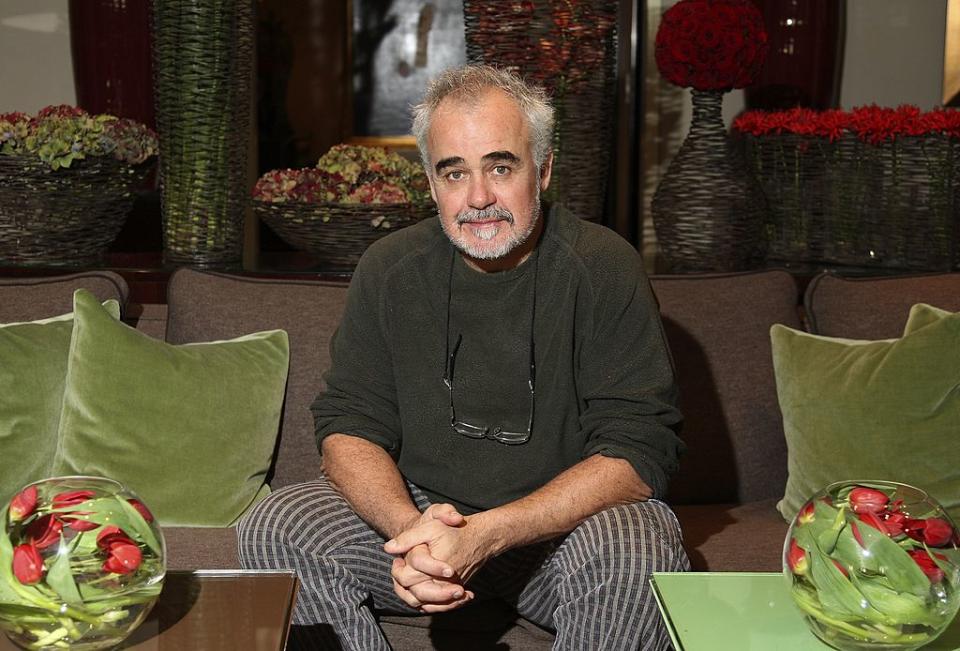

In Hollywood, director Fernando Meirelles is known for critically acclaimed films like “City of God” and “The Constant Gardner.” His TV work had been confined to Brazil, which, he discovered while shooting the Apple TV+ series “Sugar,” was nothing like American TV production.

“My first impression [was] the size, the scale of the whole thing, it’s a big circus,” Meirelles told IndieWire. “You’re tied into this big machine, and you’re piloting the machine, but the machine is also taking you. It’s an interesting experience, much different from what I was used to, but I really enjoyed it.”

More from IndieWire

Bowen Yang Says His Body Shut Down During 'Wicked' Production: I Couldn't 'Lift an Arm'

'The Big Cigar' Review: André Holland Is Excellent in an Erratic Biopic

Meirelles description makes it sound like he was an important cog in the big wheel of TV production, which, of course, is common for directors who enjoy more autonomy of smaller films. Except “Sugar” does not move, look, or feel like anything on American TV. The coverage and cutting patterns are anything but conventional. The scripts lean into neo-noir tropes, but the filmmaking is more interested in the metaphysical, establishing a point-of-view that is familiar to those who know Meirelles’ films.

But the director is clear: This is not a Fernando Meirelles joint. Not only is “Sugar” the brainchild of writer and showrunner Mark Protosevich, but Meirelles’ visual storytelling is not his alone.

“I’m only one person, but actually, the direction is three [people]; it’s really [cinematographer] César [Charlone], [editor Fernando] Stutz, and myself,” said Meirelles.

This is not a noted international auteur being humble, shining a light on long-time collaborators. Meirelles’ direction is process-dependent, and it’s an approach in which the visual storytelling is guided in equal parts by each of the Brazilian collaborators.

“We really work as one,” said Meirelles. “If I can’t take César and Fernando, I won’t be able to [do the project], that was my only condition.”

Stutz compares the three to improv musicians who have been playing together for a while to describe how they work. Meirelles used that jazz analogy when he met with Colin Farrell. In addition to being the reason the show got greenlit, Farrell is the series’ executive producer and star, who is in virtually every scene. Meirellees needed the star’s buy-in to his way of filmmaking, which Stutz said can seem “unprofessional.”

“We spoke for one hour and a half in our first call and it was like we were best friends,” said Meirelles. “I love the way Colin works; he likes to improvise, and how he puts himself into the project.”

Meirelles said yes to the project because of Farrell. After their meeting, he not only believed he had the star’s buy-in, but he also believed the trio could become a quartet.

“It’s very hard to find someone that embraces our chaotic way of creating,” said Stutz. “Colin is unique. He’s open to all the craziness, because I know this is not the way the Hollywood industry works. There’s no time to experiment.”

Meirelles’ approach to directing is part theater, playing a scene from beginning to end each time. The action is not split up and staged into camera setups; rather, Charlone’s approach to shooting is to document it with two to three cameras.

“We have developed what I would call a documentary style,” said Charlone. “We leave the actors very free to move around, my crew does not put [down] any marks, the actors just move around and we follow them with the camera.”

After each take, Charlone completely changes the cameras’ angle and movement. Meirelles said that after two hours of shooting, he will often have 15 to 16 different angles, each master of the whole scene. This approach often leaves them an hour or two ahead of schedule, which just encourages more experimentation.

“We spoke about wanting it to feel alive, it could change direction at any moment,” said Farrell, who got so into Meirelle’s way of filmmaking that he’d ask for multiple takes back-to-back without cutting, significantly altering his performance each time. “And that was represented by the camera operation and the framing. César operates a lot and would be getting right in [there], kind of verite style, moving around. It kept everything really organic and alive.”

While they don’t shot list, Charlone and Meirelles have a deep and detailed prep process. Going through every script page by page, the director pinpoints for the cinematographer the important emotion and perspective he wants to elicit from each scene. How that is captured is something the DP finds on set. Charlone grabs a number of different and bold angles himself, often with an iPhone.

“The best part about doing an Apple series is they gave me the best iPhones they could,” said Charlone, who gets giddy talking about a $1,300 piece of consumer hardware on a shoot that relied mostly on Sony Venice camera packages that cost 100 times that. The cinematographer described a scene between Sugar and Melanie (Amy Ryan) talking on a couch as an example of how he used the device on which you’re likely reading this article. “I would first shoot an establishing shot with the main camera, but then I would go close in between them and get a tighter details: lips, his eyes, I could go a little bit deeper and tighter with the iPhone and not affect the performance.”

Charlone liked to tell his crew, “Today is a shoot day,” which is code that they would always be shooting. The cinematographer has his iPhone rolling even as they travel between locations, grabbing glimpses of Farrell looking out the window or the way the light reflects on the ceiling.

“I have a joke I always repeat, that for me it’s not about quality, it’s about quantity,” said Charlone. “The feeling you have on set is often wrong, the real feeling is settling down and looking at the screen, watching the edited movie.”

It’s unusual to hear such a talented cinematographer talk this way, but to Charlone’s way of thinking the quality comes from editing, and the quality of editing is dependent on the quantity of how many viable options he gives the editor. Meirelles is even more direct about it, “I make my films in the editing room.”

There’s a reason TV is not shot to rely on more set coverage: The amount of footage and different options Stutz has to weed through is overwhelming. To start, he often begins with Charlone’s “crazy” camera.

“I start by looking through César’s lenses because it’s the way he moves through the scene,” said Stutz. “He comes from a documentary background and he is also a director, so when he operates the camera I’m always interested where he’s going, what he’s looking at, and then from there, start to build the sequence.”

For cutting a scene, Stutz ultimately relies more on standard masters, but he is always surprised how many of Charlone’s iPhone shots find their way into scenes. They are often repurposed in ways that are out of context of how they were intended but add the perfect texture, feel, or beat to a moment.

“I’m grateful to Fernando Stutz, he understands me very well,” said Charlone, who stays away from the editing room entirely and is always anxious to see the final cut like the project’s most impatient fan, delighting how the different moments he collected are put to use.

While Charlone’s background is nonfiction, Stutz is a student of experimental film and, when working on commercial projects, is interested in how to bring experimental and formal devices to pop culture. The intercutting of Hollywood films to reflect Sugar’s thought process is a perfect example. And on “Sugar,” Meirelles was looking to experiment. The director was desperate to avoid the predictable rhythms of shot-reverse-shot that are common in long dialogue scenes on TV, so he’d shoot over both shoulders in various takes.

“The first thing we learn in film school is never jump the eyeline,” said Meirelles. “I tried on purpose to jump the eyeline just to test [it out], and it really worked. It gives a dynamic to the scene.”

Meirelles and Stutz are in agreement, though; the biggest thing is that all of Charlone’s different options and interpretations allowed them to more fully establish and enter Sugar’s perspective.

“I wasn’t really very interested in Olivia,” said Meirelles, referring to the missing girl Sugar has been hired to find. “I was interested in Sugar, he was the mystery I cared about. And [the footage options] make a difference when some of the scenes were more focused on other characters, but in the cutting room, we really made the whole show his point of view.”

Considering the Episode 6 spoiler/twist, Sugar’s subjectivity is not obvious to pinpoint. One of the things Protosevich and Farrell talked quite a bit about Sugar’s outsider perspective, that almost immigrant sense of observing another culture they wished to be part of but could never fully enter.

“In speaking to Fernando and very quickly realizing that although he has visited L.A. many times through the years, he’s never set down roots here,” said Farrell. “He came at it with child’s eyes, he wanted to catch as much on the fly as much as he could. He wanted to shoot the city the way he found it and the way he was discovering it.”

Meirelles, Charlone, and Stutz all talked about how they wanted to end episodes with subtle moments of Sugar’s and the audience’s focus drifting elsewhere. Charlone always supplied shots of the moon, the light dancing on the ceiling, Farrell looking off to the distance.

Farrell himself got in on the experimentation of entering a certain metaphysical space of how the camera captured his perspective driving around Los Angeles.

“We were shooting Monday to Friday, and Colin came up and said, ‘César, would you mind coming this weekend with me in a car, grab some scenes of me driving with the iPhone,’” recalled Charlone. “Just the two of us, we just drove around and grabbed some images of what calls Sugar’s attention. It was the camera interpreting the acting, helping the acting, and this was 100 percent his idea. I loved it.”

The genuine admiration the three Brazilian filmmakers grew to have for Farrell went far beyond the normal smoke-blowing you get in press interviews. Their faces lit up when discussing the actor. Meirelles had tried to get Apple to hire some of his favorite Brazilian actors who were used to working with him, but legal issues got in the way. Yet it is clear he relished finding a compadre in the Hollywood star, telling IndieWire he was actively looking for a film project to collaborate with Farrell on, along with Stutz and Charlone, of course.

Best of IndieWire

The 13 Best Thrillers Streaming on Netflix in May, from 'Fair Play' to 'Emily the Criminal'

The Best Father and Son Films: 'The Tree of Life,' 'The Lion King,' and More

The 10 Best Teen Rebellion Films: 'Pump Up the Volume,' 'Heathers,' and More

Sign up for Indiewire's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.