BIPOC Writers Say Their Struggle for Equity Continues After the WGA Strike Ends

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

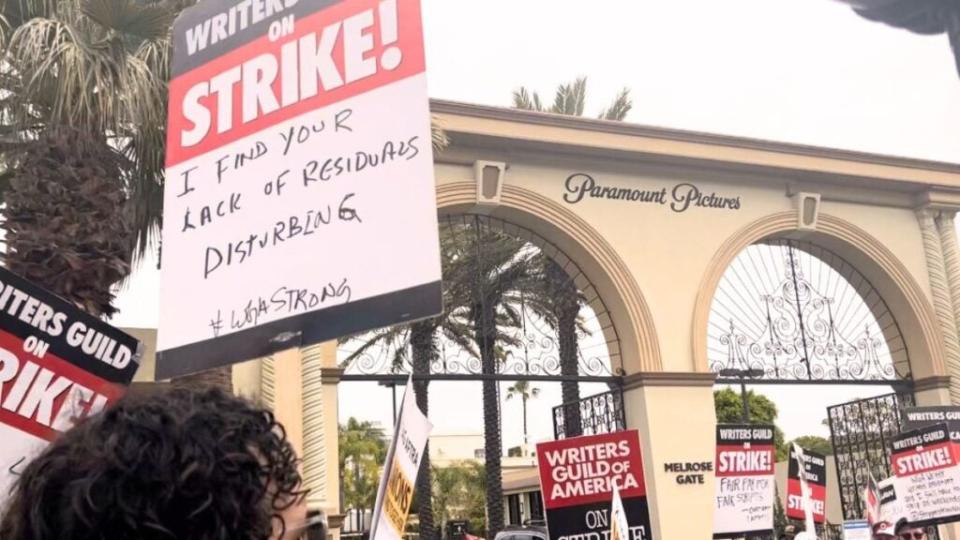

Unity has been a watchword throughout the WGA strike, as writers fight for increased wages in the face of shortened TV seasons, the curbing of mini-rooms they say have been abused by studios and protection against AI. But while Hollywood writers and other unions are aligned in the fight, writers of color stress that even if all of the Writers Guild’s demands are met, they’ll still be struggling for equitable opportunities, representation and upward mobility in the industry.

“I have to speak up, even when the strike is over,” said writer Joel Boyd (“History of Swear Words”) in a recent interview with TheWrap. Boyd, who identifies as Black, joined dozens of his fellow writers at the picket lines in front of Paramount’s studio and pointed out how the amount of racial diversity seen at picket lines is indicative of the lack of diversity in writer’s rooms today.

“I think it’s also [writers of color] fighting to have the energy to be our authentic selves — even around some of these picket lines where people don’t look like you,” Boyd said. “When the strike is over we have to enter back into spaces where I may be the only one who looks like me or has my voice.”

Per the WGA West’s latest Inclusion & Equity Report, the percentage of BIPOC writers has increased over the last 10 years from 13.6% of employed writers to 37% in 2020. However, white women (25.9%) and white men (37.4%) still make up the largest share of TV employment. Black writers make up 15% of the TV writers, Latino writers make up 5.9%, Asian/South Asian/Pacific Islanders make up 6.4% and Native Americans have the lowest percentage of representation in the writers’ room with only 1%.

While the numbers have relatively improved, BIPOC writers say there’s a disconnect between TV executives and understanding the importance of not only having people of color represented on screen but behind it as well.

“I’ve heard from some executives that they’re only going to hire an Asian American [writer] if there’s an Asian actor on the show,” Brian Shin (“Good Trouble”), who identifies as Asian, told TheWrap. “I’m not saying this is across the board, but that’s the general kind of consensus, is that unless there’s an Asian actor on the show, there’s no reason to hire an Asian writer. That’s something I would like to see go away.”

Shin explained that even having more than one person of the same racial background would help provide different perspectives for POC characters.

“I was always the only Asian person in there, and it creates a situation where you’re like, ‘Well, everybody’s going to turn to me when there’s an Asian character,’ so you have this pressure to speak for everybody,” Shin said. “I’d love for there to be conflicting opinions from multiple Asian American writers in the same room. We have different experiences in the (Asian) diaspora.”

Grouping people of color’s unique backgrounds into broad generalizations is another sub-layer of issues BIPOC writers face in the room. Lauren Goodman (“Snowfall”), who identifies as Black/African American, said it starts with executives understanding and valuing POC stories.

“I came up in a room where the story was about crime, but Black lives are more than just crime dramas,” Goodman said. “There are family dramas, there are historical dramas, there are period dramas. Hopefully, we’ll have a chance to tell all those stories that reflect all of our lives.”

Allison Lee, who identifies as Korean American, explained that efforts to bring forth more racial diversity are sometimes side-swiped by Hollywood studios’ claim TV is already oversaturated with POC-centered stories.

“There’s also pushback like, ‘Oh, I already have Black Americans or, ‘I already have a Korean American story. So we’re not going to take your story,'” Lee said. We’re asking to be on screen at the same level as all the characters we grew up with, which were white. We want audiences to grow up seeing themselves in the shoes of characters that look like us.”

Even when people of color are granted access to the writer’s room, they’re still confronting barriers they say their white counterparts don’t have to face, like repeating a cycle of lower-level writing positions that don’t afford them the opportunity to grow their skillset or develop their careers.

Also Read:

Screenwriters Worry That Film Concerns Are Taking a Back Seat in Hollywood Writers’ Strike

“If you’re a staff writer on one show, after you’re done with that show, oftentimes you would get a bump — usually this happens for white writers,” said Nasser Samara, who identifies as a queer person of Palestinian and Mexican descent. “But for whatever reason, writers of color will often have to repeat the lower levels — sometimes twice, three, even four times. So what happens is these writers are not getting paid as well as they could because they are having to repeat. The jump in pay from, let’s say a staff writer to a story writer, is quite significant.”

Even the existence of the mini-rooms and the limited number of opportunities writers are given to go on set — two factors the WGA is fighting to make more equitable in their negotiations with the studios — disproportionately impact writers of color.

“If you only have say four or five writers you can hire (for a mini-room), you’re going to want to hire writers with more experience. And oftentimes writers with more experience are not writers of color because we have been having to repeat levels far too many times,” Samara said. “If you’re a writer of color just breaking into the industry and you’re now on a show, because of the pandemic and because of certain costs, they’re not getting the opportunities to go (on set), which means how else are you supposed to graduate and get higher pay?”

Also Read:

Paramount TV Studios Suspends Overall Deal With Justin Simien’s Culture Machine Amid Writers’ Strike

Writers who haven’t even gotten into the WGA yet say they’re already being affected by these types of issues. Cydney Fisher and Neima Patterson, who both identify as Black/African American, completed their master’s programs at the University of Southern California in 2018. Five years later, the two are still struggling to move out of writer’s assistant positions while going through several writing fellowships.

“I’m an assistant again after a year of trying to get a writer job” despite having management that represents her, as does Patterson, Fisher said. “I would love for us to not have to do like 50 fellowships just to get into a room.”

Patterson said fellowships, which are programs that have been created to boost (usually emerging) TV writers’ careers through mentorship opportunities and other resources in the TV and film industry, are good at the beginning stages of a writer’s career, but she argues they should eventually yield a job opportunity.

“It kind of feels a little discouraging and saddening, but I’m showing up because of my future,” Patterson said. “When I do get that opportunity, what does my future self want to see? How can things change so that when I’m in a position of power I’m able to train people under me in a better way and bring them up in a way where they can really grow?”

As the WGA closed out its first month of the strike, Sam Chanse (“The Good Doctor”), who identifies as a woman of Asian descent, said the industry has a much longer road to go in reaching racial equity in the writer’s room, and until that day comes, the careers of BIPOC writers will continue to suffer.

“Writers are much more vulnerable in terms of being involved in what we’re striking for, security and the protections and all the reasonable demands that are on the table,” Chanse said. “Those are all especially necessary for a more vulnerable community. When you’re in a community that’s less represented… It’s changing, but I think we’re still a long way off from not feeling like it’s a burden to represent that perspective.”

TheWrap reached out to the WGA and the AMPTP. The AMPTP declined to comment, and the WGA did not return our request for comment.

Click here for all of TheWrap’s WGA strike coverage.

Also Read:

‘We’ve Been Here Before': Studios and Writers Got Unexpected Preparation for a Long Strike