‘Streets of Fire’ Should Have Been the Biggest Rock Musical of the ’80s

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

No one was afraid of cinematic excess in the ’80s, and nothing says “cinematic excess” quite as perfectly as the rock musical, a sub-genre that took on all sorts of (rockin’ and rollin’ and just plain bitchin’) shapes in the decade that birthed everything from “Purple Rain” to “Flashdance” and “The Blues Brothers.”

Buried amongst a decade rife with musicals, rock jams, and the frequent intersection of the two is Walter Hill’s raucous “Streets of Fire,” an intensely creative rock musical fantasy filled with fantastic visuals and even better songs. It’s about as cool a film as anyone could ever hope to see, no matter the decade.

More from IndieWire

When it was released in the summer of 1984, the film was a box office bust: it made just $8 million on its $14.5 million budget, scuppering plans for an official trilogy, ultimately landing young star Diane Lane a Razzie nom (vile!), and sending Hill straight back into more bankable filmmaking (his follow-up feature was “Brewster’s Millions,” the seventh film iteration of the George Barr McCutcheon novel). Arriving in theaters on the heels of massive, enduring hits like “Spinal Tap” and “Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom” (and on the same day as “Star Trek III: The Search for Spock”), this undefinable — when is it? where is it? who is in it? — gem simply couldn’t compete with the big dogs.

But in recent years, the film has enjoyed a very well-deserved reconsideration, bolstered for all the same reasons that confused initial movie-goers: it’s intensely unique, a film rooted in the kind of unbridled creativity and cinematic excess that’s so rare at the multiplex these days. In a time when the movies are so fearful of failure, so intent on sticking to formula, “Streets of Fire” is intoxicating precisely because it refuses to do anything but its own thing.

When the film was made available to stream on Netflix in the summer of 2021 (a time when films like “Black Widow,” “F9,” and “A Quiet Place Part II” dominated the box office), suddenly it seemed that everyone was watching it (a general feeling I mostly gleaned from my Twitter feed and Letterboxd mutuals, i.e. Big Film Twitter). In 2022, the Museum of the Moving Image programmed it as part of the museum’s vaunted See It Big! 70mm summer series, a high designation it absolutely deserved, and just one step in a long road to reorienting the film as a classic of the era and genre.

Few films garner as hearty and enthusiastic a recommendation from me than “Streets of Fire,” mostly because the film is so stuffed with wild elements that it’s nearly impossible to find at least one bit that doesn’t appeal to someone. Do you like: Jim Steinman jams, handsome men, beautiful women, Rick Moranis being a jerk like you’ve never seen before and likely never will again, a baby-faced Willem Dafoe in leather coveralls, huge motorcycles, ripping flamethrowers, Amy Madigan being a mouthy sidekick, and the single most unexpected weapon to appear in any film of the decade?

It’s cliched to say a film has something for everyone, but “Streets of Fire” has something for everyone. It just took a few decades for everyone to catch up. Even I, an ’80s obsessive raised on the minor-level hits that played after school on TBS and TNT, didn’t get hip to its charms until about three years ago.

Initially conceived on the set of his 1982 Paramount hit “48 Hrs.,” the film is more tonally and stylistically in line with Hill’s 1979 comic book adaptation “The Warriors,” which similarly followed wild young adults as they careen through city life. While “The Warriors” is rooted in the milieu of late-’70s New York City, as its titular street gang makes their way from Coney Island all the way up to tippy-top of The Bronx (and back again), “Streets of Fire” is specifically set in a time and place literally built to be unspecific.

It’s nowhere. It’s everywhere. Mostly, it’s a feeling.

A pair of opening title cards let us know all we need to: the film is a “rock & roll fable” and it takes place in “another time, another place.” Imagine if the look and feel (and fashion!) of the ‘50s and the ‘80s somehow melded, and was then transplanted into all of New York City’s boroughs, with a generous streak of downtown Chicago thrown in for good measure. No one under the age of 30 appears in the film. It’s by no means a “high school” film, though Hill’s screenplay hits the same beats and mines the same character elements to form his fantastical world.

Our hero is Tom Cody (Michael Paré, fresh off his turn in “Eddie and the Cruisers” and seemingly perfect for a role Hill predicted would turn its star into a major Hollywood name; it did not), a gruff ex-solider of few words but many glowering looks, who returns home to his Brooklyn-ish city “district” Richmond after a terrible crime shakes the (again, very young) community. Before Tom headed off to war (a conflict whose details remain intriguingly vague, even after we meet another ex-soldier), he was involved with the gorgeous Ellen Aim (Diane Lane, who was just 18 when she took the role, fresh off her Francis Ford Coppola two-fer), who has recently become a rising pop star.

Ellen’s hometown concert in the Richmond opens the film, a vibrant, heart-pumping affair that everyone in town is attending. Elle and her band, The Attackers, cook, bolstered by those Jim Steinman jams (you don’t have to be a music wonk to recognize how much they sound like the world’s best Meatloaf songs that the Loaf never sang) and Lane’s incredible stage presence. So far, so cool, an electric mash-up of the ’50s and ’80s by way of fashion (greasers mingle with Valley Girls) and music that starts the film off on a truly high note. And then…

A group of motorcycle toughs descend on the show, their obvious leader just barely obscured in the gauzy darkness of the audience, until he’s revealed in both chilling and deeply cool style: it’s a very young Willem Dafoe, baby-faced but somehow also nefarious. His Raven springs forward, as do his heavies the Bombers, and they do something insane: they take Ellen, whisking her off-stage and on to a motorcycle, zooming her off to their own district, the gritty Battery.

Really, only Tom Cody could save her, and when Tom’s younger sister Reva (“The Warriors” co-star Deborah Van Valkenburgh) writes Tom a letter begging for his help, his inherent sense of justice and his lingering feelings for Ellen leave him no choice.

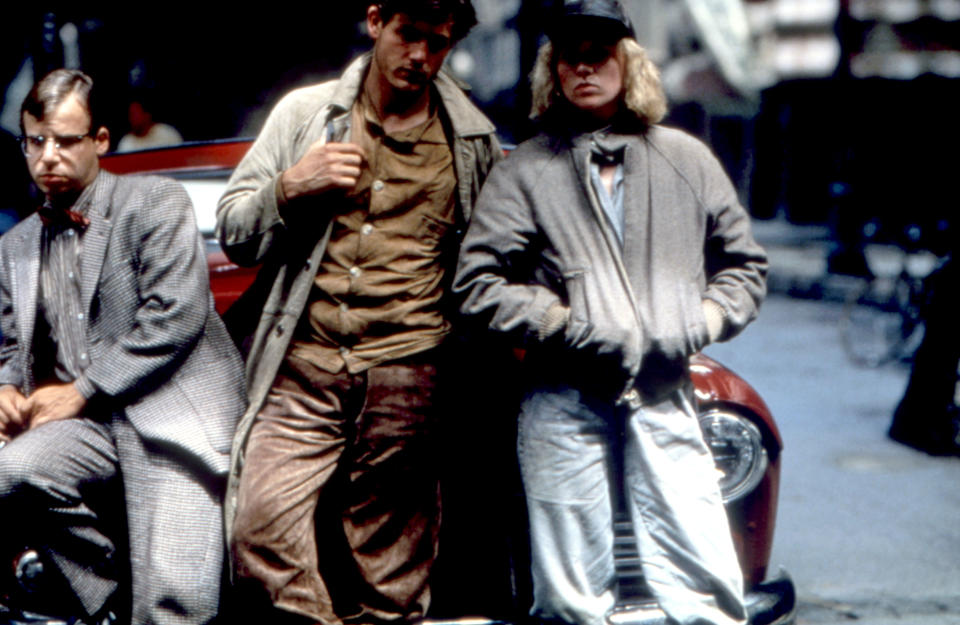

When Tom arrives back in the Richmond — predictably dashing, unnervingly stone-faced — he soon meets up with friends both old (a very young Bill Paxton as a goofy bartender) and new (Madigan as McCoy, a former solider looking for a job, and Moranis as Ellen’s venomous manager and would-be boyfriend Billy Fish). Tom, McCoy, and Billy Fish eventually team up and alight for the Battery, with only the vaguest notion of how to get Ellen back (read: blow stuff up?).

It’s a thin storyline, but it’s executed in a way that can only be described in one word: cool. It’s so fucking cool. There’s no slack here, just an all-bangers-no-skips soundtrack (Stevie Nicks’ “Sorcerer” and Ry Cooder’s “Hold That Snake”? two original Steinmans? a doo-wop spin on “I Can Dream About You”??), a prodigious amount of fire and firepower, and a cast so stacked that appearances by E.G. Daily and Robert Townsend barely rank in the top ten reasons to watch the film.

Not all of it was understood at the time, however, including the work of its stars (again, Lane garnered a Razzie nomination for her work, even though she’s credibly playing both a major pop star and a surly teen). While Paré’s performance in the film was, even before “Streets of Fire” was released, roundly derided — co-writer Larry Gross claimed that Paré’s work in the film was part of an “early fundamental disappointment” in the project, later writing that he was, there’s that word again, “disappointing” — watch the film enough times, and the stoic nature of his Tom Cody hits just right.

And if, after this admittedly full-throated and wildly effusive explanation of the profound charms of this previously derided classic hasn’t yet convinced you to check out Hill’s masterpiece, I offer a spoiler to sweeten the deal. That aforementioned “unexpected weapon”? There are two of them, a matching set that appears in the film’s final face-off between Tom and Raven. They are — and this is the absolute truth — a pair of pickaxes.

Everything else in “Streets of Fire” is big and bright and bold, but it all swirls around Tom, a calm center (save for his love of firepower and at least one instance of, understandably very bad in retrospect, hand-to-face violence in the guise of “saving” Ellen). We may be feeling what “Streets of Fire” is throwing down, but no one is taking it in more deeply than Tom Cody. (And that seems to hold true for Paré: while the actor never became a top-tier star, he’s been steadily working ever since, and even returned to play Tom Cody in an unofficial sequel in 2008.)

Only in fables. Only set to rock & roll. Only on these “Streets of Fire.”

Best of IndieWire

Sign up for Indiewire's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.