What’s In Store For IFFI, Mumbai & Other Indian Festivals Amid Political & Funding Challenges?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

While much of the global entertainment industry is witnessing a full-throttled return to in-person events, India’s festival circuit is experiencing a chequered re-emergence from Covid, in part due to political and funding challenges.

Three weeks ago, the country’s biggest government-run festival, the International Film Festival of India (IFFI) in Goa, held its largest and most star-studded physical edition ever, but was marred by controversy when Israeli filmmaker Nadav Lapid, head of the international competition jury, described competition title The Kashmir Files as “a propaganda, vulgar movie, inappropriate for an artistic competitive section of such a prestigious film festival”. His comments prompted a storm of both abuse and support on social media, while Israel’s ambassador to India, Naor Gilon, wrote an open letter condemning Lapid’s statements.

More from Deadline

Earlier this year, Mumbai Film Festival, held in the home of India’s Hindi-language (a.k.a. Bollywood) film industry, angered the filmmaking community by moving online even though cinemas were open and the country was not in the midst of a Covid wave. Usually held in October, the privately-funded festival had been planning a return as an in-person event scheduled for March 12-22.

Just a few months earlier, Priyanka Chopra Jonas had been announced as festival chairperson, injecting some serious star power into the event, and a strong line-up of premieres had been selected for the festival’s India Gold competition. But the festival was cancelled just a few weeks before it was scheduled to start, with the organizers citing “logistical and financial challenges”.

Of course, India is not alone in having problems staging film festivals amid a Covid context – many events disappeared during the pandemic, and even the biggest festivals have struggled with funding and related practical issues.

But India is one of the world’s biggest film-producing nations, so there’s a genuine need for a platform to launch local cinema, as well as introduce world cinema to a large and film-loving audience. Prior to the pandemic, festivals including IFFI, Mumbai and several smaller events appeared to be thriving. So why is India’s festival circuit taking so long to get back on its feet post-pandemic and are these issues likely to be resolved in 2023?

There is certainly hope that Mumbai Film Festival, which has not been held physically since October 2019, will make an in-person return in October next year. The exact reasons for the March cancellation remain murky, but when the filmmakers who had been expecting in-person premieres complained in an open letter, artistic director Smriti Kiran posted on Instagram: “Amongst many things, we have had an associate sponsor discontinue their partnership with us. While that has put accumulating pressure on us, we also understand the difficulties of our partners.”

While Kiran has since left the festival, Chopra Jonas and festival director Anupama Chopra are understood to be still attached, and the board of trustees of the festival’s organizing body, the Mumbai Academy of Moving Image (MAMI), is still active. It’s also understood that talks have been in progress with various parties to try to bring the festival back as an in-person event next year. However, the funding situation remains unclear and festival’s main sponsor, Reliance Jio, did not respond when contacted by Deadline for comment.

The MAMI board also declined to comment on the festival’s status when contacted by Deadline, but said that, while it’s too early to confirm anything, the festival is not gone for good. A notice on the festival’s website says: “MAMI is recalibrating. We will be back with more information in 2023”.

Meanwhile, some of IFFI’s choices this year have raised questions about the extent to which the festival is influenced by the central government and its Hindu nationalist agenda. The Kashmir Files was an odd choice for competition – not only because the film has stirred up anti-Muslim sentiment in India, and been banned in Singapore, due to its “potential to cause enmity between different communities” – but because it’s technically an old film, released theatrically in India in March and already widely available on streaming platforms.

While the film’s inclusion in competition does not appear to contravene the rules of a FIAPF [International Federation of Film Producers Associations]-accredited festival, it was openly supported at the time of its release by Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

Until this year, IFFI was co-organized by the Directorate of Film Festivals (DFF), which sits under India’s Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, and the Goa state government’s Entertainment Society of Goa (ESG). Founded in 1952, the festival is India’s oldest and has a storied history, in its early days welcoming guests such as Akira Kurosawa and Frank Capra. Held at the same time as IFFI since 2007, in an adjacent venue in Goa’s capital Panjim, co-production market Film Bazaar is organized by India’s National Film Development Corporation (NFDC), which also sits under the I&B Ministry, but as a Public Sector Undertaking (PSU) is expected to turn a profit.

Earlier this year, the DFF and three other government film-related organizations, including the National Film Archives of India (NFAI), were folded into the NFDC, in a move that was opposed by many in the Indian film industry as it places financial obligations on public sector activities such as film restoration.

This was the first year that IFFI was organized jointly by the NFDC and ESG, and there were several improvements – including a series of masterclasses and ‘In Conversation’ events, featuring major Indian and international talent, such as Kung Fu Panda director Mark Osborne and Fauda creators Lior Raz and Avi Issacharoff; as well as gala red carpet screenings that gave it the buzz of a world-class festival. IFFI can also rightly claim to be the country’s biggest pan-Indian event, as its screens contemporary and classic cinema in many languages from across the country.

But the presence of the government could be felt at the event – from the inclusion in the masterclass program of industry figures who have been vocal in their support of the Modi-led BJP government, such as The Kashmir Files star Anupam Kher, to the appearance of government representatives on many of the Film Bazaar panels. The opening and closing ceremonies featured lengthy speeches from government ministers.

The NFDC has responded to Lapid’s remarks at the closing ceremony by describing them as “unfortunate and unwarranted”, also stating that they were “absolutely Mr Lapid’s personal opinion” and “we strongly denounce the statement as well as its politicization and misuse of the festival’s platform towards that end.”

One of the five jury members, Indian director Sudipto Sen, has also distanced himself from Lapid’s comments. But the other three members of the jury – US producer Jinko Gotoh, French editor Pascale Chavance and Spanish filmmaker and critic Javier Angulo – have since stated that Lapid did in fact speak on their behalf.

When asked about the independence of IFFI’s programming, NFDC Managing Director and IFFI Director Ravinder Bhakar stated: “All films of Competition including The Kashmir Files have entered through a due elaborate multi-level process as laid down in the festival regulations. The three Indian Films of the Competition were selected by both the Indian Panorama Jury of 13 members and Preview Committee of 20 members, having a sound background in the field of films, arts and culture.

“As proud as we are that the grand jury judged and awarded the six best films and individuals of this year, it is also reiterated that IFFI stands behind its fair selection of films representing diverse themes and complex viewpoints from all over the world.”

NFDC added that it is also holding the Mumbai International Film Festival for shorts and documentaries (not to be confused with the MAMI-run event) once every two years: “Every effort is made to give a global platform to documentarians and short filmmakers and we have introduced a robust B2B ecosystem which has seen active participation from international and domestic OTT platforms.”

Thankfully, while India’s political landscape may have become more divisive in recent years, festival organizers from across the country say that censorship does not have a major impact on their programming.

As a central government-run festival, IFFI has always had decent programming, across both Indian and world cinema, but is conservative in its selection of local films. Although it’s difficult to ascertain whether that caution is due to political pressure or self-censorship, it came as no surprise that this year’s edition didn’t screen recent award-winning Indian documentaries, such as Vinay Shukla’s While We Watched, Shaunak Sen’s All That Breathes and Payal Kapadia’s A Night Of Knowing Nothing, some of which are critical or either Indian society or government.

Elsewhere, programmers from other festivals explain that they submit their line-ups to the I&B Ministry to receive a censor exemption and most of the time are allowed to screen what they want. Speaking off the record, one experienced programmer said that self-censorship by the filmmakers themselves is potentially an issue: “They may not want to show their film at a big festival in India if it’s going to result in a backlash on social media or more trouble down the line.”

Regional diversity

While IFFI and Mumbai are India’s best known film festivals internationally, the country has many other festivals, either funded by individual state governments or privately financed. Some of the most established include the International Film Festival of Kerala (IFFK), held in the south Indian state of Kerala; Dharamshala International Film Festival (DIFF), held up in the mountains of Himachal Pradesh in north India; and Kolkata International Film Festival, held in the capital of West Bengal. Each of these festivals is very different in character, but taps into a cinephile local audience and also attracts filmmakers and audiences from across India.

IFFK, which recently wrapped its 27th edition (December 9-16), managed to hold scaled down but in-person editions during the pandemic and the 2019 floods that hit Kerala, and this year has returned to its usual size, screening 184 films from 70 countries. Organized by the Kerala State Chalachitra Academy on behalf of the Kerala government, the festival has a well-regarded international competition – this year’s line-up includes Cairo film festival winner Alam, Berlin entry Memoryland and Jallikattu director Lijo Jose Pellissery’s new work Like An Afternoon Dream – along with sidebars such as India Cinema Now and Malayalam Cinema Today, for films made in the language of Kerala.

IFFK artistic director Deepika Suseelan explains that the remit of the festival is to bring the best of world cinema to India: “Since IFFK happens at the end of the year, taking place after all the major festivals, we have the privilege of showcasing the best films from throughout the year.”

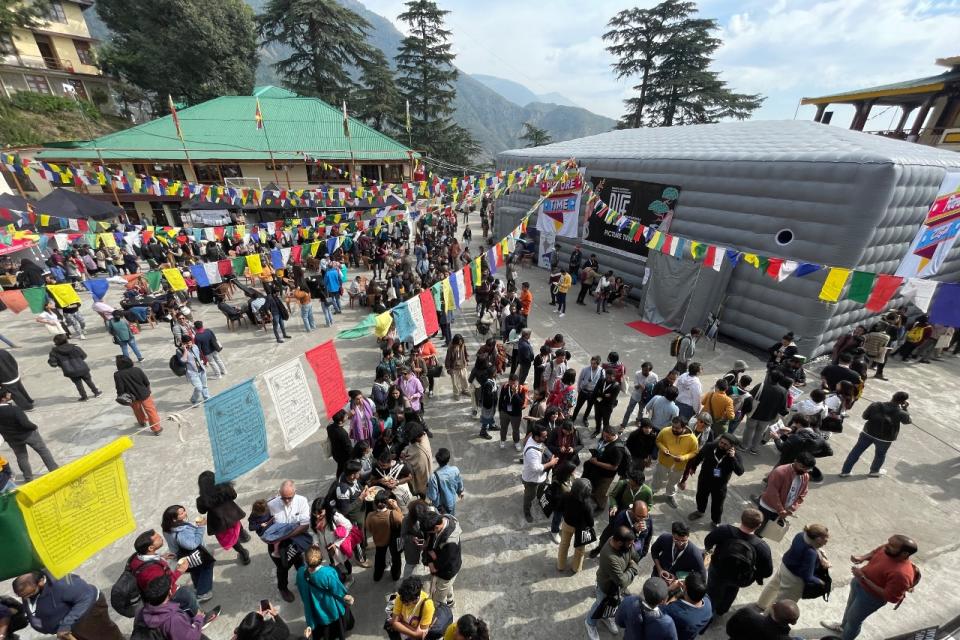

Meanwhile, DIFF, held in the town of Dharamshala, best known as the home of the Dalai Lama, describes itself as “fiercely independent in nature” and is funded through the support of sponsors, cultural institutions and the sale of festival passes (Indian film festivals sell passes rather than individual tickets). The non-competitive festival, founded by filmmakers Ritu Sarin and Tenzing Sonam, screens international features, documentaries and shorts, including South Asian films.

Sarin explains that this year’s edition (November 3-6) screened more South Asian films than usual, because so many films had been left without a physical premiere in India due to the pandemic and late cancellation of the Mumbai film festival. The festival’s India premieres included Fire In The Mountains and Writing With Fire, which both premiered at Sundance in 2021; All That Breathes, which premiered at this year’s Sundance; and Cannes Un Certain Regard title Joyland, Pakistan’s submission for the Oscar’s Best International Feature category, which recently faced difficulty being released in its home country.

While explaining that she doesn’t usually go for the “big Cannes titles”, Sarin describes DIFF as a small festival that promotes independent cinema: “We want it to be an intimate festival where filmmakers actually get to speak to each other, and also to audiences.” DIFF also runs a mentorship program for Himalayan filmmakers and this year partnered with France’s Produire Au Sud program on a lab.

IFFK and DIFF both say that, if Mumbai film festival doesn’t return, they would step up to premiere more Indian films. But both are cinephile-led events with niche positioning and funding limitations, so don’t have ambitions to become India’s leading international film festival (flying under the radar may be a wise approach in politically turbulent times).

It’s also likely that as the landscape of India’s multiple film industries is changing, the festival landscape will also shift. Even the West has woken up to the fact that Indian cinema is not just “Bollywood and the rest”, but has several different filmmaking centers. It may be more representative of Indian cinema to place equal emphasis on several film-related events serving different audiences and geographical locations, some government-led, some privately-funded.

The international film industry could then consider multiple festivals as opportunities to introduce their films to Indian audiences, or to find Indian films to program and distribute internationally, rather than focusing on a single event or filmmaking center. After all, other big markets like North America and China are less linguistically diverse, but both are home to more than one internationally recognized festival.

Best of Deadline

2022-23 Awards Season Calendar - Dates For The Oscars, Golden Globes, Guilds & More

Red Sea International Film Festival 2022: Best Of The Red Carpet Gallery

Sign up for Deadline's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.