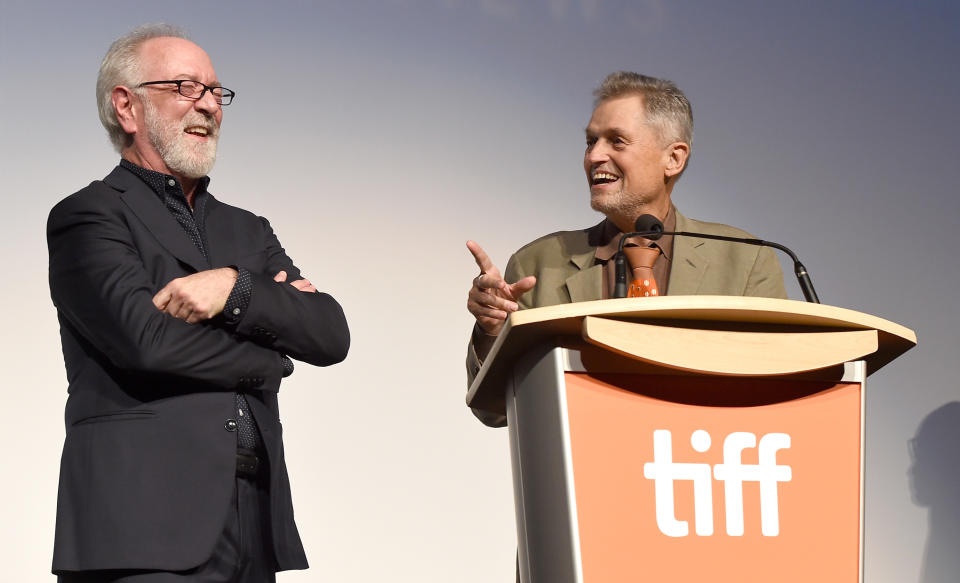

‘Stop Making Sense’ Producer Gary Goetzman Talks the Making of Rock Doc That Changed Concert Movies Forever

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

“The Silence of the Lambs” executive producer Gary Goetzman has been a major player in Hollywood for the last four decades (especially after he followed that Best Picture-winner by co-founding Playtone with Tom Hanks in 1998), but many in and around the film industry were unfamiliar with his story until Paul Thomas Anderson made a movie about it. “That was some version of my story, at least,” Goetzman chuckled when I asked him about “Licorice Pizza” during a recent Zoom interview from his office in Los Angeles, where he’s putting the finishing touches on “Masters of the Air,” a high-altitude Apple miniseries in the tradition of “Band of Brothers” and “The Pacific.” “So many events in ‘Licorice Pizza,’ are true, but everything around it is kind of not.”

Specifics notwithstanding, Anderson’s coming-of-age comedy — set in the San Fernando Valley circa 1973 and starring Cooper Hoffman as 15-year-old “Gary Valentine” — certainly nails a few key details about Goetzman’s eccentric, almost Gump-ian past, as well as his winsome grab life by the horns persona. Like his “Licorice Pizza” avatar, Goetzman really did start his career as a child actor, playing a small role in “Divorce American Style” before getting cast as one of Lucille Ball and Henry Fonda’s 18 kids in “Yours, Mine and Ours.” And like Gary, the ever-enterprising Goetzman really did launch an impromptu waterbed business whose clients included Barbra Streisand’s “volatile” then-boyfriend, “A Star Is Born” producer Jon Peters.

More from IndieWire

But for all of the many-splendored glimpses it offers into Goetzman’s teenage years, “Licorice Pizza” glosses over one of the most fortuitous chance encounters of his young life, and it ends before that encounter began to change the entire course of his existence. In the film, Gary’s 1968 appearance on “The Ed Sullivan Show” is highlighted by the fact that he gets to bring a Haim sister along as his chaperone. In reality, Goetzman’s fateful trip to New York was memorable because of someone he met once he got there: A promising 24-year-old by the name of Jonathan Demme.

Already a producer at heart, Goetzman knew how to recognize talent when he saw it. “I was as precocious as I am in [‘Licorice Pizza’],” he said, “and I was friends with all these guys who were probably eight-to-ten years older than me.” Goetzman had his own ambitions to be a director at the time, but he had so much fun helping out young directors like George Armitage (who would later make “Miami Blues”) and Joe Viola (1971’s “Angels Hard as They Come”) that he never got around to getting behind the camera himself. “At a certain point I decided ‘well, shit, how is this going to work out? Oh, I’m going to produce all their movies.”

Endowed with an awe-inspiring gift for follow-through, Goetzman did exactly that. “I was production manager on Jonathan’s first movie, ‘Caged Heat,’” he said, “and then after that we just kept thinking of stupid ideas together. My person had been chosen for me.”

Goetzman and Demme wouldn’t establish a consistent professional relationship until Hannibal Lecter sealed that bond in the early ’90s, but a mutual love of music sustained their friendship during the years when their careers were moving along separate tracks (Goetzman spent much of the ’80s working in the record industry while making cameo appearances in Demme classics like “Married to the Mob” and “Something Wild”). If those separate tracks never felt so far apart, perhaps that’s because Goetzman and Demme’s first major collaboration had profoundly rewired the relationship between music and movies, rendering them as inextricable from one another in the collective unconscious as they had always been in Demme’s head.

Goetzman and Demme have always been extremely clear about how complete the Talking Heads’ stage show already was before the two of them had the idea to shoot it (Demme once described it as “a movie waiting to be filmed”), but it wouldn’t be inaccurate to say that the origins of “Stop Making Sense” trace back to a phone call Goetzman received on one of those listless 1982 afternoons when he and Demme would sit around the pool and wait for opportunity to strike — which is what they did whenever they weren’t scouring record shops for new albums. “My brother was booking acts for CSUN [California State University, Northridge) at the time,” Goetzman recalled. “His job was to book The Motels and Oingo Boingo. And then he called and said ‘Dude, I think I’m going to book the ’Heads.’ And I just said ‘Jonathan, Grego’s going to try to get the ’Heads at CSUN,’ and Jonathan goes: ‘We’re filming it, man. 16 millimeter.’”

The Talking Heads ultimately passed on the irresistible opportunity to play a cheap show for a bunch of college kids, but it wasn’t much later that Goetzman received an offer of his own. “A girlfriend of mine named Nadia called and said ‘Gary, come to the show with me, my friend Bonny’s boyfriend is playing at the Greek Theater.’ And I was like, ‘Well who’s her boyfriend?’ Long story short, we figured out it was David Byrne and we were there.”

Goetzman wound up being unable to make it to the show, but he had a pretty decent back-up plan. “I was working nights at the time on an album — that’s the record business part of my story — and so I wound up asking Jonathan to go instead,” he remembered. Needless to say, Demme, one of the most creatively irrepressible filmmakers that Hollywood has ever known, was able to make a good impression. “He went to the Greek,” Goetzman continued, “Nadia took him backstage, and I think by the next day David was hanging out around the pool with us.”

I asked Goetzman if he was still capable of being starstruck back then, and he grinned like a little kid who just got an autograph from their hero. “Dude, it blew my mind. That was the best. I don’t know if it was a place David wanted to be or not, but he was there and we ended up having some incredible times at the pad.” There’s something about meeting musicians that just hits different, even for people who’ve worked in showbiz all their lives. “Oh, come on,” Goetzman agreed. “They create things you can dance to. So yeah.”

Goetzman says that he and Demme simultaneously arrived at the idea of making a concert film during the Talking Heads’ then-current tour, the way that good friends can think the same thing so naturally that it never seems relevant to note who bothered to speak it first. Goetzman had never served as the lead producer on a film before, but he said that making this one just felt like “the right thing to do,” and it wasn’t long before he and Demme found themselves obsessively confronting the same questions that anyone might ask themselves before embarking on a project like this one. “How do we do this? How do we make it special? How do we give the band as much of what we feel we can bring to the party as they would want and need?”

The questions may have been obligatory, but the answers that Demme and Goetzman came up with were unprecedented. In part, that’s because of the people who Goetzman knew. So far as Hollywood was concerned, he was more of a music guy at that time, and so he went to the music industry for the money, ultimately asking Warner Bros. Records to front the $1.2 million budget, which would be spread across four nights of filming at Hollywood’s Pantages Theater. “It was unheard of for a record company to be backing a theatrical film, “Goetzman said. The Talking Heads’ manager Gary Kurfirst had a lot to do with that, but so did Goetzman’s relationship with label chairman and CEO Mo Ostin. “I had known Mo since I was 14,” Goetzman said, “which is weird, but I did. And I didn’t want to blow his money. I felt a lot of responsibility for it.”

At the same time, he never really thought of the film would be a particularly lucrative venture, but having a record label foot the bill instead of a movie studio allowed for a different set of expectations: A concert doc would help eventize the band and move some more of their records, even if it didn’t set the box office on fire. The promise that Goetzman made to his old friend at Warner wasn’t “Burning down the house” so much as “Cool babies/Strange but not a stranger.”

Another reason “Stop Making Sense” felt so different from previous films of its kind is that Goetzman took a similarly gloved approach to the ’Heads themselves — good producers know when to let their talent cook. “We felt so lucky just to be there,” Goetzman said. “It was like we were hanging with our Beatles, you know?” And a 30-year-old fan who’d never really made a movie before wasn’t going to tell his Paul McCartney how to play guitar.

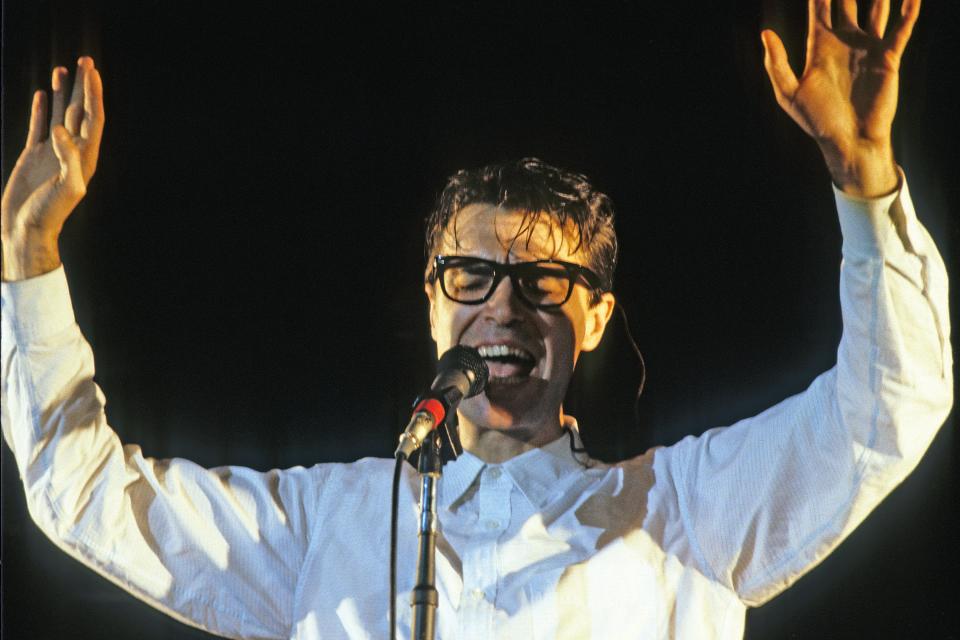

Asked if it was difficult to find the right level of creative input, Goetzman replied: “How about this: Anything the band wanted to do, we were happy to do. We weren’t giving them advice about this or that. I know Chris [Frantz, drummer] has a quote about something I said about not looking in the camera, but I don’t even recall saying that.” For the record, Frantz’s quote is that “The only directions we got from Gary Goetzman, who was technically the producer, were ‘Don’t look at the camera, and, for God’s sake, don’t pick your nose.” Considering that one of the film’s most famous shots finds Byrne strumming out “Psycho Killer” as he waddles directly at the lens in a low crouch, it’s fair to say that whatever advice Goetzman may or may not have given was disregarded all the same.

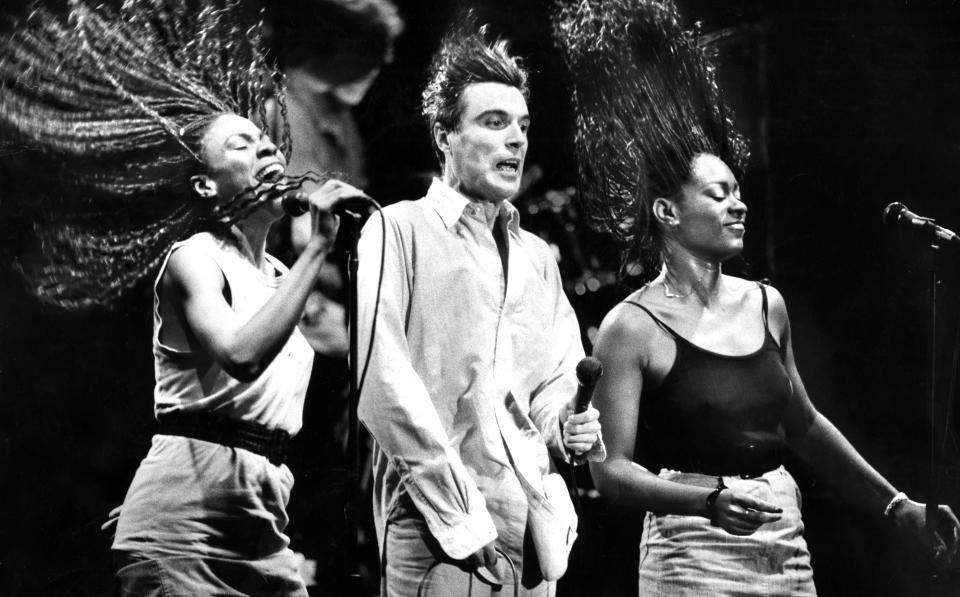

The challenge for Goetzman and Demme wasn’t about what the band was going to do, but rather how they were going to capture it. Demme’s solution was to push back against the wide-screen maximalism that had typified previous concert films in favor of something that felt more like a body-moving character study. In the obituary Byrne posted to his website just a few hours after Demme’s April 2017 death was made public, the Talking Heads frontman wrote that “Jonathan’s skill was to see the show almost as a theatrical ensemble piece, in which the characters and their quirks would be introduced to the audience, and you’d get to know the band as people, each with their distinct personalities. They became your friends, in a sense. I was too focused on the music, the staging and the lighting to see how important his focus on character was — it made [his] movies something different and special” (Byrne would later go on to express his appreciation for Demme and Goetzman’s inclusive approach, and cite the experience as a determinative factor in his decision to direct a feature of his own in 1986’s “True Stories”).

For Goetzman, who appreciated Demme’s approach in similar terms, it was all part of the director’s focus on “staying in the present,” which can be hard enough when you’re just in the crowd watching a show, let alone desperately trying to shoot the entire thing on film. “We only had six cameras,” the producer recalled. “We had great cameramen, and a fantastic DP in Jordan Cronenweth, but these were not concert shooters, they were movie cameramen. They were used to doing a shot and backing off and having a coke and a smoke and bullshitting with the crew and stuff and thinking about next shots. So we had to figure out a really good system to communicate with them.”

They also had to figure out a way to translate Byrne’s vision for the concert’s staging to an entirely different medium, which presented both a bold challenge and a rare opportunity to people shooting a show performed through geometric shapes, small gestures, and big suits; a show that did its best to split the difference between an intimate offering (“Hi, I’ve got a tape I wanna play”) and the kind of go-for-broke dance party that defies public embarrassment. Demme had a rough idea of where he wanted to be for certain parts of each song, but putting those plans into practice was easier said than done. “It was really difficult to light the show,” Goetzman said. “I remember on the first night we only had half of it lit and just kind of ran it through and everybody was racing around trying to find good camera angles during the songs.”

Some of the lighting difficulties the production encountered were self-imposed, as the decision was made to black out the crowd at the Pantages so that movie audiences would feel as if the show were being performed for them. Demme had considered including more crowd shots in the film, but filming them — while technically simpler — also required even more lighting, and had an inhibiting effect on concert-goers who might only give into the groove if they could forget that anyone else could see them… let alone might see them over and over again for all eternity. The band has described the one night that Demme lit the audience as “the worst Talking Heads performance in the history of the band’s career,” but Goetzman, inveterate producer that he is, saw the disaster for its silver lining. “They’re talking about the Tuesday night show where we didn’t really have the stage lit and we had other problems, but whatever they felt was so bad about it — which in my memory I don’t remember as being so bad — I think must have inspired the incredible performances they gave the next two nights.”

It also must have inspired Demme to narrow his focus even more, sometimes privileging close-ups of shoes and shadows over wide shots of the full band at fever pitch. “Stop Making Sense” offers plenty of spectacle in spite (and because) of that approach, but the film’s ultra-palpable sense of collective fun isn’t derived from a god’s-eye-view look at all of those people putting on a show together approach, but rather from how Demme patiently silos individual displays of I was born for this devotion so that he can delight in the magic of blending it together — in the infectious euphoria of two or three or eight people all having the best night of their lives at the same time. The result is a film so euphoric that, even 40 years later, it still feels like it’s happening for the first time right in front of your eyes because your body only responds to that kind of happiness in the present tense.

And that presentness, so much more acute in the context of a band that would later experience a publicly acrimonious breakup, is ironically what makes “Stop Making Sense” such an accurate crystallization of the energy behind its creation. I asked Goetzman if everybody behind the scenes was as high on the project as it seems onscreen, and he answered without hesitation: “Absolutely. We were all so intertwined with the big idea of getting this show on film in the best way we could. Whether that was the band or the film loaders or anyone else, we all were so passionate about making this the best it could be, and then the band just took it way beyond whatever we imagined. It’s so filmic. I think David probably has sprockets in his brain or something because he’s such a natural about it.”

Another regard in which “Stop Making Sense” represented a paradigm shift for concert movies is the technology that was used to create it. Shot on film and edited in Hal Ashby’s editing room (“which was fantastic because Hal Ashby would just come walking down the stairs,” Goetzman recalled), the movie was one of the first examples of its kind to record audio digitally, which made it that much easier to remaster for its upcoming 40th anniversary theatrical re-release. “When A24 called about it I was surprised that they wanted to do a full-blown re-release of the movie,” Goetzman said, “which is unheard of [for a concert film]. They wanted to up it to 4K. They said ‘Let’s do an IMAX mix,’ and then ‘Let’s do a Dolby Atmos mix.’ I was blown away, man.” When asked how the film looks on IMAX, Goetzman only smiled and said: “Let me tell you… the big suit? It’s REALLY big.”

It’s also a fittingly large-format séance for the spirit of an absent friend whose warmth continues to follow Goetzman like a ray of sunshine on his back; the same friend he met backstage at “The Ed Sullivan Show” when he was just a kid, and whose presence he can’t wait to feel again in theaters across the country. Goetzman and Demme made a lot of movies together over the years, and a lot of memories beyond that, but speaking to the producer left me with the distinct impression that “Stop Making Sense” was special in some regard — that of all their collaborations, this one was singularly expressive of the exuberant and creatively inexhaustible person Demme was. When I asked Goetzman about this, he offered an immediate response. “Yeah,” he said. “Jonathan got to dance while he was directing.”

“Stop Making Sense” will return to theaters as a TIFF World Premiere and Global IMAX Live event on September 11. A24 will release it exclusively in IMAX on Friday, September 22, and in theaters everywhere on Friday, September 29.

Best of IndieWire

Where to Watch This Week's New Movies, from 'Blue Beetle' to 'The Adults'

The 50 Best Sexy Movies of the 21st Century, from 'Spring Breakers' to 'X'

Sign up for Indiewire's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.