Stonewall generation has a warning for the LGBTQ community post-Roe: 'Be really afraid right now'

Alston Green, 71, has a blunt message for LGBTQ people, especially the young: “Be really afraid right now.”

Don Bell worries that “all the work that we have done for the 72 years I have been around is at risk.”

Lujira Cooper, 75, nails it in four words: “Fight like hell – vote.”

Green, Bell and Cooper are among LGBTQ elders whose alarm bells are blaring that the hard-fought gains notched by their Stonewall generation could be on the precipice of being gutted.

This year has been a troubling one for the LGBTQ community: 316 anti-LGBTQ bills have been introduced so far in 2022, according to the Equality Federation, from “don’t say gay” bills to health care access limits to youth sports bans.

A surge in anti-LGBTQ threats and violence unsettled normally joyous Pride celebrations.

BARRAGE OF LEGISLATION: Florida's 'Don't Say Gay' bill sparked national backlash. But more legislation is brewing.

Then in June came the thunderclap: the Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe v Wade – and a concurring opinion by Associate Justice Clarence Thomas calling on the court to “reconsider” other rights such as gay marriage.

“I hope younger people are listening … because it’s really important for them to know what’s next,” Green said. “There’s so much at stake.”

WHAT COULD BE NEXT: From LGBTQ rights to interracial marriage, abortion ruling could be map for GOP's next push

Who are LGBTQ elders?

There are nearly 3 million LGBTQ adults over age 50 in the U.S., according to a report by think tank the Movement Advancement Project and SAGE, an advocacy group for LGBTQ seniors. Of those, 1.1 million are 65 and older, the report says, and 1 in 5 are people of color. One-third of LGBTQ seniors live at or below 200% of the federal poverty level, according to the report.

LGBTQ elders – sometimes called the first "out generation" – confront challenges facing other seniors, but made more arduous by a lifetime of grappling with bias, isolation and housing and health care issues, said Michael Adams, CEO of SAGE.

Much progress has been made over the years, Adams said, but in the current climate LGBTQ seniors have cause for concern. More older people could be denied admission into elder care facilities, and others would feel the need to "hide who they are, to hide their pictures, to make believe they are heterosexual."

"We are living at a time where there is this big cultural, social and political backlash against the progress LGBTQ folks are making," he said. "So that creates the specter that perhaps things could get even worse in elder care and elder services."

DISCRIMINATION ESCALATES: Most LGBTQ Americans face discrimination amid wave of anti-LGBTQ bills, study says

‘A time of possibility’ to a time of concern

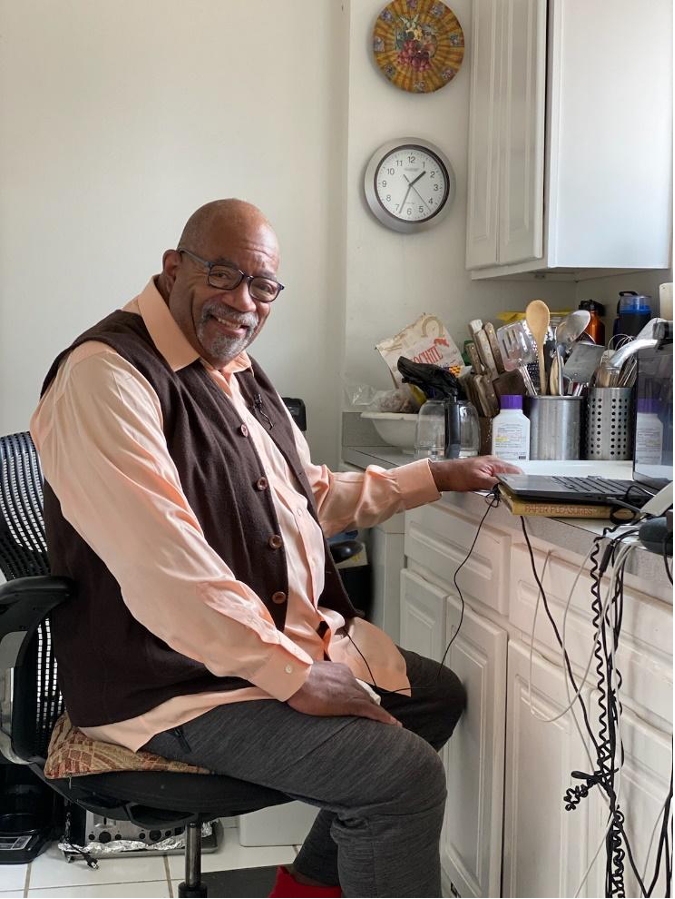

Green is a longtime activist with a vibrant career in the design industry. He came out in the summer of 1969 while attending the Parsons School of Design in New York, a city he recalls pulsing with energy and opportunity for self-expression.

“I was discovering myself. There was so much going on here it just made it a little easier to approach that conversation about myself,” he said. “I thought it was a time of possibility.”

Green preferred ballrooms to the bar scene, which he says was not always welcoming to people of color. But the uprising at the Stonewall Inn, which ignited the gay rights movement, was monumental.

“People had just had enough of what was being shoved at them,” he said.

'WE CELEBRATE EACH OTHER': LGBTQ, female woodworkers aim to carve out more space in a field built for men

Decades later, the LGBTQ community and the Black community are still in the crosshairs, Green said, whether it’s threats to gay rights or police shootings of people of color. He sees most Americans as “too comfortable. This is why these things keep happening to us … because we think 'oh they are not going to do that.' And then when they do it, all of a sudden it’s a shock.”

But Green is resolute that LGBTQ people will fight: “For 50 years, I was out protesting, marching and making sure things change, and I’m not going to see it roll back.”

'YOU ARE SEEN': A record 7.1% of US adults now identify as LGBTQ, new poll shows

‘If they can take away my rights, they can take away yours’

Cooper lived as an openly gay Black woman during the summer of Stonewall, working at New York’s 34th Street YMCA, a “haven” of safety for LGTBQ people. She recalls feeling the sting of bias because of the color of her skin, rather than her sexuality.

Cooper, who overcame poverty and homelessness to become a successful writer, is not surprised by negative shifts on rights in recent times.

“Authors have been telling us this possibility for years,” said Cooper, citing the 1935 political novel "It Can’t Happen Here" about the rise of a U.S. dictator. “It’s no longer it can’t happen here, it’s more like it might happen here.”

WHY THE EQUALITY ACT IS IMPORTANT: LGBTQ Americans hope push for Equality Act will finally end bias

Cooper fears for LGBTQ seniors who won't get the assistance they might need if they are afraid to reach out.

“There are a lot of people out there who are getting older, and their health is getting bad. So they may have go to into nursing homes or assisted living or get help in their homes – and they are not going to want to identify with a group that’s being targeted,” she said.

Cooper said it’s crucial to elect people who will restore freedoms, and she hopes young people rally to that cause. “Older LGBTQ people need to inform their grandchildren, their nieces, their nephews: Hey, if they can take away my rights, they can take away yours.”

RECLAIMING A FORMER SLUR FROM ITS HISTORY OF HATE: Is it OK to use the word queer?

‘My life’s work product is on the line’

Bell, who spent his career in higher education administration, can trace the roots of his activism to the shocking death of Emmitt Till when Bell was just 5.

“It was the first time I saw adults cry in public,” he said. “And for the first time I realized there is danger in the fact that I was a boy born with Black skin.”

The native Chicagoan was engaged to his high school sweetheart – until he fell for a resident adviser in college. Bell recalls asking God: “Isn’t being Black enough? Do I have to be gay, too?”

But he soon learned another valuable lesson that has been his backbone through life, and with that came self-acceptance: “You use the experience of one repression to inform the other.”

Bell, who raised two sons as a single parent, confronted a more daunting challenge in recent years after being a longtime caretaker for his parents, a challenge many older LGBTQ seniors face: housing. He had just lost his beloved mother when he realized: “I had to live my own life as an aging Black gay man. What was that going to look like? My first concern was where was I going to live.”

HISTORY BEHIND PRIDE: How the LGBTQ celebration came to be

LGBTQ seniors have always been vulnerable, and housing issues can be at the top of the list, he said. Bell, who was concerned about opportunities for socialization, safe spaces and acceptance, was fortunate to have won a lottery for Chicago’s first LGBTQ-inclusive senior residence.

But now with a disturbing landscape for the community, concerns are ratcheting up for other seniors who may fear being “re-closeted” or may become even more isolated, he said. That is why it’s crucial for young LGBTQ people to step up, Bell said.

“I hope that they are outraged at the loss of what is normal to them even though it wasn’t normal to us. I hope that they will be motivated to make connections with their elders while they are here,” Bell said. “My life’s work product is on the line.”

Adams said LGBTQ elders are determined to quell the backlash.

"As bad as things are right now with 300 plus hateful bills, our elders remind us we have been here before," he said. "We will push back, and we will re-establish the progress we need to make."

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Post-Roe America: Stonewall generation fears anti-LGBTQ backlash