Stephen King in Five Films

This feature originally ran in 2015. We’re reposting it as Castle Rock gets set to premiere.

Ever felt overwhelmed by a director’s extensive IMDB page? In Five Films is here to help, offering a crash course and entry point into even the most daunting filmographies. This is your first step toward fandom. Take it.

Anyone familiar with our “In 10 Songs” feature knows that we don’t necessarily pick the 10 best tunes by a musician, but the ones that best represent their career, warts and all. The same goes for “In Five Films.” And, to put it bluntly, Stephen King has a lot of warts.

Remember, we’re talking about cinematic takes on his novels and short stories, a puzzling body of work if ever there was one. Has there been another author who has so many good books (I’d wager he’s knocked it out of the park about 80 percent of the time) with so many shitty film adaptations? Even more puzzling is that there doesn’t seem to be a consistent formula for success or failure.

King movies have both soared and tanked under his heavy involvement (e.g. Pet Sematary and Maximum Overdrive, respectively), been both loved and ridiculed for departing drastically from the source material (e.g. The Shining and Graveyard Shift, respectively), and everything in between.

Our five categories may not represent every aspect of King’s numerous journeys from page to screen, but they’re certainly a start. We promise you this, constant reader (or constant viewer): If you’ve never seen a Stephen King film (wait, you’ve never seen a Stephen King film?), these five will give you a full range of their differing qualities, warts and all.

–Dan Caffrey

Senior Staff Writer

__________________________________________________________

The Miniseries

The Stand (1994)

King was no stranger to the network TV miniseries. Throughout the ’90s, adaptations of ambitious novels like It, The Tommyknockers, and The Langoliers would unfold in two-hour blocks across several nights. Unfortunately, the trade-off for those extra minutes was minuscule budgets, directorial ineptitude, and the content restrictions that accompany network TV. This was hard R content being adapted into prime time “gather ‘round the boob tube” television. Needless to say, they were all pretty awful.

But it’s Mick Garris’ 1994 take on The Stand that’s somehow both the best and worst of these adaptations, if only because it shoots for the M-O-O-N and falls so spectacularly short. There’s plenty to like in it, including some gruesome set pieces, a confident tone, and fine performances from Gary Sinise, Matt Frewer, and Ossie Davis (let us never speak of Corin Nemec’s turn as Harold Lauder, however). But six hours isn’t enough to tell this story. Hell, 12 hours probably wouldn’t be enough. The Stand was the closest any King miniseries got to getting it right, but it was still so, so far away.

If there’s one thing to be taken from King’s ’90s and early-’00s miniseries adaptations, it’s that his epic novels are probably best left to the page. His best movies are his smallest ones, though we might never have figured it out were it not for this era of experimentation. But hey, we’re in the midst of a King miniseries resurgence, what with Hulu’s recent take on 11/22/63 and Audience’s Mr. Mercedes. If nothing else, at least they’ll at least be able to say “fuck.”

–Randall Colburn

__________________________________________________________

The Excess

Maximum Overdrive (1986)

Wanna know what happens when King gets behind the big rig wheel? He blasts a lot of AC/DC, dabbles in some off-road fun, and turns up the gore to Maximum Overdrive. Loosely based on his short story “Trucks”, which originally appeared in his exceptional 1978 short story collection Night Shift, this 1986 science fiction action horror romp is the closest approximation of either genre’s boiling point, when “asinine” becomes “batshit crazy” and “batshit crazy” turns fundamentally intrusive.

Starring Emilio Estevez, Pat Hingle, Frankie Faison, and Yeardley Smith, this “moron movie,” as King has since called it, is basically a 97-minute video essay on what would happen if inanimate objects — namely cars and trucks that look like the Green Goblin — could come to life and seek revenge. For what? Didn’t we build them? Give them life? Yes, but they’re pissed and they want blood. They don’t eat people, they don’t swallow souls, but they want to kill. Spoiler: It’s aliens.

Maximum Overdrive is a cautionary tale in itself. Here’s what happens when a creator is given absolute control and zero restraint: We get a bunch of Little Leaguers struck to death by cans and/or flattened by construction equipment. We get violent ATM machines. We get a shameless, nearly two-hour-long commercial for Angus Young and co. It’s obscene how this ever came to fruition, but also something worth marveling at nearly 30 years later. It’s essential for its tomfoolery, yet also supremely King.

–Michael Roffman

__________________________________________________________

The Anthology

Creepshow (1982)

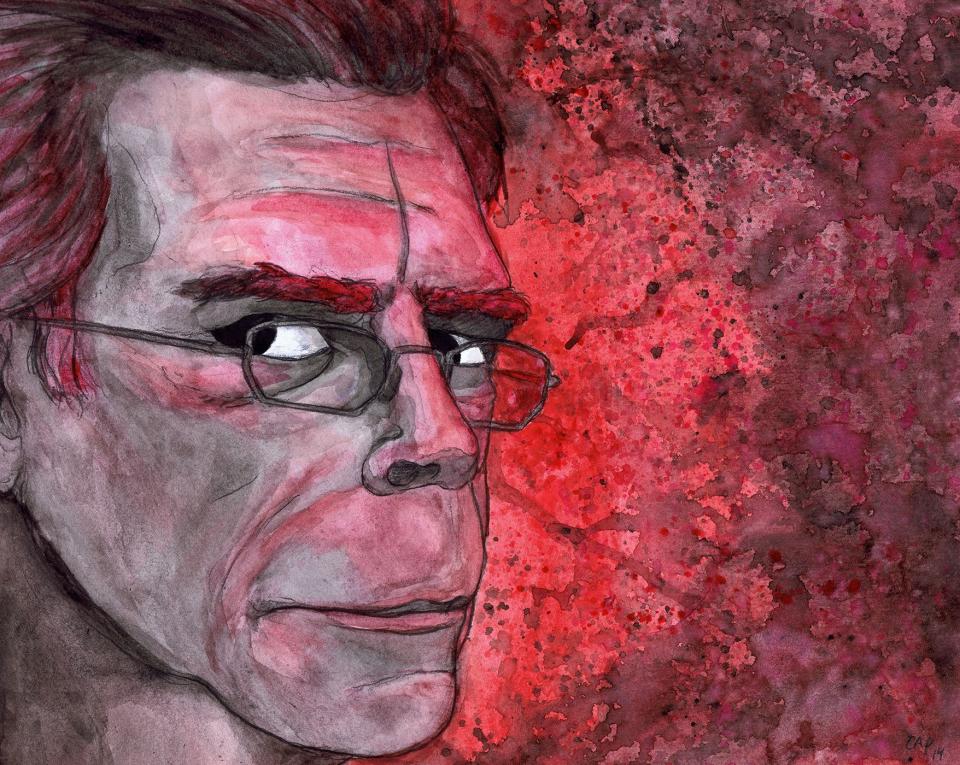

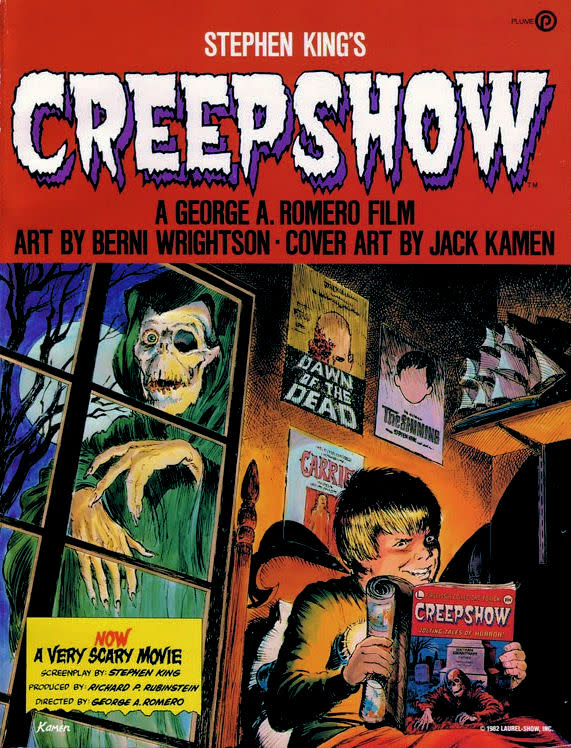

King once called himself “the literary equivalent of a Big Mac and fries,” so he’d probably scoff at the notion that he’s elevated the horror genre over the years. Self-deprecation, however, doesn’t change the fact that, intentionally or otherwise, he’s spurred his contemporaries to up their game with little things like character development, moral complexity, and social commentary.

Still, any horror fan first gets drawn to the genre by its more visceral elements — scary monsters, nasty humor, and lots of blood — and that’s what Creepshow is all about. And why wouldn’t it be? King and the late director George A. Romero conceived the film as an homage to the EC horror comics of their youth, so they naturally go whole-hog with the depravity across five tales and one wraparound story.

Each yarn pushes its macabre element to a place so maximal in its darkness that the whole thing becomes as hilarious as it is unnerving. You shouldn’t be laughing at a woman’s abusive, undead father baking her head into a cake or an old man’s body convulsing into an explosion of cockroaches, but when the creators are having so much fun, it’s hard not to join in. It also doesn’t hurt that Romero uses intentionally hacky comic panels for his transitions, as well as several animated interludes with our ghoulish, silent host, The Creep.

Another part of Creepshow’s success stems from its anthology format, proving that King’s early short stories work best when they’re just that: short stories. Their respective adaptations (two of the five tales come from one-offs published in men’s magazines) get in, get gory, and get out, a far cry from the pointless narrative expansion of duds like Children of the Corn, Maximum Overdrive, and Graveyard Shift. King would go on to serve up prime rib with potatoes au gratin many times in his career (see our upcoming entry on The Shawshank Redemption), but sometimes you just want to scarf down that Big Mac and fries.

–Dan Caffrey

__________________________________________________________

The Upgrade

The Shining (1980)

“I think stories of the supernatural are fundamentally optimistic, don’t you? If there are ghosts, then that means we survive death.” That’s the voice of Stanley Kubrick on the phone with King one early morning before shooting The Shining. A befuddled King, dripping with blood as he was caught off-guard shaving his face, went with it and proceeded to ask him about hell, to which the late director replied, “I don’t believe in hell.”

King often tells this story, which he calls his “only preproduction discussion” for what would wind up being his least favorite film adaptation, The Shining. It’s a telling exchange in that it subtly captures the wildly different mindsets of the writer and the late auteur, hinting at Kubrick’s changes from page to screen that would haunt King for years. So much so that he would wind up denouncing the film and attempt a remake of his own for the small screen in 1997.

“The book is hot, and the movie is cold; the book ends in fire, and the movie in ice,” King argued to Rolling Stone last year. “In the book, there’s an actual arc where you see this guy, Jack Torrance, trying to be good, and little by little he moves over to this place where he’s crazy. And as far as I was concerned, when I saw the movie, Jack was crazy from the first scene.”

The Shining is inarguably an excellent film. It’s just not King’s story. The basic components are there — troubled family trapped in a haunted hotel — but Kubrick’s hardly invested in the narrative, which is why the end result is a far more cerebral horrific experience. The filmmaker scribbled down the book’s themes of domestic abuse and alcoholism and imbibed them with a morose ambiguity. And since nothing is black and white, the stakes don’t just feel higher, they’re eerily undefined.

As Rodney Ascher’s Room 237 proves, there’s a lot that’s left to interpretation in Kubrick’s re-imagining. Yet there’s a dreadful, inherent evil implied by its surreal atmosphere. Right from the get-go, the film reels you in with wide shots, claustrophobic sets, and droning scores, slowly closing the door behind with each passing step. It’s a feeling that arguably trumps the novel’s more familiar beats and a move that ably nixes a sentimental ending. Bye bye, Ghost Dad!

Other future directors would share their own unique visions while reading King’s work — Frank Darabont and Rob Reiner come to mind — but none of them have ever come close to the grand departure of Kubrick’s reworking. It’s a fine example of what happens when two great minds collide and only one prevails. In this case, the winner is Kubrick, who managed to carve out such an iconic piece of filmmaking that King had to write a cautionary preface in his sequel, Doctor Sleep, years and years later.

White man’s burden, Stephen, my man. White man’s burden.

–Michael Roffman

__________________________________________________________

The Prestige

The Shawshank Redemption (1994)

King fans love telling snobs that The Shockmeister was responsible for the likes of Stand by Me, The Green Mile, and, of course, The Shawshank Redemption. Such revelations used to inspire looks of stunned disbelief on the faces of unbelievers, cracking open the door just enough to possibly convert another King fanatic. That happens less these days, as King’s output on the page and screen has skewed away from straight horror for a while now. Our little baby’s all grown up!

But it was The Shawshank Redemption, adapted from King’s novella Rita Hayworth and Shawshank Redemption, that truly propelled King from his B-movie roots to the A-list’s pristine red carpets. Oddly enough, the whole thing sorta came out of nowhere. It was the pet project of nascent writer/director Frank Darabont, who impressed King with one of his short films before buying the rights to Shawshank for $1 (a deal King often offers to upcoming filmmakers). Allegedly, Rob Reiner apparently offered Darabont $2.5 million for the rights, but Darabont believed in his own vision enough to hold on to ‘em. And, in one of Hollywood’s rare cases of art transcending capitalism, Shawshank nabbed seven Academy Award nominations despite tanking at the box office.

Credit Darabont’s muscular script and confident pacing, which trades the subtlety of King’s novella for bravado. Take the assassination of inmate Tommy Williams. In the novella, he simply disappears, but the film builds suspense and pathos from the untimely fate he meets at the hands of Bob Gunton’s Warden Norton and Clancy Brown’s Captain Hadley. It’s on the nose, sure, but makes for some gripping entertainment.

But it’s not just Darabont’s writing and directing talents that made Shawshank an Academy favorite, it was the filmmaker’s emotional connection to the humanity at the heart of King’s writing, a trademark of the author’s work that’s often eclipsed by the sensational subject matter. Even King at his most gimmicky — Christine, Needful Things, Under the Dome — benefits from a deep well of empathy and relatable behavior. Darabont’s fine cast emphasizes relationships above all, allowing the film’s escape plot to heighten the story rather than anchor it. There’s a reason the film is remembered more for quotes like this than it is for the actual story.

There’s Oscar gold in the shores of King’s stories. It’s just that most directors don’t have the tools to dig it up. Bully for you, Darabont.

–Randall Colburn