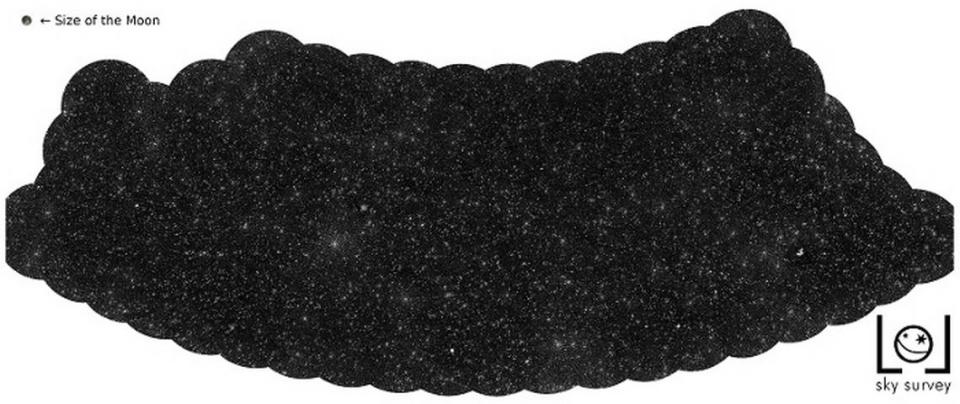

Stars? Nope, those are 25,000 supermassive black holes — and they took years to find

What appears to be a screen shot of countless tiny, twinkling stars in outer space is actually a map of 25,000 supermassive black holes, each located in its own faraway galaxy.

The project required the combination of 256 hours of sky observations over several years, yielding the most detailed map of these kinds of black holes, “which are millions, if not billions, of times as massive as the Sun,” according to NASA.

The international team of astronomers says their map will help provide “unique insights on physical models for galaxies, active nuclei, galaxy clusters and other research fields.”

The study has not been peer reviewed, but will be published in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics. The preprint was published Feb. 12.

The astronomers used 52 stations spread across nine European countries equipped with Low Frequency Array (LOFAR) antennas — the largest radio telescope operating at the lowest frequencies that can be observed from Earth — to detect radio emissions emitted from matter that catapulted outwards at the speed of light while drifting too close to the supermassive black holes.

These radio emissions are complicated by the ionosphere, the boundary separating Earth’s lower atmosphere where we live and the vacuum of space. This layer is full of free electrons that are constantly buzzing around, adding a cloudy lens to any telescopes trying to snap clear photos of the solar system.

“It’s similar to when you try to see the world while immersed in a swimming pool,” study co-author Reinout van Weeren, a Clay Fellow at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, said in a news release. “When you look up, the waves on the water of the pool deflect the light rays and distort the view.”

So, the team had to invent a new method of converting these radio signals into images of the sky. They did this by applying new algorithms to supercomputers that corrected the blurry effect from the ionosphere every four seconds.

“After many years of software development, it is so wonderful to see that this has now really worked out,” Huub Röttgering, scientific director of the Leiden Observatory in the Netherlands and last author of the study, said in the release.

The map currently covers 4% of the northern half of the sky. The researchers said they plan to continue their work until they’ve mapped all supermassive black holes of the entire northern sky.