How ‘Spirited Away’s’ Oscar Win Exposed the Academy

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The early years of the Academy Award for Best Animated Feature promised a future that never came to pass. Its current state as a depressingly predictable category dominated by whatever Disney released that year is one that feels limited through intention rather than ignorance, and it was 2003’s awarding of Spirited Away that sparked a sequence of events that spawned the show we know today.

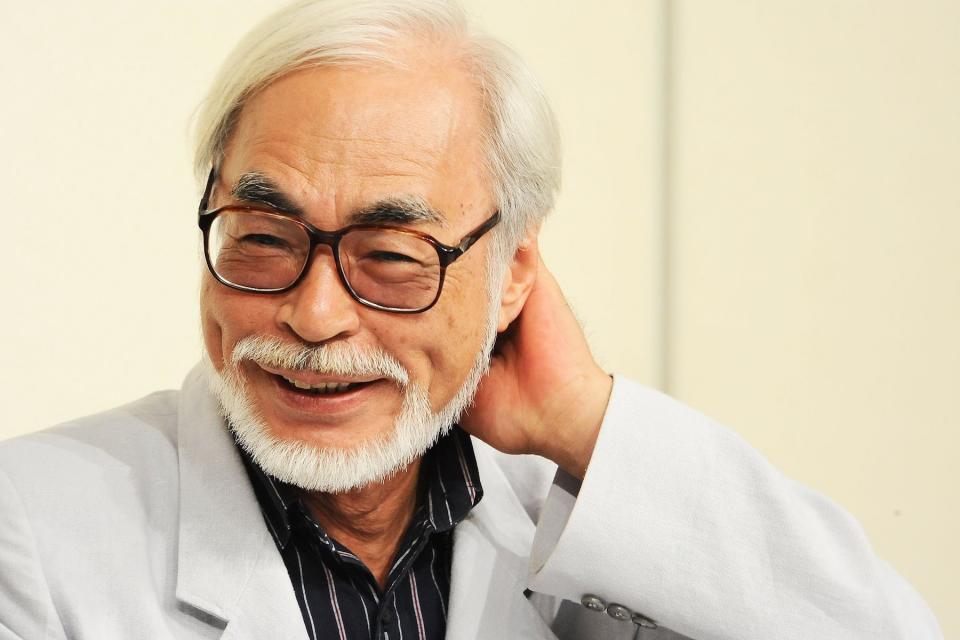

Five different studios took home the first six awards. With CG, traditional and stop-motion animation all represented, it seemed like the diversity of animated cinema would be a focus of the category. In 2003, Hayao Miyazaki’s Spirited Away won the second-ever Best Animated Feature, an intoxicating dreamlike adventure which compelled global audiences. Showcasing Japanese animation so early on felt like a statement from the Academy. The worldwide animation industry had seen rich and groundbreaking stories for years before the awards category was introduced in 2002, so it was only right for the Academy to honor that in their celebration of cinema.

More from Rolling Stone

Oscars 2023 Live Stream: How to Watch the 95th Academy Awards Online

Jimmy Kimmel Wants Nothing More Than to Interview Trump in Prison

In the 20 years since Spirited Away’s win, it stands as the only animated feature award won by an animation house not based in North America or Europe.

The Academy has struggled to recognize non-Western cinema at all in that time. The first Best Picture win for a foreign language film outside of Europe didn’t come until 2020 for Bong Joon Ho’s South Korean thriller Parasite, despite appreciation for foreign cinema from the industry at large.

Academy America-centrism does not even reflect the attitudes of many of the world’s finest filmmakers. Directors like Martin Scorsese show a deep appreciation for worldwide film, having set up The World Cinema project and The African Film Heritage Project, both with the aim of preserving films from underrepresented regions. Though they’ve celebrated Scorsese’s work, the Academy has been slow to adopt his ideals.

Ironically, it was the act of awarding an Eastern film with the Best Animated Feature Oscar that scarred the Academy into never repeating the feat. Highly decorated animated films have come from non-Western regions yearly, like Satoshi Kon’s Paprika and Isao Takahata’s The Tale of the Princess Kaguya building on the legacy of Spirited Away. Their lack of recognition from the Academy comes from a fear of self-reflection, something forced on them by Miayazaki upon his winning of the award. His refusal to attend the show, citing America’s invasion of Iraq as the reason, put the Academy at the center of a political debate. The Oscars want to be seen as a celebration of all cinema. Miyazaki exposed their place as a cog in the machine of American imperialism.

Spirited Away is a breathtakingly beautiful film. Miyazaki’s vision of a society of spirits ushers you through a blissful adventure while commenting on our all-consuming capitalist system. Being the first Studio Ghibli film distributed in the West by Disney, it caught on like wildfire, leading to its much-deserved Oscar triumph.

However, when it came time to accept the award, the Japanese auteur was missing. After the cameras scanned the crowd for his face to no avail, presenter Cameron Diaz accepted it on his behalf. Soon after, stories materialized about how Miyazaki was hard at work on a new film and was therefore unable to attend, but the director contradicted this cover-up in a 2009 interview.

“The reason I wasn’t here for the Academy Award was because I didn’t want to visit a country that was bombing Iraq,” he told the LA Times. “At the time, my producer shut me up and did not allow me to say that, but I don’t see him around today.” (He later accepted an honorary Oscar in 2014.)

The American invasion of Iraq having a “profound” impact on Miyazaki is no surprise. Like most Japanese people born in the 1940s, his childhood was marred by the American atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. To jump forward 60 years and see that same country raining terror on another Eastern land caused unknowable distress in a man who yearns for the progression of mankind. Miyazaki’s sensitivity to international conflict is well-documented.

In quotes from Tokiko Kato’s book One in a While Talk of the Old Days, he solemnly said “We felt that the world was going to get better. So when the Yugoslavian ethnic wars happened we were dumbfounded. What was going on? Were we just going backward?”, displaying his desperation for a hopeful future.

Humanity’s propensity for war and violence has always found itself at odds with Miyazaki’s work. Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984) depicts an Earth slowly rotting due to apocalyptic war, while 1997’s Princess Mononoke details how war is a byproduct of human hubris. His follow-up to Spirited Away would carry his strongest anti-war sentiment. Howl’s Moving Castle was born from Miyazaki’s rage at American imperialist policies, depicting gut-wrenching scenes of destruction.

Masked as a celebration of global cinema, the Academy holds inseverable ties to America. For Miyazaki, attending the Oscars was not simply showing up for an award show but an endorsement of the nation and its policies. Miyazaki seemed disappointed that his film had been marked as a touchstone in American culture, later claiming, “Around the time of the Iraq War, I even made a slightly conscious effort to create a film that wouldn’t be very successful in the United States.” Being perceived as a powerhouse of entertainment, a land of dreams and good, old-fashioned capitalism, America rarely has to contend with its perception from the outside world — particularly those who disapprove of their imperialism.

The Academy is not an institution of film culture but of American film culture. The distinction is vital. The power to control what art is seen as good or bad is fundamental for propaganda. This is recently exemplified in the slew of nominations for American Sniper in 2015, a film celebrating the deadliest marksman in U.S. military history.

Miyazaki’s quotes put a mirror in front of the Academy, a scenario they have worked hard to avoid. The dominance of straight white men is well-publicized when it comes to the awards, a circumstance not unwittingly conjured but a feature which protects the Academy from criticism. Developing a club of people with similar backgrounds who love — or make — similar movies builds an almost impenetrable echochamber.

Inviting Miyazaki, a man with no obligation to respect American culture, to your awards show displays a risk that the Academy has been hesitant to repeat. The thriving world of non-Western animation has been shunned in favor of repeated wins for Disney and Pixar, who have collected 13 of the last 16 Oscars for Best Animated Feature.

This track record reeks of fear. The Academy knows that their reputation hinges on the belief that American cinema is the most worthy of celebration and that their decisions reflect a correctness about art. Without being billed as the most important night in the cinematic calendar, ABC loses viewership, the Academy loses credibility, and America loses an asset.

Parasite’s Best Picture win was used to frame the Academy as an increasingly progressive institution. After receiving backlash in the form of the #OscarsSoWhite, they appeared to be making steps toward representing the global film community.

Unfortunately, the Best Animated Feature category has yet to see such progress. It took until 2018 for another non-white director to be recognized in the category, and the Disney/Pixar monolith still feels insurmountable. The Academy, much like America itself, relies on flashy displays of perceived progress without making fundamental changes that will transform them into the modern institution they claim to be.

The Academy’s ties to America will always stop them from being a true celebration of cinema. In order to survive, they must limit recognition for great art from around the world to maintain the idea that American art is superior. Can an institution claim to be the definitive beacon of quality when so many great filmmakers are excluded? As is tradition, American institutions will always look to impose their culture on the rest of the world without ever taking time to reflect on itself.

Best of Rolling Stone