The SPIN Interview: Taj Mahal

Taj Mahal flows effortlessly through his soundcheck at the Luckman Arts Complex, an elegant theater at California State University, Los Angeles. It’s only the second show of Mahal’s tour supporting Swingin’ Live at the Church in Tulsa, his latest live album with the Taj Mahal Sextet. But, at 81 years of age and over six decades of playing music, Mahal doesn’t need much preparation to perform.

The roots and blues musician is considered a national treasure. Besides winning four Grammys (and being nominated for 15), Mahal has been awarded several honorary degrees, including a Doctor of Fine Arts from his home state’s University of Massachusetts Amherst. For a lifetime of contribution to World’s history of Music, Mahal was given the United States Congressional Recognition Award, in addition to an Americana Music Association’s Lifetime Achievement Award. An inductee to the Blues Music Hall of Fame, he’s played with everyone from the Rolling Stones and Etta James to Eric Clapton, Bonnie Raitt, Wynton Marsalis, Morgan Freeman, and Keb Mo’. Among his numerous studio, live, soundtrack and compilation albums, there is even a collection compiled by one of film’s most revered directors: Martin Scorsese Presents the Blues – Taj Mahal.

Shuffling carefully off stage, Mahal settles into a straight-backed chair in his sparse dressing room. You won’t find an alcohol-and-junk-food-filled rider here. Instead, he has a tidy set up with a carafe of water and a small electric kettle, plus fresh ginger and lemon for his voice. As legendary a musician as Taj Mahal is, the fact that he’s clearly had an elevated upbringing is what stands out to me. He sips from a bottle of ginger beer as he enquires about my cultural background, how I came to write for SPIN, and if I’d like something to drink. His comfortable sandals-cum-shoes (his dress, or should I say “church” shoes, are tucked under the table), colorful jacket, beaded bracelet, fish necklace, and red bandana accentuate his down-to-earth energy.

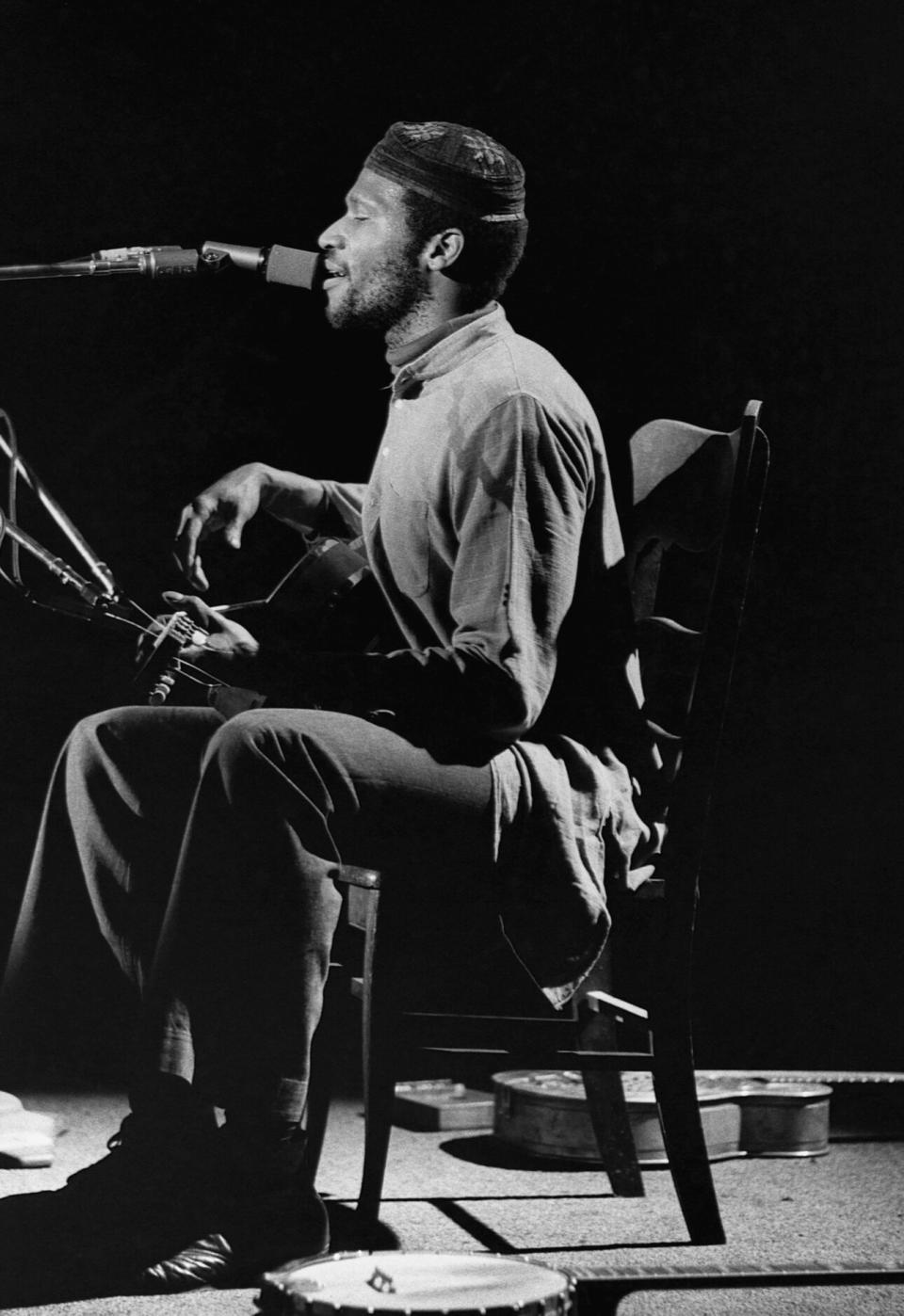

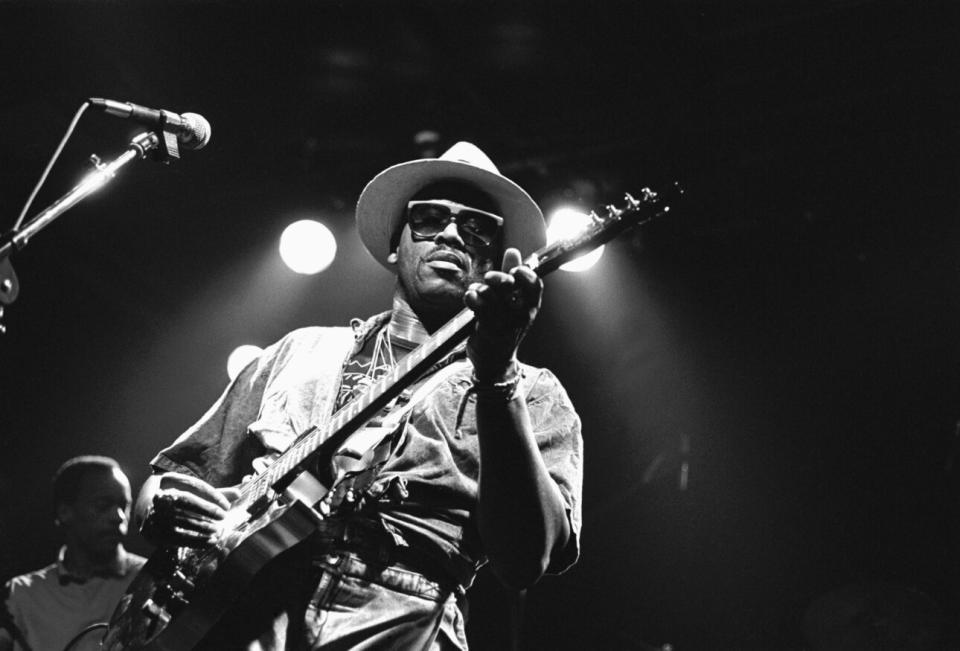

For tonight’s show, Mahal will change into his signature straw hat and shades, his hippie chic giving away to resort wear. He looks like he could be on holiday, but he’s hard at work. Positioned at the edge of the stage, he pulls from the guitars, ukulele, banjo, and dobro arranged around him in a circle. The riveted audience is seated, but every so often, someone—usually a woman—will stand up as if possessed and begin moving to the music. The diverse crowd is older and younger, dressed up and styled out, be it in fishnets or a sharp suit. These aren’t fans as much as acolytes. They know every song and movement, anticipate every word, and react to the emotion-filled performance almost involuntarily.

Mahal would be forgiven if he were arrogant and removed. He’s earned the exalted status he occupies. But he is warm and inclusive. He gives props to countless musicians during our conversation. His voice is a gravelly rumble, and he talks about farming almost as much as he talks about music, a throwback to his college days studying agriculture and animal husbandry. “I would have been glad to be a farmer and only play on Saturday night,” he says. “But the music started happening, and I started being able to make a living.” That hasn’t stopped Mahal from fashioning a farming analogy for almost anything. In the hour or so that he regales me with the stories he’s been telling for the last half-century, his phone dings incessantly. But he never looks at it, confirming once again that he was raised right.

SPIN: How did your family and upbringing influence you as a person and a musician?

TAJ MAHAL: My father was first-generation. His parents came from the Caribbean. My mom was from South Carolina. She was a Southern American woman but married outside that culture. Two Afro people, one from the United States and one moved here from the Caribbean, culturally, was different. They were really good together. Very smart people. It was an exciting childhood with lots of music and culture and food and people from all over the place. They gave us an incredible beginning, which opened us up to being connected to people globally. You got a feeling of the world, but I didn’t want to be wandering around from culture to culture. I wanted to be representing something.

My parents moved to Massachusetts because there wasn’t much work for my father. They wanted to raise a big family, so he went where the work was. That’s where I grew up, in a community with music and people coming from all over the place. My culture, other cultures, an amazing amount of humanity that worked together. Those years, the factories were working three shifts a day so men could come up from the South or the Caribbean or Italy or wherever, get a foothold, house, good schools. There was a lot going.

Your mother worked as a teacher in Massachusetts?

Yes. She had 40 years. The problem with guys is that they take their position for granted and they abuse that privilege. If you look at the Serengeti plains, you don’t ever see the males abusing their privilege with the women or vice versa. Only when you get into the agricultural sector is where it changes in America. Another place is Alaska. I was much more comfortable with the women there than the women in the cities. They could drive a tractor. They’re milking cows. They’re having kids, nursing a baby, cooking. Not that it has to be domestic. If agriculture is what we’re in, everybody helps. I grew up knowing lots of women who were professional but who handled everything else too, with glory.

My mother was a professional woman, as well as a gospel singer. She told my father, “We’re having fun, but what are we doing?” He said he wanted to have a big family. She said, “At some point, I’m going to want to go back to school and get my master’s degree. Are you willing to work and make that life easy enough for me to be able to do that?” He said, “Sure, but in the deal, I want a grand piano in the house.” He was a classically trained bebop piano player, played everything: swing, jazz, jump blues. He also bought a radio record player so he could play all the music. He said, “The music is always changing. I’ve got to keep up with the records.”

When did you start doing music?

Somewhere around 8 or 9. There were some interesting things going on in music that were being shared, the framework of the blues and the tone of other music that I could hear. One of the first albums I bought with my own money was called Port Said. Maybe it was the lady on the cover belly dancing that made me buy it, but I listened to it a lot. I was making a connection with the music. Music jumps in before the words do. I don’t know what the words are, but I know what I’m feeling. Eventually I knew it’s not just here in increments that are sold by big record companies. This is people’s history. I wanted to maintain it. That’s why I got into it, to keep bringing these little jewels out of the past and bring them forward. I found out that’s a particular way that certain African people do. They reach back every now and then, bring something good, put it on the table, and everybody says, “We’ll do that again.”

It seems like unlike most people, you skipped popular music and went straight to the origins.

Yes. By the time rock and roll came, I had already heard the imprint that it came from as a complete music. I was like, “Why are you so excited about this? This is the stuff over here. Why don’t you get excited about that?” But it’s what people wanted.

What pushed you in the musical direction you went in?

It was the water I swam in. From this perspective, I could see I was really surrounded. I was deep in the water of the music. When I started, it was really important to play for myself. Then I had some opportunities to join different bands. I knew a lot of music to play. Those guys didn’t know the origins of the music. I would bring them songs I would think they knew, and I had to teach them the songs. We ended up having bands that sounded so different. They were oriented toward: “It’s on the radio, therefore it is.” I was like, “It’s in the universe, therefore it is.” I realized if it wasn’t somebody else’s music, I didn’t really know the music or the tradition or any of the people who were in it. That’s when I started buckling down and paying attention.

Can you pinpoint some musicians from whom you learned?

The beginnings of playing guitar [came] from my next-door neighbor who came from North Carolina. Then my neighbors up the street who are from Mississippi. I didn’t learn to play none of their tunes, but I watched them play. It had nothing to do with sitting down with notes and being taught by some professor somewhere. I had two weeks of formal training on the piano. The woman told my mother, and I quote, “Mildred, I wouldn’t waste my money on that boy. He already playing boogie-woogie.”

You get inspired by people who say “I watched so-and-so and learned. So-and-so showed me how to play this song.” When you get that song, that’s a key that gets you on the inside. From there, you expand. When I first learned to play, it was very different. I still play exactly what I learned. But I got more and more interested in the guitar. I target what I want. I get on and keep learning. At my age—I’ll be 82 my next birthday—I’m still learning.

What brought you to the West Coast?

Ry Cooder. I heard his ability to be able to teach and play music through another musician. I was just struck because it was the real music. I asked, “Where did you learn to play music like that?” He says, “This guy named Ry Cooder out on the West Coast.” I’m like, “Wow. You think that guy would like to be in a band? Can we get him out here?” He says, “I don’t think so. He’s 17 years old.” I said, “We’re going to California.” Just like that we came. Within two or three days of me being here, I met him and in no time we had the band Rising Sons together. I was 23. Ry was playing like a grown man. That was the whole thing I couldn’t get out of these other musicians. They were happy to imitate what they heard. Some very good. Others even better. But Ry heard the music and he put himself in the music. He is a very creative musician, loves a lot of different types of music. We have similar interests.

What was it like out here at the time?

It was really different for me because I came from the East. But there were some places where people really played the real music. The Improv on Melrose used to be the best music club in Los Angeles for roots music, Ash Grove. Lightning Hopkins, Judy Wells, Georgia Monica Smith, Big Mama Thornton, the Chambers Brothers. It was a good scene. People knew what the music was. It was not the popular music. Popular at that time was Sonny and Cher “I Got You Babe.”

Pretty soon it got to be an incredible scene with Love, the Byrds, the Flying Burrito Brothers, the Wrecking Crew. It was a lot going on. There was emphasis on the commercial side. I didn’t particularly care for some of the studio musicians. They wouldn’t touch some of it because it wasn’t commercial enough. It was how they were making their living. I didn’t want to take my song and give it to the studio musicians. They put it out. It becomes a hit. Then you have a band copying your music. Here’s a band. We go into the studio. We make this music. We go on the road, and we play it. That’s all I know.

Knowing what you want and sticking with it from so early on, that is something that is difficult for a lot of musicians.

Making music, that’s why I came into it. My ancestors, my DNA, my culture, all these things contribute to me being honorable toward that culture and representing. I’m not letting it down. This is what we do.

What were your experiences with the Rolling Stones like?

They were big stars, but they came to the Ash Grove. They’d be rapt and having a wonderful time: meet, take pictures, and just so excited. This is why the Stones are still there because they get in the real part of the music, and they always knew it. They were always inspired by it. They didn’t just grab it and turn around and run forward.

We collided when we were playing The Whisky a Go Go. I looked down off the stage, playing my harmonica, and I said, “Wait a minute, that’s Mick Jagger dancing; that’s Keith Richards; that’s Brian Jones. Over here is Eric Burdon and Hilton Valentine.” They’re all dancing and grooving. I said to myself, “When you get off this stage, you need to go talk to those guys.” I can tell you exactly what I said: “Listen, let me tell you something. I don’t know what you got in the water over there, but if there’s any projects that you’ve got that you think we can be a part of, don’t hesitate to call.” Four months later, eight first-class tickets BOAC, Los Angeles to London. Unbelievable. I’ll use a correct English term, “whilst” there, I never stuck my hand in my pocket for anything other than chewing gum, cigarettes, postcards, or gifts to bring home. They gave us everything. If there was royal treatment, we got it from the Rolling Stones.

There is an entry for you in the Encyclopedia Britannica. It says you created what’s now known as “world music.”

It didn’t have a specific name that they could focus on. I didn’t realize I had that ability to hear, to listen globally because I come from everywhere. When I’m listening in South America: tango, samba, choro, all have their roots in Africa. Candomblé, mambo, bachata, salsa, they all have their roots in Africa. I’m just playing the music from those perspectives.

You’ve had musical overlaps with children’s books and songs. How did that come about?

As a kid, we all heard Disney stuff on records. The story that you knew in the cartoon, that you knew in the book, had a musical component to it. I realized that if I ever got a chance, I would like to do some music for young kids. I would have been able to do an awful lot if I heard certain kinds of music as a kid. What happened in the ‘80s was I had a lull. The last major record company I was with was in the ‘70s. From then it was one-offs, two-offs. The ‘80s came in and I didn’t have a contract, so I thought now is a good time to do some of that stuff like children’s music, so I got busy.

It’s like farming. That field has been lying fallow for a bunch of years. Let’s get in there and get it plowed up and get some fertilizer, get something going. Somebody pointed out to me that I didn’t go into farming, but I farmed music. That’s not a bad point.

Is that also how the literature overlap happened with Langston Hughes’ and Zora Neale Hurston’s Mule Bone?

That was an interesting project. I had never read anything that had to do with farming. I came upon Zora Neale Hurston. She did a book called Mules and Men. I was taken by this woman. She was one hell of a writer.

One day they rang me from the front desk of a hotel saying, “There’s a gentleman here with his son. They would like to have you come down.” He put him on the phone and said, “I was the last secretary to Langston Hughes. He and Zora Neale Hurston had written a play, which had not been done for 60 years. They’re getting ready to put it on Broadway. And we would like you to be the person to do the music. We can’t think of anybody else.” I came down, and this guy had a book that was that thick of Langston Hughes’ poems and writings. “At your leisure, put these poems to music.” So I got busy and had big fun doing it.

I got to stand off the stage and hear the music play. I put the band together. I brought Kenny Neal, who was a guitar player from Louisiana. It would be terrible to have some actor that doesn’t really know how to play guitar be on stage. I hustled this guy in there. He got to be the lead in the play. It ran for about nine months at the Ethel Barrymore Theatre. So many nights, for the first time, I was off the stage listening to the music that I’d written.

You have a new live album that was recorded at The Church in Tulsa, the home of Leon Russell. How did that come about?

A woman that’s coming to the show tonight, her name is Claudia Lennear. She used to be one of the Ikettes. She also was part of 20 Feet From Stardom. She also went on the road with Joe Cocker. She’s “Brown Sugar” to Mick Jagger. She got called by Teresa Knox, who runs out the studio down there in Oklahoma. She came down and did a show, and she was just knocked out. They started talking. She brought my name up. Teresa said, “Do you think he would want to come down here and do a project?” Claudia talked to me. I was recording with a sextet, and I said, “If we can get a gig there, that will be the perfect way.” Because we wouldn’t have to have a gig and then stop and record. While we’re doing the gig, you keep recording then you get it in the early stages of being put together. There’s something there that’s magic.

To see our running list of the top 100 greatest rock stars of all time, click here.