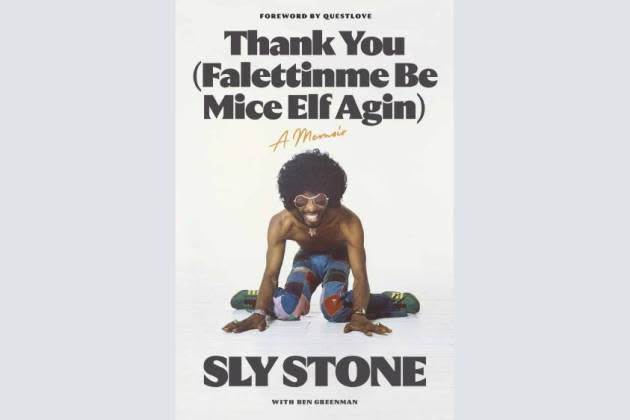

Sly Stone Returns With Alternately Riveting and Horrifying Memoir, ‘Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin)’: Book Review

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Of all the fallen stars of the rock era, Sly Stone is definitely in the top 5 who seemed least likely to be writing an autobiography at 80 years old.

As the founder and guiding light of Sly and the Family Stone, he was one of the most brilliant stars of the Sixties, a charismatic and pioneering musician who not only fronted the first major multi-genre/ multi-racial/ multi-gender band, but whose songs addressed the turmoil and the spirit of the era and, initially anyway, landed on the side of positivity and self-empowerment: “Everybody Is a Star,” “You Can Make It If You Try,” “Everyday People,” “Stand!,” “I Want to Take You Higher.” He and the group were undisputed pioneers of funk, rock and soul music (and later became one of the most sampled artists in hip-hop history), and their electrifying performance at Woodstock turned them into one of the world’s biggest acts. But as the decade turned, things grew dark when drugs, guns and violence entered the picture; the music got darker too, especially on the fiery “There’s a Riot Goin’ On.” Sly managed to keep his star aloft for a few more years — 1973’s “Fresh!” is one of his best albums — but the long downhill slide had begun, and by the late ‘70s he was broke, addicted and adrift — and for the most part, he remained that way. There have been several aborted comebacks, all of them disasters entirely of his own making.

More from Variety

'Grammy Salute to 50 Years of Hip-Hop,' Helmed by Questlove, Airing in December

Questlove to Write 'Hip-Hop Is History' Book for Rap's 50th Anniversary (EXCLUSIVE)

Ryan Coogler, Questlove Announce New Projects With Onyx Collective for Hulu

So this book, written by a recently-sober Stone with the New Yorker’s Ben Greenman (and the first release from Questlove’s AUWA Books), is not only a welcome surprise, it’s written in a voice that will be so familiar to fans that its first few chapters are like a visit from a long-absent friend. Sly writes like his lyrics — the offhand rhymes and playful turns of phrase, some of which are funky but quaintly dated (“How many bellboys got their bells rung”), others timeless (“When I was old enough to not be too young anymore…”). Its tone and pacing mirror Sly’s life, too — the first few chapters are electric and exciting, following his upbringing in Vallejo in the San Francisco Bay Area and rise as a precocious church musician (his first record, also featuring his siblings and future bandmates Rose and Freddie, was a gospel single released when he was 13), then his rise as a radio DJ and a successful record producer in early ‘60s San Francisco — including dates with the Great Society, producing songs that would later become world-famous after that group’s singer, Grace Slick, joined the Jefferson Airplane.

He details the Family Stone’s formation — when seeking a drummer, he wrote, “I had rhyme, I had reason, I needed rhythm” — and its gradual rise, and how he was able to make its message more palatable by dialing back the complexity of the group’s 1967 debut, “A Whole New Thing,” by bringing “the catchiest melody, the most obvious rhythm and the simplest words” into their first hit single, “Dance to the Music.” The group reaches the top with 1969’s epochal “Stand!” album and culture-shifting performance at Woodstock (not to mention the Harlem Cultural Festival a couple of weeks earlier, immortalized in Questlove’s “Summer of Soul” film), until there’s almost nowhere left to go except down.

And as part of rock’s first wave of superstars, Sly indulged in just about every excess until they nearly destroyed him. While friends like Muhammad Ali, Doris Day and George Clinton make cameos during these years, the accounts of the excesses of his too-high years (included in Joel Selvin’s 1997 Sly-less oral history of the band and multiple articles and documentaries) are filled with accounts of guns, aggressive bodyguards and even more aggressive attack dogs — one of which, named Gun, Sly himself killed after it badly mauled his son. He calls the dog the best friend he ever had.

In the book, Sly is direct about his bad turns but not particularly sorry, either — and here his much-vaunted dark side shows itself, if only by his matter-of-fact, unemotional descriptions of truly horrifying events. However, he nods to it in clear-eyed terms early in the book, calling it the “flipside of this bright and stirring story” of his success: “The young boy, now a young man, facing into the harsh light of fame; the young man, now a star making his way through a house crowded with drugs and guns; the star, now letting his light be crowded out by those drugs and guns.”

But later, he’s upfront and unapologetic about his drug use, at-times erratic behavior and run-ins with the law (which resulted in jail stints for drug, child-support and tax offenses) but downplays the extent of his notorious, multiple last-minute concert cancelations and his security staff’s threatening behavior. He later speaks of these incidents, as well as things like not seeing his daughter for several years or failing to pay people, without much emotion; even when he finally gets sober for good, after a fourth hospital stay, he’s unrepentantly straightforward about it: “It wasn’t that I didn’t like the drugs,” he writes. “If it hadn’t been a choice between them and life, I might still be doing them. But it was and I’m not.”

As exciting and life-affirming as the book’s early chapters are, the second half is tough — first watching him lose everything, then reading his dry accounts of addiction, multiple stints in jail and peripatetic existence. Through it all, he was apparently working on music that few people have ever heard — he’s released just a handful of songs since his last full album, 1982’s “Ain’t But the One Way.”

The book does finish on an up note — he speaks of how much he owes to his current manager Arlene Hershkowitz and how she stayed with him through multiple ups and downs (mostly downs), and writes happily of being reunited with his family, children and grandchildren, who appear in several recent photographs in the book. And although there are no plans to release that aforementioned long-percolating music, there’s more in store: Questlove not only published this book on his new imprint and wrote the introduction, he’s also helming a Sly documentary that will probably see release next year.

It seems that after so many years in the wilderness, Sly is finishing on an thankful and thoughtful note.

Best of Variety

Sign up for Variety’s Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.