Sixto Rodriguez: Life After ‘Sugar Man’

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

On what should have been the biggest night of his life, the 70-year old singer-songwriter Sixto Rodriguez was, once again, nowhere to be found. Searching for Sugar Man, the blockbuster 2012 documentary that finally, miraculously introduced his music to the world, was about to win the Oscar for Best Documentary. But Rodriguez hadn’t just skipped the ceremony at L.A.’s Dolby Theatre. He was back home in Detroit, sleeping. “I missed the program,” Rodriguez says “We just came in the day before from South Africa. My daughter Sandra called toto tell me. I don’t have TV service anyway.”

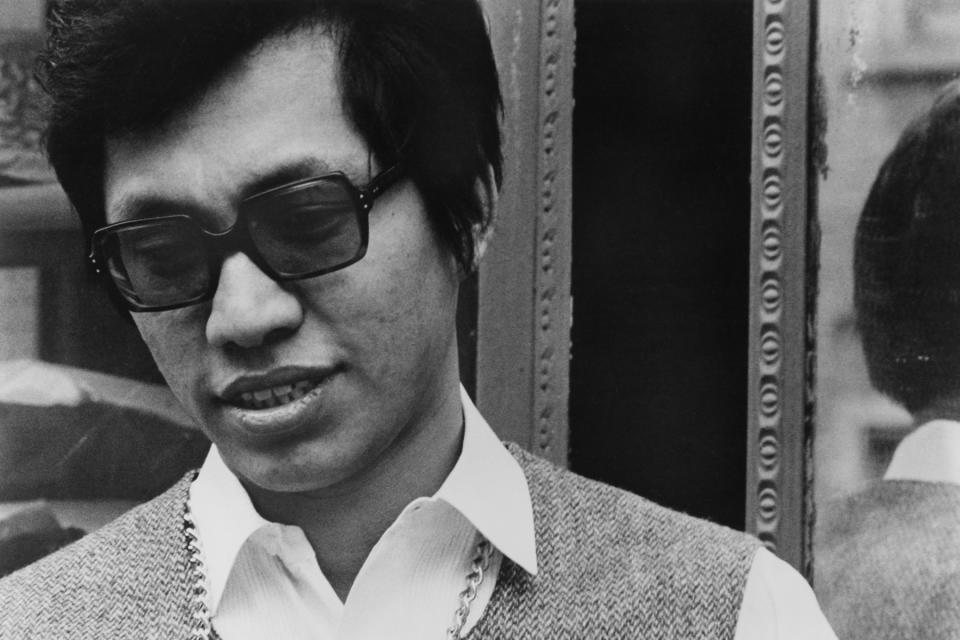

Two weeks later, he’s giving a tour of Detroit where he’s lived his entire life. “Let’s just cruise around,” he says, sparking the first of several joints, which he smokes both for recreation (he calls it “puffing the magic dragon”) and for pain from the glaucoma that has made him virtually blind. “I don’t want to attract the attention of the police.” Rodriguez is squeezed into the back seat of a silver Jeep Laredo with his girlfriend, Bonnie — up front are his pregnant daughter, Regan, and, at the wheel, her husband. It’s an unusually warm late-winter day in Detroit and Rodriguez is dressed in all black: leather pants from London chunky sunglasses, a sharp sport coat and a choker with a Native American wooden eagle on it. His hair, perhaps suspiciously, doesn’t have even a hint of gray. “This stuff isis all about my image,” he says “Its an act.”

More from Rolling Stone

After four decades of near-total anonymity he hasn’t made a record since 1971, and earned his living doing construction and demolition work. Rodriguez has become a certified superstar. His shows, which sell out instantly, have grown over the past year from clubs to a date this fall at at Brooklyn’s 19,000-capacity Barclays Center, usually home to the Nets and Jay-Z concerts. In his hometown fans swarm him everywhere he goes. When we stop at a coffee shop on the Wayne State University campus (where Rodriguez got a philosophy degree in 1981), a female fan immediately buttonholes him. “We tried to get tickets toto your show, but it sold out,’,” she gushes. “Next time, book Joe Louis Arena!”

Despite his newfound financial fortune — he grossed more than $700,000 for five recent shows in South Africa — Rodriguez continues to live as he always has. He doesn’t own a computer or a car, and has no interest in acquiring either, and he’s staying put in the same house he’s lived in since the early 1970s. “He lives a very Spartan life,” says his daughter Regan. “I almost want to say Amish. Most of the money he’s just giving away to friends and family. I really wish he’d spend it on himself.”

We eventually pull up to Detroit’s Masonic Temple, a gorgeous neo-Gothic building that has hosted everyone from the Rolling Stones to Bruce Springsteen. Rodriguez is playing there for the first time in his life, in May. He’s two days away from launching a world tour, which start in New Zealand and Australia and has more than 40 major shows booked, including stops at Coachella and Glastonbury. “The money, i have to admit, is obscene,” says Rodriguez, before breaking out into hysterical laughter. “I have a lot of commitments, and the list keeps growing. We have to strike while the iron is hot.”

The career that’s finally booming nearly ended before it had a chance to begin. In the mid-1960s, Rodriguez began playing Detroit coffeehouses, and eventually recorded two folk songs in 1967 under the name Rod Riguez. “It was the producer’s decision,” he says of the name change. “He thought it would be more attractive.”

As the Detroit rock scene exploded around him — the Stooges, the MC5 and Bob Seger all got their start around this time — Rodriguez played his songs at bars with names like the Sewer while working at an industrial laundry at night. “I saw him at this place called Anderson’s Garden,” says Mike Theodore, who went on to co-produce Rodriguez’s 1970 debut LP, Cold Fact. “It felt like a whorehouse. The bar was full of prostitutes, and there was Rodriguez up there singing. He was playing with an organ player, and a saxophonist with no teeth.”

He wasn’t the most dynamic live performer around, almost always playing shows while facing the wall. “I had to learn how to work these small rooms and get more confidence,” he says. “I don’t eyeball my audience, like the way a rap artist does who is more confrontational. I get more in tune with my eyes closed, and I listen to the song so I can re-create it.”

When Motown exec Clarence Avant signed Rodriguez to his new Sussex label, he thought he had a major star on his hands. “Honest to God, I thought this guy was going to be huge,” says Avant. “He’s one of the three greatest artists I’ve ever worked with, and that includes Bill Withers. He was a fucking genius.”

But a showcase for concert promoters, record executives and other industry bigwigs in L.A. was a fiasco. “He was plas-tered, and he turned his back to the audience,” says Avant. “Nobody dug that. It was like a Miles Davis thing. The reaction was an absolute zero. No, make that subzero.”

The follow-up, 1971’s Coming From Reality, also tanked, and that was it for Rodriguez’s music career in America. Strangely, Australia was a different story. After a DJ in Sydney began playing “Sugar Man” in 1972, Cold Fact became an unlikely hit. “Every single one of my friends had Cold Fact,” says Midnight Oil drummer Rob Hirst. “We’d play records by Bruce Springsteen, Billy Joel and Rodriguez.”

The last blast of his pre-revival career came in 1979 and 1981, when he was booked to tour Australia. “He had never played a concert before, just bars and clubs,” promoter Michael Coppel told Billboard at the time. “He was just stunned by what was being put together for him.” When he returned in 1981, he shared a bill with Midnight Oil. “I thought it was the highlight of my career,” Rodriguez says today. “I had achieved that epic mission. Not much happened after that. No calls or anything.”

At the same time (as Searching for Sugar Man documents), South African fans discovered his music, and his two LPs were reprinted there. Rodriguez was unaware of his fame, and by the 1980s, he had left music — although he never gave up hope that he might return to the stage. “He took me and my sisters to the library every single week to read the new issue of Billboard,” says his daughter Regan. “He’d show me all the stats in Billboard, and the [concert box scores] from Pollstar. He’d talk about how lucrative the concert industry was if you could get there. He never said it out loud, but the dream was still there.”

In what would have been yet another near miss for Rodriguez, he considered not participating in the Sugar Man movie. In 2008, Swedish filmmaker Malik Bendjelloul contacted Rodriguez with an idea for a movie about his fame in South Africa, which climaxed with a series of sold-out Cape Town shows in 1998. Rodriguez declined the interview request until Bendjelloul had visited Detroit three times. “He felt sorry for us,” says Bendjelloul. “He was like, ‘I better help these people out because they’re crazy.’ He did

it out of kindness.”

After picking up a work visa for the Australian tour, we head over to a friend’s house. As her father hangs out on the patio smoking another joint, Regan reflects on how crazy their life has become since the movie came out. “All of a sudden I’m hearing from friends that I never knew were my friends,” she says. “Everything has been real positive, but we haven’t gotten him a manager because ‘manager’ has always been a bad word in our house.”

For the shows he plays now, Rodriguez doesn’t have a regular backing band — instead, groups of often famous musicians back him when he comes to town. In Australia, members of Midnight Oil are handling the dates. “He only wants to rehearse for a couple of hours, so we’ll be flying by the seat of our pants,” says Hirst. “It’s going to be such a thrill.”

As we swing by Michigan Central Train Station — a glorious abandoned 1913 structure every bit as stunning as New York’s Grand Central Terminal that now sits alone in the middle of an empty field – Rodriguez breaks out into applause. “Wow!” he says. “How many years now has it been closed? Thirty years!”

His former producer Theodore would love to get Rodriguez back into the studio but knows how unlikely that is. “Imagine the pressure he’s under now,” he says. “I don’t even know if he wants to go out there and promote a third album. Besides, most people are only now hearing his old songs. He once told me that he would write 30 songs and they would take him around the world. You know what? He was right.”

Best of Rolling Stone