In the Year Since the Taliban Took Back Afghanistan, Women's Rights Have Been Erased

WAKIL KOHSAR/AFP via Getty

It's been one year since the Taliban regained control of Afghanistan and began issuing restrictive decrees for women — despite promises they wouldn't.

On Aug. 15, 2021, two weeks before the United States withdrew its troops from Afghanistan, the long-overthrown Taliban took back power of the Asian nation, creating fear about what it would mean for Afghan minorities and women. Without hesitation, the oppression commenced.

First, lists of unmarried women between the ages of 12 and 45 were compiled for Taliban fighters to marry. Next, women were advised to stay home from work for their own safety. Secondary school and higher education for girls were closed.

As the months went on, the Taliban issued more than 30 decrees following a strict interpretation of Islamic law. Television shows that included actresses were banned, including soap operas and dramas. Women were forbidden to take solo road trips longer than 45 miles, and were banned from visiting women's health centers without a chaperone. They also can no longer obtain driver's licenses, take taxis without chaperones, or sit next to taxi drivers. In addition, women must cover their faces in public, only showing their eyes, and the Taliban recommends they wear the head-to-toe burqas.

The Taliban even declared that women would not be able to refuse marriage — in a country with rampant domestic violence issues.

In Herat, one of the largest cities in Afghanistan, women have no right to sue men, and cannot attend Friday prayers at mosques. They are banned from cafes unless they are with a male companion.

Acceptable jobs for women include health care and teaching — though with secondary schools and universities closed to girls, many teachers are out of work. Women can be security guards at the airport to frisk female passengers, and can work in television news if they wear headscarves.

Leaving the house is risky and unpredictable.

"It's not like if there's an order then everybody does that. That's not the way it works. There are some foot soldiers that just walk away and don't do anything, but there are some that really beat these people up," says Afghan author, filmmaker and social entrepreneur Nahid Shahalimi, who spoke to PEOPLE from Canada.

Ying Tang/NurPhoto via Getty

"For many women across the world, walking outside the front door of your home is an ordinary part of life," said Alison Davidian, Afghanistan representative at UN Women during a recent press briefing. "For many Afghan women, it is extraordinary. It is an act of defiance."

"Some women told me they still go to the market without a mahram (chaperone), but they live in fear that one day they will be stopped and beaten for the act of buying groceries without a man. Some women also told me that Afghanistan feels safer now — they're less afraid of indiscriminate attacks and relieved the conflict has subsided. But safety comes at the expense of agency — and this price is too high for most women," Davidian said.

RELATED: As Taliban Promises More Rights and Peace, Experts Warn of a 'PR Machine' in 'Overdrive'

Presently, 20 million girls and women mostly stay home, erased from public society. "They can't do anything, literally. They're not even allowed to go on the streets without having a good reason," Shahalimi says. Foot soldiers are permitted to stop them and ask why they are out — and if they don't like the answer, they whip the girls. Male family members deemed responsible for the girls can be jailed for the offense, too, she notes.

Feeling hopeless, teenage girls are committing suicide, says Shahalimi. "It is a very bleak sight." According to her, learning by computer is seldom available — only the "lucky" have generators that provide electricity and computers that can access internet. Even with those amenities, they would have to be able to afford internet service, and 25 million people in the country are "on the brink of starvation."

"Marriages of young girls have skyrocketed like there's no tomorrow because parents cannot feed their children," adds Shahalimi. "If you can't feed your child then you're going to sell her to somebody for 500 bucks. They give you 500 bucks, at least you have two months' worth of food for the rest of the family and that girl gets fed by the other man."

RELATED: Malala Yousafzai 'Deeply Worried About Women, Minorities' as Taliban Seizes Power in Afghanistan

In addition, the Taliban has crushed the country's culture. "They're robbing Afghanistan of its soul. Afghanistan is a colorful country, beautifully draped in various colors, the languages, the music, the poetry, arts, all of these things has always flourished, that is the soul of the country, and they have completely robbed the country out of its soul. There is no art, music is banned, completely banned," Shahalimi says.

Sajjad Hussain/AFP via Getty Afghan women take part in a gathering at a hall in Kabul on Aug. 2 against the claimed human rights violations on women by the Taliban regime in Afghanistan.

The Taliban dissolved Afghanistan's Independent Human Rights Commission. The Ministry of Women's Affairs is gone and there are no women in the cabinet of the de facto government. Now women have no right to political participation.

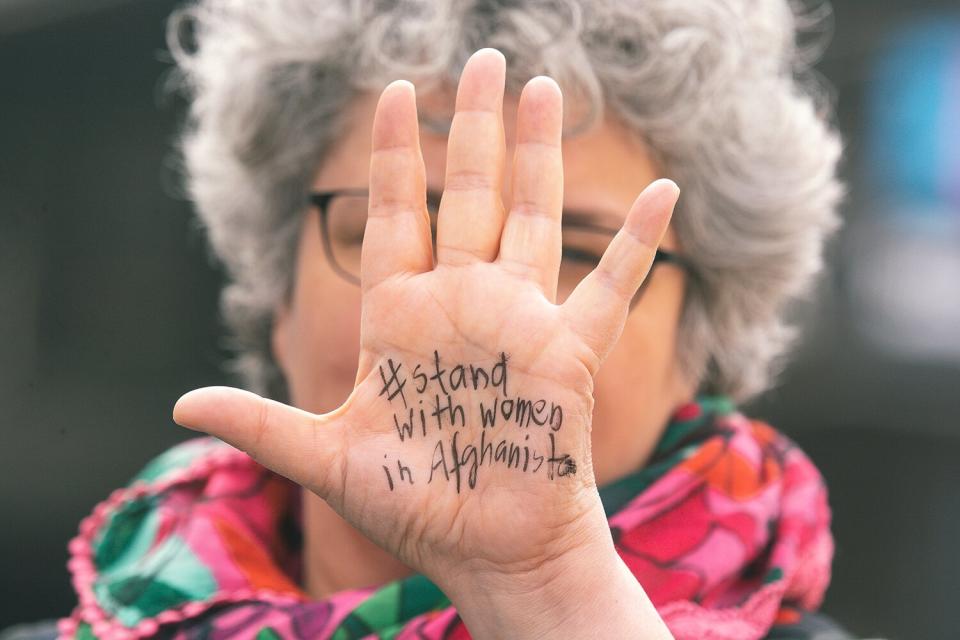

Small groups of women have protested, but when four women were arrested for protesting against the headscarf mandate in January — with armed gunmen forcing their way into the women's homes to take them — women learned the danger of speaking up.

In March, school was set to reopen for girls, but hours after the opening the Taliban shut them down again. About two dozen girls and women bravely staged a protest, aware of the potential consequences. This past week, about 40 women at a protest in Kabul chanted "bread, work, freedom," "we want political participation" and "no to enslavement." They were disbursed by Taliban soldiers, who reportedly fired shots over their heads and beat some participants.

RELATED: Women Protesting in Afghanistan Stand Face-to-Face Against Armed Taliban Fighters

Women's rights activists have been trying to help from the outside. Razia Barakzai, who initiated the first women's protests in Afghanistan after the fall of Kabul, saw her group threatened with rifle butts, pepper spray, tear gas, electric shock and whips.

She created the hashtag #AfghanWomenExist and she and dozens of other female activists are still working from outside the country. Shahalimi, who is living in Germany, set up scholarships for young women to study for jobs in healthcare through her social impact company, We The Women. There are also reports of small underground schools, but those efforts are only reaching a small number of girls.

Breathing hope into this dire situation is hard. Shahalimi has just published a book, We Are Still Here, lifting the voices of Afghan women. She runs empowerment sessions for her scholarship students, advising them, "Whoever is close to you, pick them up, in whatever way, shape or form you can. If it's giving them an hour of your free time, just teach them something. That is what gives them hope."

RELATED: Taliban Target Malala Yousafzai: I Have Not Changed

Husna Jalal, a women's rights activist living in exile in the Netherlands since last August, was born during the first rule of the Taliban in the 1990s. When the international community got involved after 9/11, girls and women were given opportunities in school and in the workplace. Women still had to navigate a patriarchal society, putting up with "mansplaining, sexism, and misogyny," she says, but "we still had the right to go out and fight for our rights."

"I'm extremely hopeless seeing the situation and seeing the world not taking any action," Jalal says. "It is really heartbreaking. I don't know how long it will take for the world to impose restrictions. The U.N. and the EU are interacting with Taliban, trying to find ways to reach a consensus, but we don't see any result."

Never miss a story — sign up for PEOPLE's free daily newsletter to stay up-to-date on the best of what PEOPLE has to offer.

The world seems to have forgotten Afghanistan. "International fatigue had kicked in in Afghanistan way before the 15th of August" last year, when the Taliban took over the country, says Shahalimi. "That's why three or four weeks after (the Taliban takeover), everybody forgot Afghanistan."

For things to get better with Afghan women and girls, Shahalimi would like to start with an equal number of women included in international delegations for talks with the Taliban. All-male delegations "normalize that it is okay not to have a woman in your delegation," she says. "Even if the Taliban don't address the women, start with that."