This simple at-home test may help detect subtle signs of dementia

Though not unusual, a memory that fades with age can be worrisome: while it’s just a normal part of aging for some, for others it may be an early sign of a more serious problem, such as Alzheimer’s disease. A new study suggests that a simple test that anyone can take on their own may be able to detect subtle signs of dementia earlier than currently used screening tests.

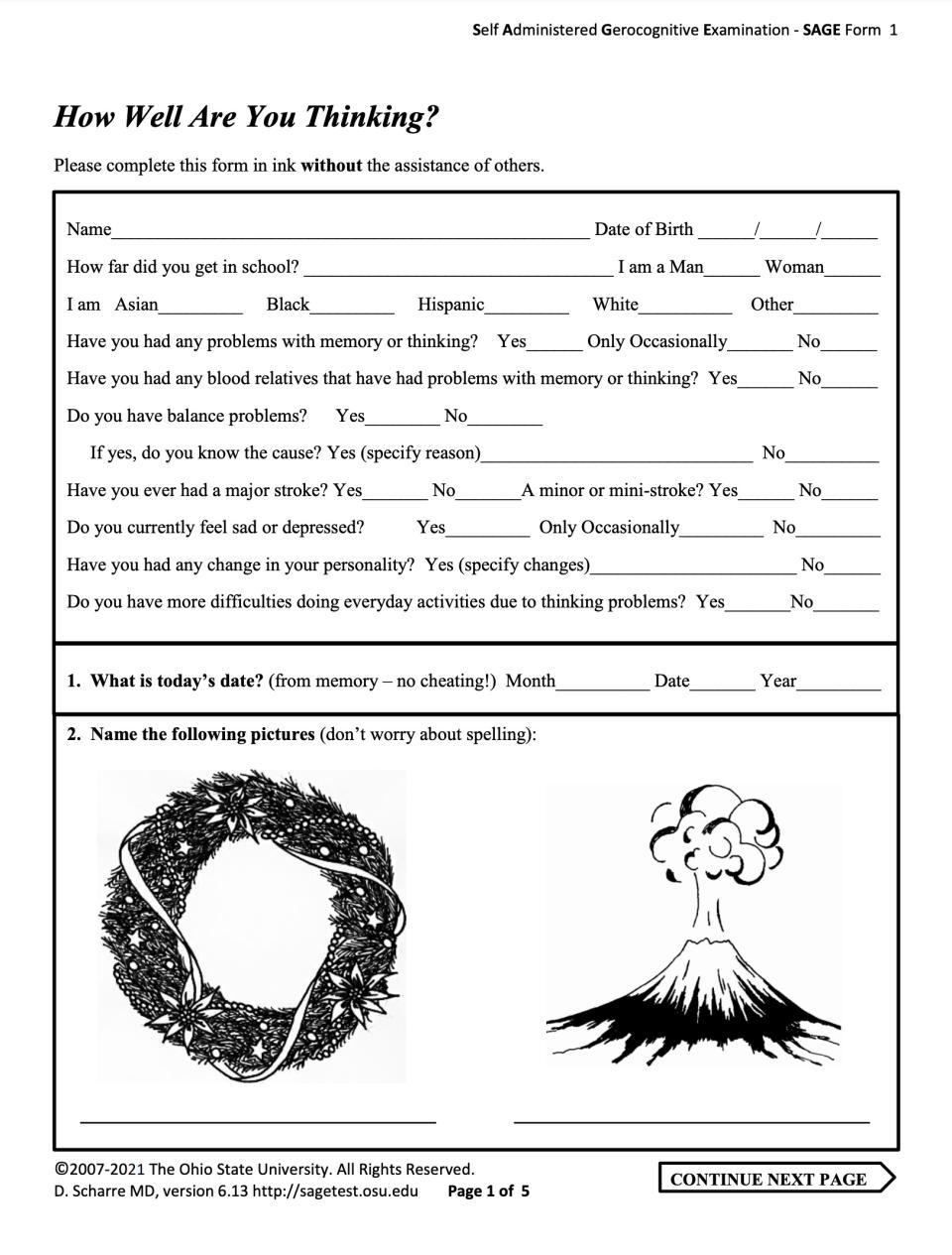

Researchers assessed the accuracy of a paper and pencil test, dubbed SAGE, in more than 400 patients who were followed for nearly nine years and found that when results from different points in time were compared, age-related memory loss could be distinguished from the early stages of dementia, according to the report published in Alzheimer’s Research and Therapy.

“We found SAGE to be an effective screening tool to identify people who would eventually develop dementia, probably six months earlier than the most used screening tool,” said Dr. Douglas Scharre, director of the division of cognitive neurology at Ohio State University.

One big advantage of SAGE is that people don’t need to be supervised while they pencil in the answers, Scharre said. “Patients can take it on their own while they are sitting in the doctor’s waiting room,” he added. “Since you don’t need someone to administer the test, such as a doctor or nurse, it’s easy to have patients do it every six months.”

The new study pinpoints how much of a score drop will indicate the subtle signs of developing dementia, Scharre said. “What we suggest is that if you take it at home, you bring it to your doctor to score it,” he added. “If today’s score is normal, you want to check again in six months to see if there is a decline. Our study showed that only people whose scores dropped eventually developed dementia.”

For those who like to figure out stuff on their own, it’s possible to download the test and learn how to score it via the SAGE’s physician's section. Scharre notes that there are four different versions of the test so people won’t get a boost from remembering what was on the exam the last time they took it.

To see whether the SAGE test could distinguish between normal age-related memory loss and the memory problems tied to dementia, Scharre and his colleagues reviewed the charts of 665 consecutive patients who had come to the Ohio State Memory Disorders Clinic. The researchers included patients in their analysis who had had at least two visits six months apart during which they were evaluated with SAGE and the current standard, the Mini-Mental State Examination, which must be given by a health professional.

Of the 424 individuals who fit the criteria for inclusion in the study, 40 were determined to have subjective cognitive decline (patients who felt their memories were getting worse, but they still tested in the normal range), 94 had mild cognitive impairment that did not convert to dementia, 70 with MCI did progress to dementia and 220 were found to have dementia on their initial visit.

Among patients who eventually progressed from MCI to dementia, scores dropped 1.91 points per year on the SAGE test and 1.68 points per year on the MMSE. Among the patients whose initial scores indicated Alzheimer’s disease dementia, SAGE scores dropped 1.82 points per year and MMSE scores dropped 2.38 points per year. Scores remained stable for patients who had subjective cognitive decline and those with MCI that did not progress.

“I think that the idea of trying to identify one’s own personal cognitive decline over time is excellent,” said Sandra Weintraub, a professor of psychiatry in the Mesulam Center for Cognitive Neurology and Alzheimer’s Disease at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine. “This is a topic that's been of interest to all of us in this field for a very long time.”

Weintraub believes the future of dementia detection is online cognitive tests that you can bring up on your phone to see how you are doing over time.

Overall, though, such tests, whether pencil and paper or their digital cousins are “a great idea,” she said. “One of the problems we have is when a person comes in for cognitive evaluation, we don’t know what they were like before. Everyone is different.”

People should look at cognition checks the same way they look at blood pressure monitoring, Weintraub said. “If your blood pressure is high, you call your doctor. The same should happen if you see a decline on a ‘brain monitor.’”

It’s important to understand, though, that the results of these tests are not a diagnoses, Weintraub said. That’s because a lot of things besides brain changes can lead to cognitive decline, some of them curable.

For example, she said, “older people can have this kind of decline due to kidney failure. You have to remember, the brain is a chemical/electrical organ. There are certain neurotransmitters the brain needs and when you have kidney failure or any kind of organ issues the chemistry changes.”

The good news, Weintraub said, is if your declines aren’t caused by actual changes in your brain, they maybe reversible.