Sheriff David Mamet Lays Down The Law: “No Talking *After* The Show”

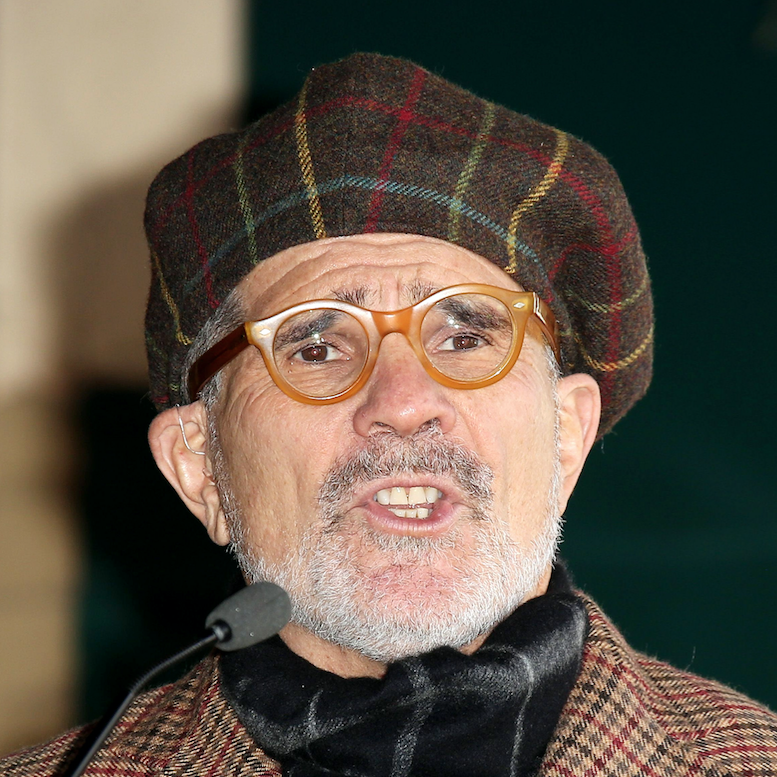

Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright, Oscar-nominated screenwriter and inveterate polemicist and provocateur David Mamet is suddenly the talk of the rialto on both sides of the Atlantic. Why? His revised licensing contract through the Dramatists Play Service now includes a clause prohibiting producers from offering talk-backs within two hours of a performance. Violators risk the loss of the license and a fine of $25,000 for each offending session. Long a fixture of off-Broadway and resident theater shows, talk-backs have also become increasingly popular in recent years on Broadway, where audience engagement has become a common goal.

I posted news about the clause under the heading, “Another free-speech beneficiary shuts down free speech and the exchange of ideas.” That led to an extraordinary exchange, mostly on FaceBook, among several artists with deep Broadway and Hollywood connections: Tony-winning writer Doug Wright (I Am My Own Wife, Quills, War Paint); Tony winning producer and director Gregory Mosher, who staged the world premieres of 23 Mamet plays, as well as the original Broadway productions of Glengarry Glen Ross and Speed-the-Plow; veteran stage and screen actors Patrick Page (Spider-Man Turn Off The Dark, Madame Secretary) and Peter Gerety (Sneaky Pete, Mercy Street, Lucky Guy); playwright and novelist Howard Waxman (Venceremos); and my colleagues in criticism, two-time Pulitzer Prize finalist and George Jean Nathan Award winner Michael Feingold (The Village Voice); David Sheward (ArtsinNY.com, Theaterlife.com and CulturalWeekly.com.); and Jerome Weeks (KERA, Dallas).

What follows is an edited version of our online conversation. Attempts to reach Mamet through his agent at ICM went unanswered.

Jeremy Gerard: So: Another free-speech beneficiary shuts down free speech and the exchange of ideas. I’ve had the experience of producers signing contracts with artists – playwrights, actors, directors – actually stating that reviews would not be “allowed.” And I’m used to playwrights attacking critics (Edward Albee, Davids Hare and Mamet perhaps most famously in recent decades), but I think this may be the first time one has tried to shut down audiences as well. How seriously should we take Mamet’s licensing demand? If I program a discussion about sexual harassment issues following my production of Oleanna, is that a violation of this clause? How about if I schedule a talkback on chocolate chip cookie recipes? One can support the Dramatists Guild’s hard-won rights over script control, but how can the Guild condone a member’s demand for control over what happens when the lights come up?

Gregory Mosher: Seeing plays is a largely subconscious experience. Analyzing them in an organized way can weaken or even kill what you just saw, so I think post-show discussions are best had in bars or restaurants, not from the stage. That said, this may not be the best tool in the writer’s kit.

Michael Feingold: I wish I knew what he was afraid of. I remember him when he wasn’t afraid of anything.

Peter Gerety: Michael, he’s never “not been afraid of anything,” he’s always been a bully.

Patrick Page: I don’t think he is afraid. He is trying to keep authority figures from explaining his work. Talk-backs are often led by dramaturgs or administrators who subtly guide the audience toward a particular understanding of the play and thus flatten the ambiguities and possibilities that an unguided discussion might ignite. I have frequently been infuriated as I participated in talk-backs where the person leading the discussion shut down ideas that did not correspond with her/his reading of the play. Better to let the work speak for itself.

‘The playwright has no more right to say what a theater does after a performance of his work than he has to tell the audience how to behave on the way home.’ – Village Voice critic Michael Feingold

‘The artist’s urge to protect his work from explanation and reduction is admirable.’ – Patrick Page, Actor

David Sheward: Watch the number of Mamet productions drop. You don’t think Mamet is overreacting just a tad?

Page: No. The “talk-back” is often a masturbatory attempt at building a subscription. Market driven. And I always participate. I am too narcissistic to resist. BTW, I despise Mamet’s politics and his theories on acting are risible. But the artist’s urge to protect his work from explanation and reduction is admirable.

Gerard: Patrick, your criticism of talk-backs as masturbatory suggests a problem in the execution, not the idea of them.

Jerome Weeks: Rather than some re-education camp, the talk-backs I’ve attended have generally been vague group-therapy sessions. The staff or actors almost always avoid giving their own sharp opinions unless it’s to praise the theater and/or the play in general (I’m so lucky to have this role). When theatergoers ask them direct questions (what did the playwright mean… ? did you like it when … ?), they’ve all seemed to be trained to turn the question back in their best sympathetic counselor voice: ‘Well, tell me what you think.’

Feingold: In my experience audiences at talk-backs are already subscribers, who regard the chance to exchange opinions with members of the production team as one of their perks. Most often they only want to say how much they enjoyed the work. I’ve sat in talk-backs as a dramaturg, an author, a translator, and a visiting scholar. And apart from the occasional crank with an ax to grind (like Shakespeare deniers), it’s mostly been vagueness and praise no matter what stimulating (or dogmatic) thoughts the dramaturg may toss out. Neither Mamet nor any other playwright has anything to fear from them, as far as I can tell. Anyway, it makes no sense to write a confrontational play and then attempt to suppress the confrontation.

Howard Waxman: He’s often a great writer and clearly a poseur much of the time, but he has no business shutting down discussion. He can dictate rules for how to do one of his plays but not about a discussion afterward.

Page: It is the guided discussion – inevitably led by someone who represents authority – that the playwright opposes. I understand. The play in question has a conservative viewpoint, for which we liberals should be thankful, as there are so few conservative artists. That viewpoint is unlikely to get a fair shake in any guided conversation at a LORT theater. Institutional theaters are frequently political as well as artistic organizations. They have an agenda involving color-blind casting, social justice, LGBTQ rights, feminism etc. I wholeheartedly agree with this agenda. But we mustn’t be blind to the fact that it is an agenda. The lack of truly conservative voices in the theatrical community is a loss. Mamet has written Oleanna about a teacher who is victimized by a militant student accusing him falsely of sexual harassment. Like it or not, that is the play’s content. A talk-back guided (inevitably) by a liberal administrator will likely spin the play and assert ambiguities the playwright did not intend. Also, I fervently support the rights of creators to have a say about the presentation of their work. That includes the whole event, not just what’s on the page.

Feingold: I think this misrepresents both the reality of the American theater and the reality of talk-backs, however “guided.” A theater that didn’t want Mamet’s viewpoint to be aired wouldn’t be doing a Mamet play in the first place. The assumption that unstructured discussion by individuals in small groups is automatically preferable to any form of organized discussion I find irrational as well as, probably, unconstitutional. The playwright has no more right to say what a theater does after a performance of his work than he has to tell the audience how to behave on the way home.

Page: I have never met a poet or a painter worth her salt who encouraged discussion of the artwork: it flattens ambiguities and leads to reduction. It is an institutional part of the modern theater that I think a Shakespeare or a Shaw would have been baffled by and find extraneous. I do think a playwright has such a right.

Feingold: But why should they have the right to stifle guided discussion? (You keep talking as if a moderator were some kind of manipulative criminal.) Production and casting are a different matter, as these deal with the actual body of the work, which is the playwright’s property.

Page: Whether or not the author has a “right” to limit discussion within a theater or a “right” to have a say over advertising, that is a legal question – maybe even a Constitutional one. My guess is the courts would decide that the creator has a right to whatever has been negotiated and agreed upon in her contract. I believe it takes courage, as a working artist, to take any position that goes against the prevailing winds of the community by which you hope to be employed. I know I think twice about voicing criticism of any potential employer.

Gerety: I did Oleanna at the Seattle Rep. We held talk-backs three or four times a week and the attendance was remarkable. What was also remarkable was the level of discourse from the audience … sometimes inspired and sometimes even personal reflection on the subject of entrapment, male privilege, university hierarchy, questioning of authority and all the other issues that the play alludes to. I always found those sessions to be exhilarating extensions of the play itself. It’s too bad David feels he has to take a cannon to dispense with something that is sometimes dull and, on the negative side, as threatening as a mouse.

Gerard: I’ve sat through many a talk-back and conducted a few myself. People have a hunger to be heard, exacerbated by social media that gives the illusion of an audience for all musing. Still, I’ve rarely left a talk-back that didn’t produce at least one lingering, unexpected insight. Yet I would no more require everyone to stay than prohibit the Q&A from taking place.

Doug Wright: As a playwright, I’m not wild about talk-backs; selfishly (perhaps) I’d rather that the writer have the last moment with the audience. How much more thrilling to end the evening on “And then I met James Tyrone, and was happy for a time,” or, “Willie, I made the last payment on the house today, and there’ll be nobody home. We’re free and clear. We’re free…” than the rambling pontifications of, say, a dentist from Greenpoint who wants to sound off about the show, or an effusive schoolteacher from Manhasset with a finite ability to self-censor. I’d much prefer audiences rest in the play for a while before they start trying to verbalize the experience, which – if done quickly – reduces it. However: I’ll never forget doing a talk-back at Playwrights Horizons after an early preview of I Am My Own Wife. A rather fetching man asked a question; I answered it, and he was apparently amused, because he began to “ask around” about me. Ultimately, we were set up on a blind date. We have now been together for 15 years! If I shared Mamet’s rather prohibitive point of view, I’d still be single! So there you have it.

Page: Doug, I couldn’t love this more.

Feingold: I second that emotion! I have to say I think Doug’s story is the definitive argument against Mamet’s notion. Love wins!

Gerard: What? I can’t hear you. There’s an army of dentists and schoolteachers hollering at me.

Related stories

David Mamet In Talks To Adapt Don Winslow NYPD Novel 'The Force' For James Mangold

David Mamet Teaches Master Class On Writing For Stage & Screen

Get more from Deadline.com: Follow us on Twitter, Facebook, Newsletter