Shaun Cassidy reflects on great lost new wave album ‘Wasp’ and why he walked away from music 40 years ago: ‘I didn't have any resentment’

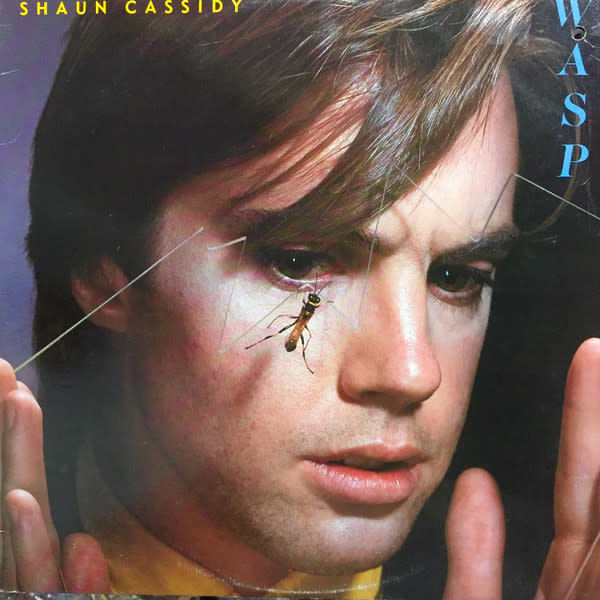

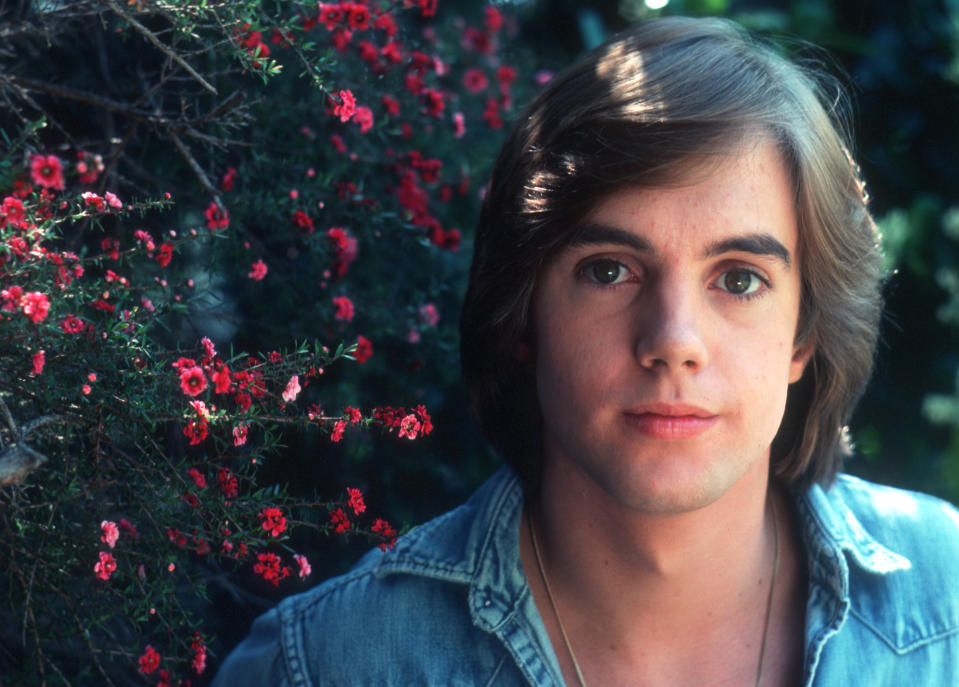

Forty years ago, on Sept. 1, 1980, teen idol Shaun Cassidy, the younger brother of late Partridge Family star David, released what turned out to be his final full-length studio LP, Wasp. To say that the new wave album was a departure from what both his record label and fanbase expected would be a massive understatement. Produced by the legendary Todd Rundgren, Wasp boasted a slew of hip cover tunes — David Bowie’s “Rebel Rebel,” Talking Heads’ “The Book I Read,” the Who’s “So Sad About Us,” the Animals’ “It's My Life,” Ian Hunter’s “Once Bitten, Twice Shy,” even the Four Tops’ “Shake Me, Wake Me” — as well as four fiery, feisty, funky originals written or co-written by Rundgren himself.

The ambitious album was actually a credible attempt by the younger Cassidy to leave his teenybopper past behind, but coming out exactly 11 months before the advent of MTV, it failed to register with fans, critics, or radio programmers at the time. To this day, sadly, it remains largely forgotten — even by Cassidy himself, who freely admits that he had to relisten to Wasp in its entirety, for the first time in decades, just to prepare for this epic interview reexamining its legacy.

As it turned out, Cassidy had no trouble reinventing himself after he left music and Wasp behind. After steadily working as an acclaimed theater actor in the ‘80s and ‘90s, he became a successful TV writer and producer for shows like American Gothic, Roar, Invasion, and most recently, New Amsterdam. However, in 2019, he did return to the concert stage after a 39-year hiatus, playing a Storytellers-style revue that featured the Wasp songs “So Sad About Us” and “Cool Fire” — because, he tells Yahoo Entertainment, “I felt I had a story to tell.”

“I created this sort of hybrid of a pop show and the theater show — and it ended up being really successful,” Cassidy says. “And when I do a show now, it's very emotional. The storytelling part of it is a survival story for me and for the fans, and Wasp is part of that. It's a unique story, because I don't know anybody, frankly, who had my [pop idol] experience and then just stopped and went away for 40 years, and then came back and said, ‘Anybody still here?’ And they are. The fans are still here. That feeling is there. It doesn't go away. And that's unique.”

Below, Cassidy reflects on the journey that led to Wasp, the journey he’s been on since, why his journey was so different from that of his troubled older brother, and why he has absolutely no regrets about walking away from pop stardom by the time he turned 22.

Yahoo Entertainment: Thank you so much for being willing to revisit Wasp, your final album, which came out 40 years ago!

Shaun Cassidy: Well, I'm grateful that you inspired me to listen to that record again, because it brought me back and made me think about a lot of stuff. Maybe there is something to talk about after all. I hadn’t listened to the whole thing in maybe 40 years. 1980 was such a transitional year for me, in so many ways. It was the last concert I did, until last summer. I played the Houston Astrodome for like 50,000 people and said goodnight, and I thought I'd probably do another concert in the next year or so. I didn't know Wasp would be the last record I'd make, but it was. And that year I did a short-lived TV series called Breaking Away, based on the movie. It was a critically lauded show that 12 people watched, and it was canceled.

So there I was — and I had recently gotten married too. I got married in December of ’79, at age 21. I was 21! I think about all that stuff happening to this 21-year-old kid, who I can be reasonably objective about now and have empathy for and some respect for. But what was fascinating to me — and I'll get into the specifics of making the Wasp record — was that I basically closed the door on all of that. I decided I wanted to be an actor in the theater, which is also telling about the record, because so much of Wasp is theatrical and sort of performance-driven — literally character-driven, with different voices on different songs. And that was the road I was on. For 10 years, all I did was work in theater, until I sold my first script in like ‘89 or ’90. And then I started writing television, and that's what I've been doing consistently, ever since.

I like that you used the term “transitional year,” because 1980 absolutely was that for pop culture. Disco was on the way out, and there were all these weird movie musicals, like Xanadu and Can't Stop the Music and The Apple, and new wave was coming in and MTV was right around the corner. It all seemed very accelerated. And Wasp captures a lot of that energy, I think.

You are basically saying everything I was going to say to you! For me specifically, my hit records, pop records, were kind of the last days of AM radio. Literally overnight, all my records stopped getting played. ... Every record of mine was dropped, and I wasn't being played on FM, which was still a relatively new animal and was more album-oriented anyway. So I had no airplay. I'd made these two wildly successful albums — the debut album, and then an album called Born Late — and then I came out with a record called Under Wraps, which was my favorite because I did the most writing on that one. But we didn't have a hit single on that album, so the handwriting was kind of on the wall. I wasn't a big fan of disco — I liked some records, like the early birth-of-disco records out of Philadelphia, but by the time 1979/1980 came around, it was all rehashing Saturday Night Fever. I was getting incredible pressure to try and make, if not a disco record, certainly a disco-infused record. Which I balked at.

So you decided to go new wave instead?

Well, in this scenario, you either decide you are going to commit to a career as an artist, and with any luck to work your way into the Justin Timberlake territory, or you move on. Or you go the third road, which was what I did, which was: “I'm going to call one of my heroes, Todd Rundgren!”

What inspired you to call Todd?

Something/Anything? was a seminal record for me. “Couldn’t I Just Tell You” is arguably one of the first great powerpop songs. And I had aspired to make powerpop records. … I knew that Todd had produced a lot of eclectic acts. I'd loved the New York Dolls’ debut album. He’d made some really good records for Grand Funk and the Tubes. He was all over the map, and he struck me as kind of like Dave Eggers as a writer. He was doing cool new things and being deconstructionist and ironic about all of it, all at the same time. I wanted to be pushed, and I wanted to be inspired. And so I told the record company, “I want to make a record with Todd and see if he's game.” We had a great meeting at my house and Todd said, “Yeah, sure. Let's do it.”

How did you end up going in this very new musical direction, once you started working together?

I didn't know what the album would be. I said, “Will I be writing all the songs? Because I've been writing a lot more.” He said, “No, no, no, no, no, you don't have to do that. You don't have any super-legacy as a songwriter to uphold. You want to be an actor. Let's make a record that leans into that, pushes you into characters.” Some of the record I think is really good. Some of it I think is goofy. Some of the tracks, I think, overextend — I don't think anyone should be [covering] David Byrne! But again, 40 years after the fact, looking back at this 21-year-old kid, I'm impressed with the scope of it. I'm impressed with the commitment I hear in it. I don't remotely regret making that record. I'm glad I did.

What was the reaction from your record company? This was hardly the commercial product they were used to.

I remember we had a listening party at Warner Bros., and Russ Thyret, a very famous promotion man who later ended up running Warner Bros., said, “Um, well, it's interesting. I don't know what your fans are going to say and I don't know what radio is going to think, but I certainly think the best single to go with is ‘So Sad About Us’” — which was an old Who song that we recorded. I said, “Yeah, but that's so poppy; it sounds like my other records except maybe a little harder and edgier. I don't want to do that. Let's do ‘Rebel Rebel.’” I was a huge Bowie fan and I listened to “Rebel Rebel” when it first came out, on like English transplant records that you couldn't even get in America. So I basically forced Warner into going with “Rebel Rebel” [as the lead single]. And maybe that was a horrible idea, because nobody played it. “So Sad About Us” actually might have been a better transition from my previous records.

So Wasp obviously was a commercial flop…

Yeah. When the record sold, like, eight copies, my contract was coming up at Warner Bros. and I went in to have this meeting with Russ. I said, “So, what do I do?” He said, “You need to go away for a while. You can always come back, but you need to go away and let people miss you, and then come back.” So I went away for 40 years! I realized really quickly that I didn't want to come back. I wanted to go forward. Because I knew I had a different story to tell. The story that had been laid out for me as a kid was because there'd been a prototype in David already. You know, I'd been in a punk band. I was playing all these bars on Sunset when I was 15 or 16 years old and hanging out with Iggy Pop and the New York Dolls.

Really?

Yes, there’s a photo of this, in all its glory, in the book Please Kill Me. I had no business being in any of those places at my age, and I lived to tell the tale — and I am grateful for that. But by the time [Warner] signed me, they didn't sign my band. They signed me. They cleaned me up and said, “You're going to make pop records.” And I kind of dutifully went along. I liked some of my early records and I will happily play some of them, but most of them didn't challenge me all that much. And you know, I actually could sing. I had a pretty big baritone voice, which wasn't really the fashion of the day. But if you put on a Jim Morrison record or a David Bowie record or an Eric Burdon record, I could sing it in the key with some conviction.

So, overall, was the sound of Wasp — more punk, more glam — the sort of music you’d wanted to do all along?

That was the stuff that was fueling what I wanted to do, but I didn't look like that. And I didn't come from that. Like I said, there was a successful precedent beforehand with David. And when I ended up on television [on The Hardy Boys Mysteries], literally there was a formula already, ready to go. They knew exactly how to do it, and they did it really successfully. I didn't have any resentment about it. I sort of went on the ride and thought, “Oh, this is interesting. This is winning a lottery of sorts.” I just went the path of least resistance. I was so young and I was just looking around going, “Who knows better than me? Oh… everyone!” So I listened. But anyway, because I wasn't really invested in it personally, it didn't hurt me either. When it was all over, it was like, “OK, that was interesting. Now what?”

But I imagine that when you got this opportunity to do an edgier-sounding album with Todd Rundgren, you must've felt like a kid in a candy store for a while.

One hundred percent! … But I kind of did the same thing with Todd on Wasp: I handed the reins completely to him and I said, “What do we do here?” It freed me up to do everything, and it gave me license to be good and license to be bad. And I think the record reflects that. … It was the joy of trying something new and pushing myself and testing myself, and being more excited than worried about outcome. I wasn't really ever that invested in outcome. I just wanted to have the experience and the process. And I still do.

I'm fascinated by the whole idea of this album being character-driven. What are some of the tracks that you think really illustrate that?

Definitely “Cool Fire.” If I ever go on the road again, I'll play it again. I love it because it's about television. I mean, it's a Marshall McLuhan phrase. It's a bit of biting the hand that has fed me for a long time, because it's about my mixed feelings about television. Todd wrote the lyrics — I didn't, but we had talked about that subject — and I came in with a melody. That's the only song I contributed to writing on the record. We all wrote it together: [Utopia’s] Kasim [Sulton] and Roger [Powell] and Willie [Wilcox]. Those guys were great too, by the way. It was fun to be kind of in a band. I wasn't really in the band, but they made me feel welcome. I'm really fortunate to have worked with them

I’m a fan of Wasp’s title track. I think it’s a monster. Vocally, you really go off and have so much attitude. It's almost like a Mick Jagger/“Shattered”-style attitude. I have always wondered if you improvised that.

I did, kind of, actually! It was so different from anything I'd ever done or been given the opportunity to do. I said, “Just let me go for it!” And I did.

You seemed to be pushing yourself a lot vocally on this record. Were you happy with the results?

Some of it. “Once Bitten, Twice Shy” was a song I’d wanted to actually record earlier. So I suggested that, and I suggested doing it in the low register. I remember saying to Todd, “How high should the key be?” He said, “It should be as high as you can sing it in — and then up a step!” And that is what we did with every one of these songs. I can hear my voice cracking on some of them; I'm really screaming on a lot of them.

“The Book I Read,” I love the song, but when I listen to it, I hear me aping David Byrne, which is never a good idea — as opposed to “Once Bitten, Twice Shy” or “Rebel Rebel,” where I'm not [mimicking] Ian Hunter or Bowie. I love “Pretending,” one of the originals that Todd wrote; it feels theatrical, like it could be in a Broadway musical. “Shake Me, Wake Me” is fun because it's sort of Motown, and yes, I did listen to Levi Stubbs a little bit before I did that — not that I could ever approach Levi Stubbs, who might be one of the best vocalists ever. I think “Selfless Love” is my least favorite track because it feels very self-important. It's about suicide, and I wasn't feeling as dark as that song is.

I think if I had on dollop of fairy-dust to add to the record, I would put more joy in it. Elvis Costello is one of my favorite artists, and he was sort of breaking around the same time. He would write these incredible powerpop melodies that sounded like the most upbeat songs in the world, and then you'd listen and the lyrics were so dark. The juxtaposition of the darkness and light was what made it so interesting. I wish there was just a little bit more of that in Wasp. But that's just me now. What did I know at 21?

Do you ever wonder, if you hadn’t walked away from music at 21, if the Wasp sound is the path you would have stayed on musically?

Well, I have a weird résumé. I just do. I had this incredibly big, explosive opening number in my early career. Then I literally stayed at home for the ‘80s, except for doing tiny little theaters, doing weird, like, Joyce Carol Oates plays for $100 a week. And then I wrote a pilot called American Gothic that ended up being kind of a big deal and paved the way for me to create a lot of other television shows and write and produce a lot of television. I'm an executive producer on a show called New Amsterdam now, which I think is a really good show and I’m grateful to be there. But this [musical] part of my life was not very long — like, I probably played Little League baseball for as long as I recorded! And yet, I am known for this time because it was a big deal in the day to a certain a group of people. For me, it's just a brick in the wall. But the Wasp record is so unique compared to the others, and there's stuff on there that portends of, “Oh, you could have done something else...” And I did get to do some other stuff in the theater that, I guess, was similar in some ways.

We’ve established that Wasp wasn't exactly flying off record store shelves, but was it critically praised at the time?

It got really great reviews. And some horrific reviews! There was no consensus. I think certainly in any critical review it was like, “Well, what's he trying to do here?” The sense that there was an “agenda” to it, I think, clouded any objectivity about it. Subsequently, a lot of people, like you, have come up to me and said, “Hey, I really loved that record. What happened? Where did that come from?” These are people that I guess collect offbeat stuff, discover stuff, and can look at it with fresh eyes, without all the context of “he's trying to reinvent himself” — which I really wasn't.

But as you mentioned, you obviously ended up reinventing yourself professionally later — several times.

When I look back — and I don't look back often — I think I'm most proud of this kid who could have been sidelined by so many things. There are so many cases of people who've had a similar experience who didn't survive it. I'm grateful that I did. I don't know how I did. I don't know why I did. But I have the life that I hoped I'd find. I'm really the luckiest man. That whole experience of my early youth, I embrace it and I have no issue with it. I had a great time doing it. I learned a lot doing it. I carry some of it with me still. I'm happy to have had the arc with the records I had, and it comes out in different ways and other things later.

Do you have any idea how you avoided the tragedies that other ‘70s teen idols suffered? I think of Leif Garrett, or Andy Gibb…

Or my brother, David. Yeah. To put David in context, David had a very good career for a long time — but he was always pushing back on his early success. He had felt exploited and he didn't enjoy it. And I did enjoy it. But also I wasn't invested in it. I'm a writer. I wrote a song about this called “Teen Dream,” which people think was about me, but it's actually about the audience. It's about this sort of collective hormonal hysteria that happens when you get together with your friends. I'd seen what happened with the Beatles, and with David, and so then when it happened to me, I was like, “Oh, I'm in the middle of this hurricane. That isn't about me. I can ride this out. And then I'll see what I do for a living afterwards.”

Read more from Yahoo Entertainment:

Nigel Lythgoe on his disco cult movie, ‘The Apple’: ‘The best part of making it was finishing it’

The Tubes’ Fee Waybill recalls bonkers 'Xanadu' scene: 'What, are you a disco band now?'

Remembering when Aerosmith kicked ass in 'Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band'

Debbie Allen recalls the grittiness of ‘Fame,’ 40 years later: ‘It was not a Disney movie’

The lost David Cassidy interview: 'Call me bad, call me lousy, but don't call me a former teen idol'

Follow Lyndsey on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Amazon and Spotify