Sex in Cinema: The Hays Code, Censorship, and Film’s First Culture War

The post Sex in Cinema: The Hays Code, Censorship, and Film’s First Culture War appeared first on Consequence.

Welcome to Sex in Cinema Week, Consequence‘s deep dive into movies, the Hays Code, and what society labels taboo. Check back throughout the week for essays, interviews, and lists examining censorship of movie sex scenes and the creativity it inspired in filmmakers.

American cinema can be divided into three eras of censorship, and William H. Hays played a part in all of them. The first era, wild and sexy, stirred a backlash to young Hollywood that allowed Hays to leave his political career and consolidate power in film. The second, from 1934 to 1968, saw the industry policed by the Motion Picture Production Code, colloquially known as the Hays Code. During the third period Hays’ ideas evolved into the MPAA rating system, when his influence could be felt in almost every undeserved R and bizarre NC-17.

In retrospect, his rise to power in the movie industry feels unlikely, though that may be because all of 1920s Hollywood is almost beyond belief. If Thomas Edison hadn’t pursued a vicious monopoly on film patents from his home base in New Jersey, he might not have pushed aspiring filmmakers to the opposite end of the country, where long train rides sapped the power of his hired thugs and wildcat judges laughed his lawsuits out of court. And if the film industry had instead grown up amid the old money and entrenched values of the East Coast, then the early movies might have looked very different, and the world outside Hollywood might not have been quite so scandalized at what they saw.

Cecil B. DeMille’s The Sign of the Cross (Paramount Pictures)

And sex is what they saw. Usually not explicitly, though some people filmed sexual documentaries as well as wink-wink “documentaries.” But many early silent films pulsed with the idea of fucking: sly innuendos, suggestive costumes, lusty character arcs, and more. Just as bad in the eyes of conservative critics, some movies voiced young Hollywood’s radical politics, challenging traditional ideas of masculinity and femininity with independent flapper women, gay-coded characters, drag performers, and more. A few filmmakers offered at-the-time progressive ideas on race, and like many vibrant artistic scenes around the world in the 1920s, Hollywood was full of socialists.

Plus, the film industry came of age alongside national and international media organizations. Other famed art scenes — the impressionist painters of Paris, the poets of London, the playwrights of Ancient Athens — surely threw wild parties, but they did so without the whole world knowing about it. The young stars of Hollywood had no such luck. At the height of Prohibition, breathless newspaper reports carried wild tales not just of drinking, but “dope parties” where revelers partook of the devil’s lettuce.

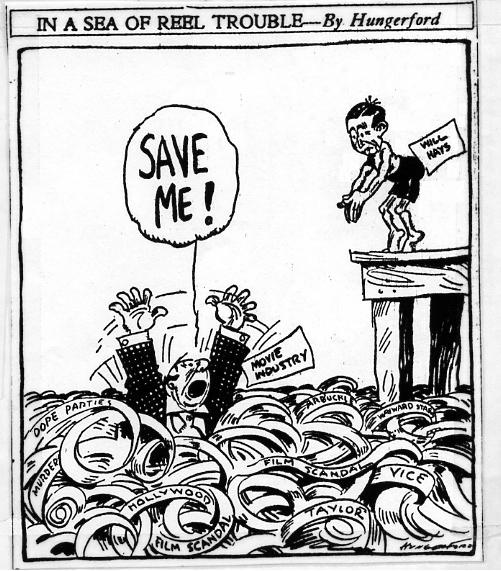

The media fascination with Hollywood reached new heights of frenzy in 1921 and 1922 with two high-profile investigations: the death and alleged rape of Virginia Rappe at the hands of Fatty Arbuckle (later acquitted), and the unsolved killing of director William Desmond Taylor. These scandals damaged the film industry. In Robert Giroux’s A Deed of Death: The Story Behind the Unsolved Murder of Hollywood Director William Desmond Taylor, one Los Angeles official surveyed the aftermath: “The industry has been hurt. Stars have been ruined. Stockholders have lost millions of dollars. A lot of people are out of jobs.” And in the midst of crisis, Will Hays was meant to be a savior.

Cartoon by Cy Hungerford, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, 1922

In 1922, Hays became the first head of a brand-new trade association, the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America (MPPDA), later the MPAA, now the MPA, and often pronounced FU. At the time of his hiring, the MPPDA touted his rock-solid conservative credentials, because church leaders and right-leaning politicians were calling for an end to what they saw as evil behavior, pressuring state censorship boards to block films. In networking together, conservatives not only marshaled their forces for the first film culture war, but laid the infrastructure for every culture war to follow. Hollywood came under enormous pressure, and the monied interests sought out someone unimpeachable.

As it turned out, Hays’ sterling reputation in 1922 was another accident of timing. A Protestant church deacon and the onetime chair of the Republican party, Hays led the election campaign of President Warren Harding, in the process playing a small part in the Teapot Dome bribes that would remain the worst US political scandal until Watergate. Luckily for him, before his role in the scandal became public, he left Harding’s cabinet to join the MPPDA and help them “clean up the pictures.”

Hays began by communicating with local censorship boards to lobby for leniency, but he soon came around to a strategy of “self-censorship.” The MPPDA advised studios to voluntarily moderate their content in order to appeal to the broadest possible audience.

In 1927, Hays led the MPPDA in codifying the “Don’ts” and “Be Carefuls,” and many of these ideas would get more formal support in the 1930 Motion Picture Production Code. Religious leaders also played a part. The code included input from a Jesuit priest and a Catholic writer, and to enforce those standards, Hays hired as chief censor the prominent Catholic influencer Joseph Breen. A church official himself, Hays built a self-consciously religious institution. In a little over a decade, that nascent conservative network had succeeded in creating a check on Hollywood.

Among other warnings, Hays pushed filmmakers to avoid discussions or suggestions of sex, showing men and women in bed together, miscegenation (socializing or romance between people considered to be different races), and “any inference of sex perversion,” which was understood to include all deviations from heterosexuality. Betty Boop had to put on more clothes. Lust was to be measured with a stopwatch; according to the code, a kiss became obscene if it lasted longer than three seconds.

In 1934, with broad support from Hollywood’s financiers (though not its talent), the MPPDA began to vigorously enforce what was increasingly called the Hays Code. In the span of a few short years, the film industry underwent a transition almost as violent as silent to sound. But whereas sound added something new, the Hays Code was instead an amputation. Many kinds of people and stories nearly disappeared from American cinema.

I say nearly, because the changes also fomented rebellion. Filmmakers like Alfred Hitchcock studied the code with a lawyer’s eye and a vandal’s intentions. Sensuality found new expressions, and directors developed rich visual vocabularies to sneak eroticism past the censors.

Alfred Hitchcock’s Notorious (RKO Radio Pictures)

Hays left the organization in 1945, the same year the MPPDA rebranded to MPAA (Motion Picture Association of America). The code was made even stricter in the 1950s but was all the while growing more unpopular, and during the cultural revolution of the 1960s it became untenable. Almost 55 years ago exactly, in November of 1968, the Motion Picture Production Code was finally undone, replaced with an MPAA rating system that allowed adults to finally access more mature content.

But a softer censorship remained, and many of the same communities that had been shut out of the film industry during the Hays Code found themselves disadvantaged by MPAA’s new R ratings. As was revealed in the 2006 documentary This Film Is Not Yet Rated, the organization employed members of the clergy. More than 100 years after Hays began, the group he built continues to provide a religious check on liberal Hollywood.

Altogether, American cinema has been defined by three wildly different approaches to censorship: before Hays, during Hays, and the next evolution of his system. Consequence is taking a deeper dive into each of these eras during Sex in Cinema Week, and you can read more about them as we break down how filmmakers reacted to each era of censorship, from the pre-Code days to the MPAA era. We’ll also be going behind the scenes with the intimacy coordinators of today, who make sure that today’s sexual content in films is better — and safer — than it has been in years, and wrapping things up by paying tribute to the sexiest scenes to ever make it to the big screen.

Sex is not just the backstory we all share, it’s been at the forefront of every battle over the freedom of American cinema. Fifty-five years after the end of the Hays Code, we can see how a few accidents shaped film history. It’s not hard to imagine a world where Hays never headed the MPPDA. But the story is also one of broad cultural conflicts — of forces much bigger than any one person. If not Hays, it would have been someone else. If not then, earlier or later. Two Americas were on a collision course, and the movies were destined to be a battlefield.

Sex in Cinema: The Hays Code, Censorship, and Film’s First Culture War

Wren Graves

Popular Posts