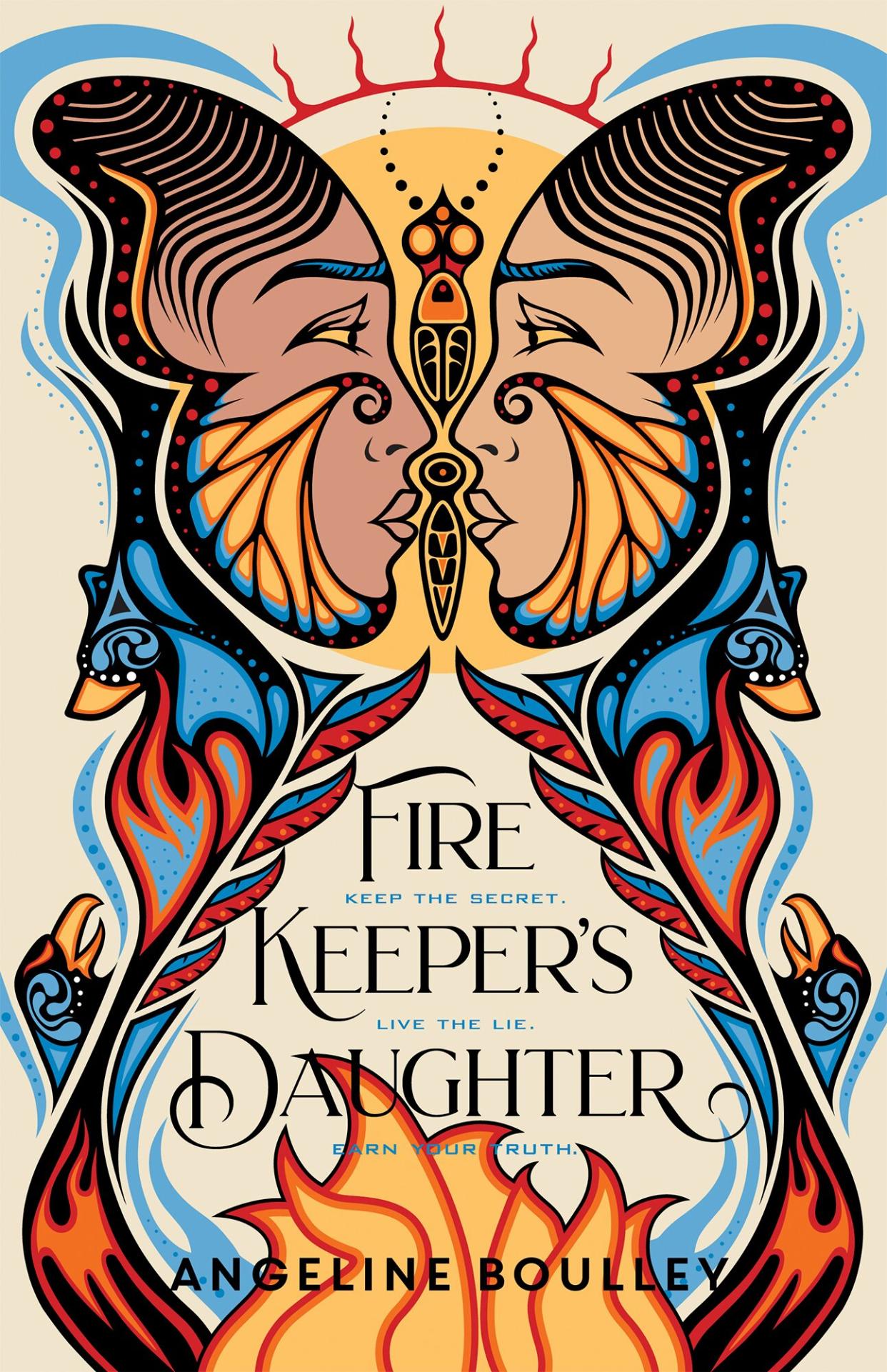

See a first look at Firekeeper's Daughter , a groundbreaking new YA thriller

6149422217001

What do you get when you combine Tommy Orange, Angie Thomas, and Tomi Adeyemi? This genre-bending new YA thriller. Firekeeper's Daughter is a debut by Angeline Boulley, who spent 10 years crafting the story about corruption that threatens her Ojibwe community — the author herself is an enrolled member of the Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians — and sold the project in a whopping 12-way auction. The tome is on sale March 2, 2021 (you can preorder it now), and EW has your first look at the prologue and first chapter. Below, the official synopsis:

As a biracial, unenrolled tribal member and the product of a scandal, eighteen-year-old Daunis Fontaine has never quite fit in, both in her hometown and on the nearby Ojibwe reservation. Daunis dreams of studying medicine, but when her family is struck by tragedy, she puts her future on hold to care for her fragile mother.

The only bright spot is meeting Jamie, the charming new recruit on her brother Levi’s hockey team. Yet even as Daunis falls for Jamie, certain details don’t add up and she senses the dashing hockey star is hiding something. Everything comes to light when Daunis witnesses a shocking murder, thrusting her into the heart of a criminal investigation.

Reluctantly, Daunis agrees to go undercover, but secretly pursues her own investigation, tracking down the criminals with her knowledge of chemistry and Ojibwe traditional medicine. But the deceptions—and deaths—keep piling up and soon the threat strikes too close to home.

Now, Daunis must learn what it means to be a strong Anishinaabe kwe (Ojibwe woman) and how far she'll go to protect her community, even if it tears apart the only world she’s ever known.

Boulley (virtually) stopped by the famed Birchbark Books (owned, of course, by one Louise Erdrich) in Minneapolis last night to talk about her years spent crafting the thriller, and to debut the book's cover (seen above, with Art by Moses Lunham and Rich Deas and design by Rich Deas). Watch her conversation with author Carole Lindstrom, and read an exclusive excerpt below.

Henry Holt Books for Young Readers

Prologue

I am a frozen statue of a girl on my knees in the woods. Only my eyes move, darting from the gun to their startled expression.

Gun. Shock. Gun. Disbelief. Gun. Fear.

THA-THUM-THA-THUM-THA-THUM.

The snub-nose revolver shakes with tiny tremors from the jittery hand aiming at my face.

I’m gonna die.

My nose twitches at a greasy sweetness. Familiar. Vanilla and mineral oil. WD-40. Someone used it to clean the gun. More scents: pine, damp moss, skunky sweat, and cat pee.

THA-THUM-THA-THUM-THA-THUM.

The jittery hand makes a hacking motion with the gun, as if wielding a machete instead. Each diagonal slice towards the ground gives me hope. Better a random target than me.

But then terror grips my heart again. The gun. Back at my face.

Mom. She won’t survive my death. One bullet will kill us both.

A brave hand reaches for the gun. Fingers outstretched. Demanding. Give it. Now.

THA-THUM-THA-

I am thinking of my mother when the blast changes everything.

In Ojibwe teachings, all journeys begin in the eastern direction.

Part 1: Waabinong (East)

Chapter 1

I start my day before sunrise, throwing on running clothes and laying a pinch of semaa at the eastern base of a tree, where sunlight will touch the tobacco first. Prayers begin with offering semaa and sharing my Spirit name, Clan, and where I am from. I always add an extra name to make sure Creator knows who I am. A name that connects me to my father—because I began as a secret and then, a scandal.

I give thanks to Creator and ask for Zoongidewin, because I’ll need courage for what I have to do after my five-mile run. I’ve put it off for a week.

The sky lightens as I stretch in the driveway. My brother complains about my lengthy warm-up routine whenever he runs with me. I keep telling Levi that my longer, bigger, and therefore vastly superior muscles require more intensive preparation for peak performance. The real reason, which he would think is dorky, is that I recite the correct anatomical name for the muscles as I stretch. Not just the superficial muscles but the deep ones, too. I want an edge over the other college freshmen in my Human Anatomy class this fall.

By the time I finish my warm-up and anatomy review, the sun peeks through the trees. One ray of light shines on my semaa offering. Niishin! It is good.

My first mile is always hardest. Part of me still wants to be in bed with my cat, whose purrs are the opposite of an alarm clock. But if I power through, my breathing will find its rhythm, accompanied by the swish of my heavy ponytail. My legs and arms will operate on autopilot. That’s when my mind will wander into the Zone, where I’m part of this world but also somewhere else, and the miles pass in a semi-alert haze.

My route takes me through campus. The prettiest view in Sault Sainte Marie, Michigan is on the other side. I blow a kiss as I run past Lake State’s newest dorm, Fontaine Hall, named after my grandfather on my mother’s side. My grandmother Mary—I call her GrandMary—insisted I wear a dress to the dedication ceremony last summer. I was tempted to scowl in the photos but knew my defiance would hurt Mom more than it would tick off GrandMary.

I cut through the parking lot behind the student union toward the north end of campus. The bluff showcases a gorgeous panoramic view of the St. Mary’s River, the International Bridge into Canada, and the city of Sault Sainte Marie, Ontario. Nestled in the bend of the river east of town is my favorite place in the universe: Sugar Island.

The rising sun hides behind a low, dark cloud at the horizon beyond the island. I halt in place, awestruck. Shafts of light fan out from the cloud, as if Sugar Island is the source of the sun’s rays. A cool breeze ruffles my t-shirt, giving me goose bumps in mid-August.

“Ziisabaaka minising,” I whisper in Anishinaabemowin the name for the island, which my father taught me when I was little. It sounds like a prayer. My father’s family, the Firekeeper side, is as much a part of Sugar Island as its spring-fed streams and sugar maple trees.

When the cloud moves on and the sun reclaims her rays, a gust of wind propels me forward. Back to my run and to the task ahead.

###

Forty-five minutes later, I end my run at EverCare, a long-term care facility a few blocks from home. Today’s run felt backwards, peaking in the first mile and becoming progressively more difficult. I’d tried chasing the Zone, but it was a mirage just beyond my reach.

“Mornin’, Daunis,” Mrs. Bonasera, the head nurse says from behind the front desk. “Mary’s having a good day. Your mom’s already here.”

Still catching my breath, I give my usual good morning wave.

The hallway seems to lengthen with each step. I steel myself for possible responses to my announcement. In my imagined scenarios, a single furrowed brow conveys disappointment, annoyance, and the retracting of previous accolades.

Maybe I should wait until tomorrow to announce my decision.

I pause to twist my upper body until I hear a satisfying crack. If I wait until I’m in GrandMary’s room, Mom makes the sign of the cross whenever I do this.

Mrs. B. didn’t need to say anything; the heavy scent of roses in the hallway announces Mom’s presence. When I enter the private room, she’s gently massaging rose-scented lotion on my grandmother’s thin arms. A fresh bouquet of yellow roses adds to the floral saturation level.

GrandMary’s been at EverCare for six weeks now and, the month before that, in the hospital. She had a stroke at my high school graduation party. Visiting every morning is part of the New Normal, which is what I call what happens when your universe is shaken so badly you can never regain the same axis as before. But you try anyway.

My grandmother’s eyes connect with mine. Her left brow raises in recognition. Her right side is unable to convey anything.

“Bon matin, GrandMary.” I kiss both cheeks before stepping back for her inspection.

In the Before, her scrutiny of my fashion choices bugged the crap out of me. But now? Her one-sided scowl at my oversized t-shirt feels like a perfect slap shot to the top shelf.

“See?” I playfully lift my hem to reveal yellow Spandex shorts. “Not half-naked.”

Halfway through her barely perceptible eye roll, GrandMary’s gaze turns vacant. It’s like a light bulb behind her eyes that someone switches on and off arbitrarily.

“Give her a moment,” Mom says, continuing to smooth lotion onto GrandMary’s arms.

I nod and take in GrandMary’s room. The large picture window with a view of a nearby playground. The dry erase board with the heading, Hello! My name is Mary Fontaine, and a line for someone to fill in after My Nurse. The line after My Goals is blank. The vase of roses surrounded by framed photographs. GrandMary and Grandpa Lorenzo on their wedding day. Mom and Uncle David in matching white First Communion outfits. My senior picture fills a silver frame engraved with Class of 2004.

The last picture taken of the four of us Fontaines—me, Mom, Uncle David, and GrandMary—at my final hockey game brings a walnut-sized lump to my throat. I went to sleep many nights listening to Mom and her brother laughing, playing cards, and talking in the language they had invented as children—a hybrid of French, Italian, abbreviated English, and made-up nonsensical words. But that was before Uncle David died last April and GrandMary, grief-stricken, had an intracerebral hemorrhagic stroke two months later.

Who will make my mother laugh in the New Normal now that Uncle David is gone?

My mother looks up and gives me a tired smile. She didn’t sleep again last night, instead cleaning the house in a frenzy while talking to Uncle as if he was sitting on the sofa watching her dust and mop. I wake up during those darkest hours, when she confesses her loneliness and regrets to him, unaware that I am fluent in their secret language.

While I wait for GrandMary to return to herself, I retrieve a lipstick from the basket on the bedside table. GrandMary believes in greeting the day with a perfect red smile. Gliding the matte ruby over her thin lips, I remember my earlier plea for courage. To know Zoongidewin is to face your fears with a strong heart. My hand twitches; the golden tube of lipstick a jiggling needle on a seismograph.

Mom finishes with the lotion and kisses GrandMary’s forehead. I’ve been on the receiving end of those kisses so often that an echo of one warms my own forehead. I hope GrandMary can feel that good medicine even when the light bulb is off.

When my grandmother was in the hospital, I kept track of how many times she blinked during the same fifteen-minute window each day. Mom didn’t mind my record-keeping until she noticed the separate tally marks for Light bulb On and Light bulb Off. The overall number of blinks hadn’t changed, but the percentage of alert ones (Light bulb On divided by Total Blinks) had begun to decrease. My mother got so upset when she saw my tally that now I keep the blink notebook hidden in the closet now, bringing it out only on mornings when Mom isn’t here so early.

It happens. GrandMary blinks and her eyes brighten. Light bulb On. Just like that, her focus sharpens, and she is once again a mighty force of nature, the Fontaine matriarch.

“GrandMary,” I say quickly. “I’m deferring my admission to U of M and registering for classes at Lake State. Just for freshman year.” I hold my breath, anticipating her disappointment in my deviation from The Plan: Daunis Lorenza Fontaine, M.D.

At first, I’d gone along with it hoping to make her proud. I grew up overhearing people whisper with a sort of vicious glee about The Big Scandal of Mary and Lorenzo Fontaine’s Perfect Life. I pretended so well and for so long, that her plan became my plan. Our plan. I loved that plan. But that was Before.

GrandMary fixes me with a gaze as tender as my mother’s kisses. Something passes between my grandmother and me. She understands why I had to alter our plan.

My nose tingles with pre-cry pinpricks from relief, sadness, or both. Maybe there’s a word in Anishinaabemowin for when you find solid footing in the rubble after a tragedy.

Mom rushes around the bed, pulling me into an embrace that whooshes the air from my lungs. Her joyful sobs vibrate through me. I made my mother happy. I knew I would, but I didn’t expect to feel such relief myself. She had been pushing for me not to go away to college, even encouraging Levi to pester me about it. Mom had pleaded with me to fill out the Lake State admissions form last January as a birthday gift to her. I agreed, thinking there was no way anything would come to pass. Turns out, there was a way.

A bird thuds against the window. My mother startles, releasing me from her grip. I only get three steps towards the window when the bird rises, fluttering to regain equilibrium before resuming its journey.

Gramma Pearl—my Anishinaabe Nokomis on my Firekeeper side—considered a bird flying into a window as a bad sign. She would rush outside with a leathered brown hand at her mouth, muttering uh uh oh at its crooked neck before calling her sisters to figure out which tragedy was just around the corner.

But GrandMary would say it was random and unfortunate. Nothing more than an unintended consequence of a clean window. Indian superstitions are not facts, Daunis.

My Zhaaganaash and Anishinaabe grandmothers could not have been more different. One viewed the world as its surface while the other saw connections and teachings that ran deeper than our known world. Their push and pull on me was a tug-of-war my entire life.

When I was seven, I spent a weekend at Gramma Pearl’s tarpaper house on Sugar Island. I woke up crying with an earache, but the ferry to the mainland had shut down for the night. So she had me pee in a cup, and poured it into my ear as I rested my head in her lap. Back home for Sunday dinner at GrandMary and Grandpa Lorenzo’s, I excitedly shared how smart my other grandmother was. Gramma Pearl fixed my earache with my pee! GrandMary recoiled and, a heartbeat later, glared at my mother as if this was her fault. Something split inside me when I saw my mother’s embarrassment. I learned there were times when I was expected to be a Fontaine and other times when it was safe to be a Firekeeper.

Mom returns to GrandMary, moving the cashmere blanket aside to massage lotion on a spindly leg. She’s exhausting herself looking after my grandmother. Mom is convinced she will recover. My mother has never been good at accepting unpleasant truths.

A week ago, I woke up during one of Mom’s cleaning frenzies.

I’ve lost so much, David. And now her. When Daunis leaves, j’disparaître.

She had used the French word for disappear. To fade or pass away.

Eighteen years ago, my arrival changed my mother’s world. Ruined the life her parents had preordained for her. I am all she has left in this world.

Gramma Pearl always told me, Bad things happen in threes.

Uncle David died in April.

GrandMary had a stroke in June.

If I stay home, I can stop the third bad thing from happening. Even if it means waiting a little longer to follow the Plan.

“I should go.” I kiss Mom and then GrandMary goodbye. As soon as I leave the facility, I break into a run. I usually walk the few blocks home as a cool-down, but today, I sprint until I reach my driveway. Gasping, I collapsing beneath my prayer tree. Waiting for my breath to return.

Waiting for the normal part of the New Normal to begin.

Related content: