The Secret Service Agent Who Jailed the KKK and Paved the Way to Guantanamo

On the night of September 2, 1871, several members of the Ku Klux Klan locked up Henry Lowther, a black farmer from Georgia whom they accused of plotting an armed uprising of black men and sleeping with white women. Two nights later, 180 Klansmen took Lowther from his cell, tied him up, and led him to a swamp, where they threatened to lynch or castrate him.

They chose the latter.

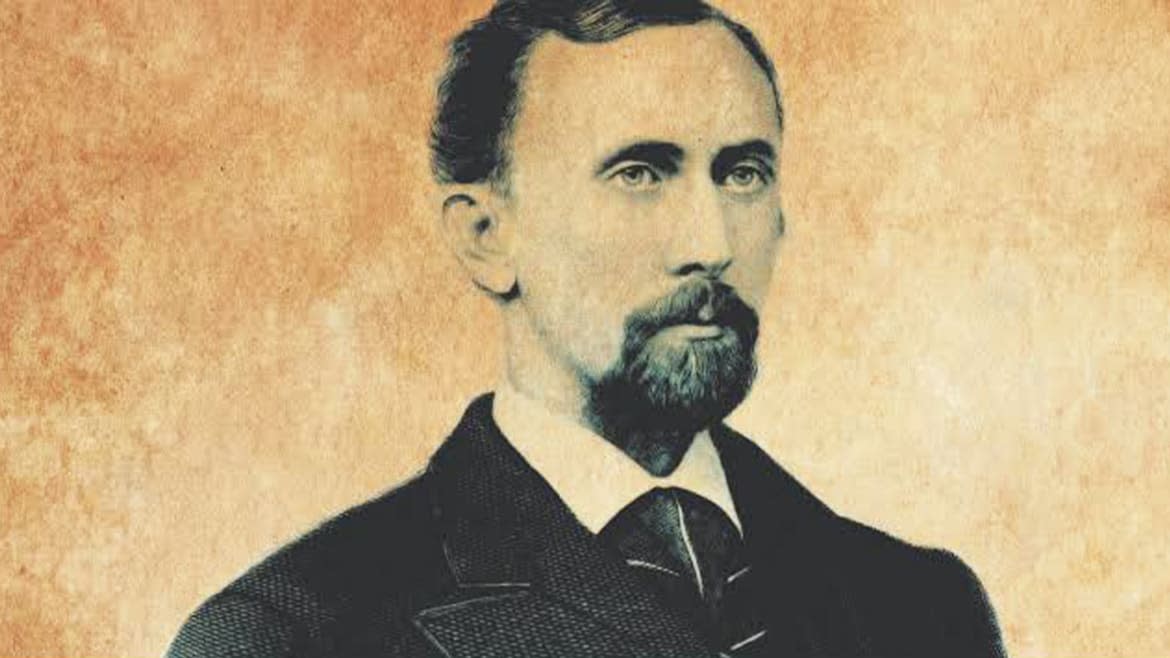

Atrocities like these were not uncommon in the South after the Civil War, which was why the United States Secret Service set up a clandestine unit to infiltrate and destroy the Klan. In Freedom’s Detective: The Secret Service, The Ku Klux Klan and the Man Who Masterminded America’s First War On Terror, author Charles Lane tells how Hiram C. Whitley, then head of the Secret Service, ran this anti-terrorist operation, and how some of his methodology continues to influence today’s war on groups like Isis and Al Qaeda.

“Whitley has been completely lost to history,” said Lane in an interview with The Daily Beast. “He does not get the credit he deserves for innovative tactics fighting this unprecedented evil in the country.”

Whitley was not the most obvious choice to run a program tasked with protecting the black citizens of the South and their white supporters. A former slave-catcher and ethically slippery businessman—Lane says in the book that “throughout his life, Hiram C. Whitley practiced situational honesty”—Whitley initially entered the spy business when he offered his services to the Union Army as a source of intelligence on rebel-held areas north of New Orleans.

After the war, and after a period of time living in Massachusetts, where he was accused of swindling an apothecary out of his shop and selling fake whiskey and diamonds (he somehow managed to avoid criminal liability in these cases), Whitley moved to D.C. looking for government work, and soon got a temporary appointment as a special agent for the Treasury Department. Two years later he was named head of the Secret Service, which had been established only four years earlier, and was primarily used to detect counterfeiting.

Around this time the Klan, which had been established in 1865 by Confederate veterans, began a terror campaign targeting blacks and their white sympathizers. Supported by President Ulysses S. Grant and his allies in Congress, Whitley realized that in order to fight the Klan he had to infiltrate it and convince its members to turn against each other. “He was great at creating covert operations, and he had a knack for deception, disguise, and creating plausible deniability,” Lane told the Beast.

Whitley did more than that—he created the conditions that eventually culminated in the prison at Guantanamo. He and his men arrested suspects and material witnesses, then sent some of them to Fort Pulaski, on the Georgia coast near Savannah, where they were to be interrogated. He then placed previously isolated prisoners in a cell together, listened in on their conversations, and told them that if they did not confess their guilt, they would never be free until they did. And if they did, he could guarantee them a new life under government protection, thus creating the first witness protection program.

“Whitley was way ahead of his time in believing if you’re fighting terrorists you have to get them to confess, and the best way to do that is to isolate them,” said Lane. “The instinct he had to understand basic human emotions is very impressive. He didn’t waste a lot of time on lofty concepts.”

In fact, Whitley was not averse to early forms of psychological torture. In the case of two black men who were reluctant prosecution witnesses, Whitley threatened to shoot one of them with a cannon, and the other man he forced into a “sweatbox” for more than 24 hours. As Whitley himself put it, “in localities where the masses are defective, where the local police are governed by the popular prejudice and where every stranger is looked upon with suspicion, all routine methods of detection become useless and must be superseded by entirely new and original modes of procedure.”

There is little doubt that Whitley’s “original modes of procedure” had their effect. By late 1871, Klan violence in Alabama and the Carolinas, the main areas of the Secret Service’s operations, had practically ceased, and thousands of Klansmen had been arrested and indicted.

But in 1872, an election year during which Grant needed Southern votes to secure his re-election, the president and his administration felt that Whitley’s crackdown was simply an emergency measure that had stopped the violence, and could be scaled back. Whitley vehemently disagreed.

After Grant was re-elected (and carried eight of 11 former Confederate states), “a major feature of Grant’s second term was ‘we forced these guys to back off, now we can approach them with amnesty and pardons,’” said Lane. “Whitley was one of the very few who never believed you would win these people over with concessions. Because he was tapped into his agent’s reports, he knew better than [Grant and his advisers] did what they were dealing with. He felt we have to smash these people, crush them.”

That never happened. Eventually, many Klansmen were pardoned or served their sentences and resumed their violence, as Whitley had predicted. But by this point, tainted irrevocably by a bungled 1874 safe cracking intended to smear a political opponent, Whitley had resigned as chief of the Secret Service. He eventually moved to Emporia, Kansas, where he became a successful hotel owner and died, a forgotten man, in 1919.

Whitley lived in a different time, and many of his methods would be anathema today. “All the stuff that involves gathering evidence without legal procedures would be impossible,” said Lane. “To the extent Whitley’s agents gathered any physical evidence without warrants, that would be thrown out, and the Miranda warning would influence things.”

But Fort Pulaski definitely led to Guantanamo and the concept that you don’t necessarily have to follow the letter of the law when interrogating terrorists (waterboarding, anyone?). Still, said Lane, “even if you’re against the Klan, you could have misgivings about using covert methods to destroy them. But you can’t have a serious national state without having this capability.”

And there’s this: “If you are faced with a terrorist threat,” added Lane, “whether domestic or foreign, you must have a clandestine ability to fight it, and it must be organized lawfully. And fighting the Klan was the first time the United States had to deal with that.”