Scandal in Oz: Was “Over the Rainbow” Plagiarized?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Norwegian pianist Rune Alver carefully unfolded the brittle sheet music and began caressing the keys of the baby grand. He had found the classical piece buried in an archive and believed it hadn’t been heard in maybe a century. But as he delved into the second section, Cantando, he felt a shiver run down his spine. The melody wasn’t just reminiscent of something he’d heard before — it was iconic. He instantly recognized the unforgettable, yearning opening notes of “Over the Rainbow,” the Academy Award-winning anthem Judy Garland performed in The Wizard of Oz, perhaps the most famous song to come out of Hollywood. How could this be? The sheet music was dated 1910, and The Wizard of Oz premiered nearly 30 years later. But the melody hung there (“Somewhere over the rainbow, way up high …”). It was hauntingly similar. Too similar, he thought.

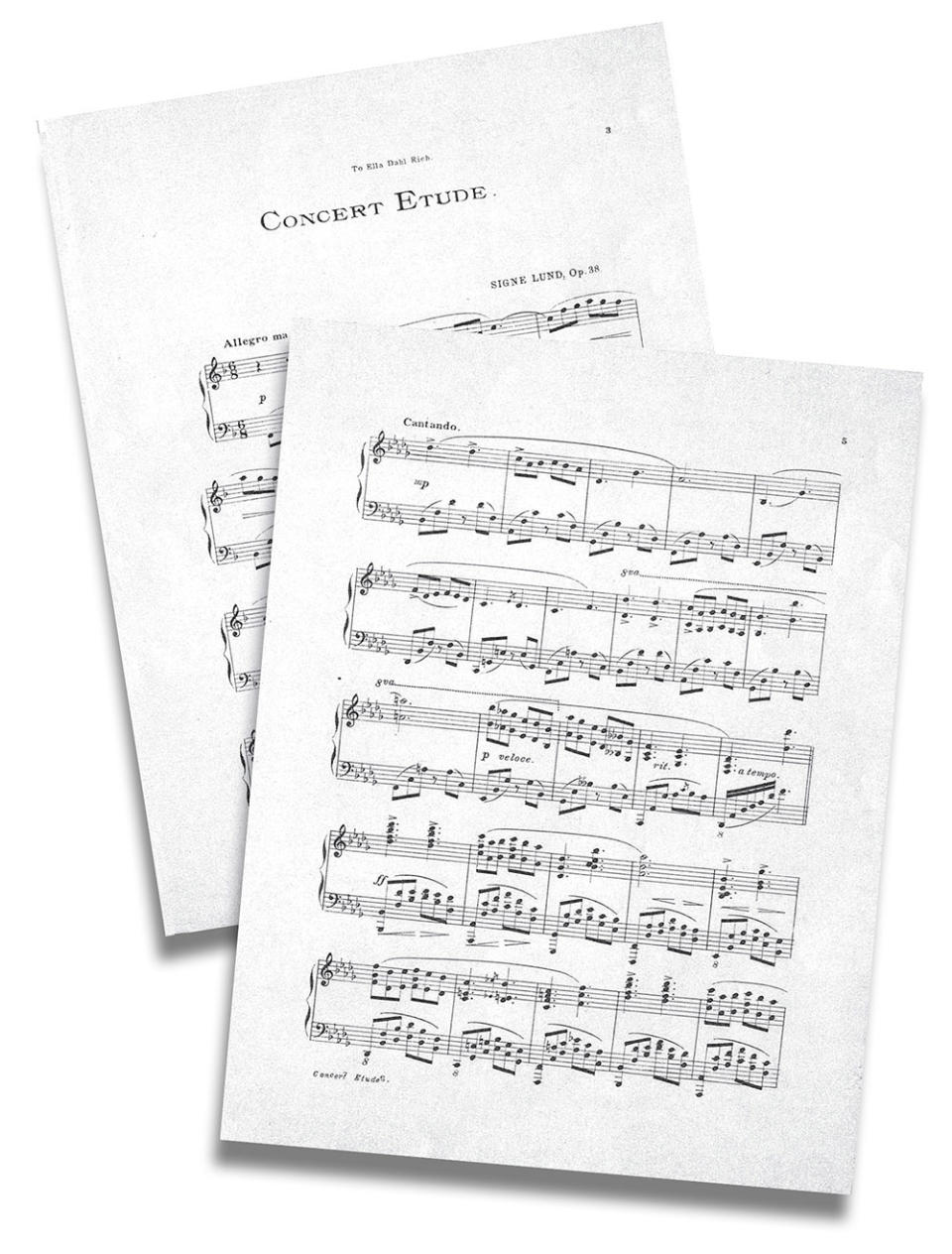

About 10 years ago, Alver, now 67, was researching the works of a Scandinavian composer named Signe Lund when he made this disturbing discovery. In the late 19th century, Lund had been the toast of Oslo and went on to a successful career in the United States, before her Nazi sympathies late in life turned her into a pariah. She was now long forgotten. It was at an archive in Bergen, Norway, that Alver unearthed the pages of her composition titled “Concert Étude, Opus 38,” which she had written in the United States and copyrighted in Chicago in 1910 during one of her visits to America. Lund had performed the piece in many American cities. It was “the most popular of her pieces” in her lifetime, Alver says.

More from The Hollywood Reporter

Paola Cortellesi's 'There's Still Tomorrow' Leads Italy's Donatello Awards Nominations

CBS, Golden Globes Set Nominations, Ceremony Dates for 2025 (Exclusive)

Webby Awards: Taylor Swift, Timothée Chalamet, 'Barbie' and The Hollywood Reporter Among Nominees

The similarities between Lund’s “Opus 38” and composer Harold Arlen and lyricist E.Y. “Yip” Harburg’s “Over the Rainbow” cannot be dismissed. Though there are notable variations (the former is in a minor key, for example, and follows a different time signature), the melodies of the main themes are nearly identical. Decades after the deaths of Arlen and Harburg, it is impossible to unequivocally determine whether the similarities are unintended or deliberate — a notoriously difficult thing to prove even when all participants are living. But to Alver, who included “Opus 38” on his 2020 CD Étude Poétiques: Works by Signe Lund, there is no debate about it. “Of course it is plagiarism,” he says today. Given the sacred aura that surrounds “Over the Rainbow,” the accusation borders on the blasphemous, akin to smudging the Mona Lisa. Yet Alver has no doubt that Lund’s DNA can be found in Harold Arlen’s melody.

Born in Oslo in 1868, Lund began her music career early. By age 4, she was already composing and developing a style that would later be described as lyrical and melancholy. Her studies in her teens took her to Germany, France and England, where she honed her musical talents. As an adult, Lund became a forceful advocate for women’s rights in all areas of society, including the music world, in which female composers were few. Her interests led her to found the Norwegian Society of Composers. At the turn of the 20th century, she abandoned her husband and three children to embark on a career in the United States, arriving first in New York and later settling in Chicago, with frequent voyages back and forth between the States and her homeland. During her time on U.S. soil, Lund pursued her activism, becoming a tenacious advocate against poverty and injustice. Lund composed and performed prolifically during these years and also served as a foreign correspondent for the Norwegian press, a guest lecturer, a music teacher and a fundraiser for humanitarian organizations.

In 1913, Lund was one of the first women to be bestowed Norway’s highest honor, the King’s Gold Medal of Merit. Always poised and elegant, she traveled throughout the U.S. to deliver more than 150 music lectures and both large and intimate society recitals, where she played her own classical compositions for receptive crowds. While in San Francisco in 1926, she offered the San Francisco Examiner Sun a prescient opinion of a current wave of music sweeping America: “I think jazz will find its level … and when it does the national music of America will have been born. I expect to become quite a jazz fiend.”

Lund returned to Norway in 1926 for the last time, and for a while lived her life in Oslo as a respected citizen and grandmother. But Lund’s outspoken support of socialism and subsequent allegiance to the Nazi regime during World War II led to her fall from grace. Norway shut the door on both Lund and her music. “After the war, it affected her a lot,” states her great-great-granddaughter Trude Sveen. “She lost her voting rights in Norway and they wanted to forget her. She wasn’t talked about. She was banned from the music world and not welcome at the Norway composers’ union anymore. Her music was not allowed to be played.”

Lund never renounced her affinity for Nazism before her death at age 81 in 1950. “In music milieus, she has a name,” says Alver, “but unfortunately, this name and all her very interesting music and life story are overruled by her Nazi imputation during the Second World War. And that is what people know about her. So, with my recordings, my idea was to give a better light on her, a more wide perspective on her music, and on her personality.”

Behind the Curtain

Harold Arlen’s formative years read like the story of The Jazz Singer. Born Hyman Arluck in 1905, he hailed from Buffalo, New York, where his father was the community’s most prominent cantor. At age 11, Arlen studied classical piano under the tutelage of Arnold Cornelissen, a well-known local musician and conductor. After a few years studying the great composers, including his favorite, Chopin, Arlen discovered a passion for the modern sounds taking over American music. “He always had that ear for jazz,” says his son, Sam Arlen. “That really sparked him.”

Arlen began composing his own music in his early 20s. His massive catalog would come to include such standards as “Stormy Weather,” “That Old Black Magic,” “It’s Only a Paper Moon,” “I’ve Got the World on a String,” “Come Rain or Come Shine,” “Accentuate the Positive” and his debut hit, “Get Happy.”

It’s fair to wonder why such a prolific composer would bother pilfering melodies from others when so many great musical ideas came naturally to him. However, in a 1932 article in the Buffalo Evening News, one reporter observed that the first song the 26-year-old Arlen tried to sell “was the sort that could have gotten him into several plagiarism suits.” That early accusation may have haunted the young composer for the rest of his career. Decades later, lyricist Yip Harburg reflected to Arlen’s biographer Edward Jablonski that his famous collaborator “was frightened of everything [he wrote] sounding like something else.”

It is entirely possible that Arlen was exposed to Lund’s work in his youth. In September 1917, while the 12-year-old Arlen was deeply immersed in studying classical music, Lund was touring upstate New York and made a weeklong stop in Buffalo. She performed a concert for the Spencer Kellogg family at their home, with several invited guests, according to her autobiography. The Kellogg family was one of Buffalo’s wealthiest and a major donor to the Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra, where Arlen’s teacher Cornelissen was the primary conductor. It is conceivable that Cornelissen introduced his young protégé to the music of the international composer visiting at the time. In addition, in 1920, Arlen was employed as a “song plugger” at Murray Whiteman’s Music Shop in Buffalo; his job was to introduce tunes on the piano and help promote the sale of sheet music. One can only imagine how many arrangements must have passed through Arlen’s skilled fingers.

The View From Oz

Listening attentively to Lund’s “Opus 38” for the first time, theater composer Stephen Schwartz seems more surprised to hear that it originated from a female European composer than by the possibility that it might have inspired “Over the Rainbow.”

“Oh, I like that,” he shoots back.

Schwartz, like Arlen before him, has composed numerous Broadway hits, including such enduring sensations as Pippin, Godspell, and the Wizard of Oz prequel Wicked. “Oh, of course I can hear the similarity,” he offers. “I would strongly challenge whoever said that this is plagiarism. If the question is ‘Did Arlen deliberately take this?,’ I’d lay very, very long odds that he did not. … I think it’s, of course, a curiosity,” he says. “It is interesting. What I would suspect happened is one of two things: I’d say it’s a coincidence, or maybe possibly something that Arlen heard or played when he was young, and it just became part of the palette from which he drew.”

As an unabashed fan of Arlen and Oz, Schwartz concedes there are undeniable commonalities between Lund’s and Arlen’s compositions, but adds, “If this was a different composer or in different circumstances, I might be a little more suspicious of something untoward having occurred here, but I think it’s extremely unlikely.”

Schwartz is not the only one whose ears pricked up when they first heard the Cantando to Lund’s “Opus 38.” Michael Feinstein, the polished pianist and recording artist who founded music-preservation nonprofit The Great American Songbook Foundation, recognizes the likeness as well. “Well, it’s very similar, of course, to ‘Over the Rainbow.’ But there are only 12 notes on the piano,” he explains. “My take on it is that Harold never would have knowingly stolen anything. It’s not hard to prove any theory when it comes to music. There is a famous saying that ‘plagiarism is copying without inspiration, and inspiration is plagiarism without getting caught.’ ”

Notes Schwartz, “These things happen all the time. More often than not, they’re inadvertent. There’s a little two-bar thing in one of my songs from Pippin, which years later I discovered, to my horror, was very similar to something in [the Puccini opera] La Bohème and was totally not deliberate. But, of course, these things are in your ears. Many, many people have had the enjoyable experience of going through Andrew Lloyd Webber and pointing out the Puccini references in his work, Stephen Sondheim and pointing out all the Ravel, and many people have gone through Leonard Bernstein and pointed out Aaron Copland. I think this sort of falls in that category.”

Schwartz is quick to differentiate between deliberately lifting or borrowing melodies and the inclusion of existing works, such as the intentional nostalgic Easter eggs he hid within the greenery of Wicked. Listen carefully, and you might hear Schwartz pay tribute to “Over the Rainbow” in the musical’s “Unlimited” theme for Elphaba.

Entertainment attorney Jane Davidson of Los Angeles firm Munck Wilson Mandala is less equivocal: “Yes, you have a sound-alike.” With experience as a practicing lawyer and adjunct professor at the USC Thornton School of Music, Davidson brings valuable insights into plagiarism cases within the music industry. She acknowledges that if this matter occurred and were litigated today, she would “probably” take this case. According to Davidson, one of the factors of assessing the similarity of two songs is that the similarity is not “De minimis” or too small to be meaningful. Davidson said, “this definitely sounds like more than that.”

Davidson emphasizes that one of the keys to forensically proving plagiarism is demonstrating “access.” She says, “You don’t have to show that this person sat down at their piano with the sheet music for this song and they played it. But was there somebody performing this song at a concert venue in their area, and is there a good chance that this person potentially went to see it? That would be something that could give rise to ‘innocent infringement,’ which is usually the term people use.”

Even Sam Arlen, who oversees his father’s estate, bows to the recent finding. “There’s no question. You hear it, certainly,” admits Arlen. “Whether it was intentional, no one knows. Sure, anything is possible. With the difficulty he was having with the song initially, and enough people around to listen to it, surely somebody could have said, ‘You know, this is very similar to this piece.’ It’s all conjecture.” His father, he says, had an antidote to such unintentional filching. “Harold would not listen to other music when he was working on projects. He blocked out everything around him just to be in his zone with what he was working on.”

“It Came Out of the Blue”

The Wizard of Oz was well under way at MGM Studios in the spring of 1938 when Arthur Freed, an uncredited producer on the project, sent a memo saying the movie needed a standout ballad for their young star, Judy Garland — something grabbing, equivalent to Snow White’s hopeful “I’m Wishing.” Freed, a songwriter himself, had passed on many of the seasoned composers of the day in favor of hiring the relatively unknown team of Harold Arlen and Yip Harburg. In her 1977 book The Making of The Wizard of Oz, the first serious publication to examine the brains and the heart of the motion picture masterpiece, author Aljean Harmetz noted: “Harburg and Arlen were hired on May 19, 1938, on a ‘flat deal,’ a fourteen-week contract. … Arlen and Harbug wrote an integrated score in which every song commented on character or advanced the plot.” Though neither of them had read L. Frank Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900), the children’s book upon which the film was based, they were exactly who Freed wanted. The pair first tackled the “lemon drop songs” such as “If I Only Had a Brain” and “Ding-Dong! The Witch Is Dead.” By the time they’d completed most of the songs, they began to panic because their contract was rapidly expiring and they’d yet to get a handle on the indispensable main ballad for Garland.

Years later, Arlen recalled his eleventh-hour inspiration in an interview with the BBC: “We finished all of the songs that you know, except ‘Rainbow.’ And I had a very hard time with it. And Arthur Freed wondered why I was so anxious and full of anxiety about this particular spot. … And I told Mrs. Arlen at the time, I said, ‘Let’s go to Grauman’s Chinese and see a picture, and you drive, I don’t feel like driving.’ And we passed Schwab’s. This thing came to me, and I wasn’t looking for anything. My mind was far away from work — or I think it was. And I tell my wife to pull over and I put it down, and that was ‘Over the Rainbow.’ It came out of the blue.” He would later tell his biographer, “It was as if the Lord said, ‘Well, here it is, now stop worrying about it.’ ”

Harburg remembered that Arlen called him that night and told him about his epiphany. Harburg rushed to Arlen’s home but was disappointed when he heard the initial eight bars of the nascent melody. In later years, Harburg would recall to various sources that he had thought the tune had “such symphonic sweep and bravura … It’s a great big theme that you could easily build a symphony around … It’s full of crescendos! It’s too lush!”

Reaching an impasse on the new melody, the team sent a plea to their longtime friend, composer Ira Gershwin, to arbitrate the matter. Gershwin liked what he heard, but suggested Harold play it with more rhythm, which the group agreed sounded much better when implemented. Harburg claims to have suggested a bridge for the middle of the song, which is later repeated at the end. Interestingly, the eight-bar melody that Arlen would first play for Harburg, the one that sounded too symphonic and came from out of the blue, is precisely the section that so closely mirrors Lund’s work from 30 years earlier.

Once the melody was set, Harburg got to work on the lyrics. “I knew I wanted something with ‘rainbow’ in it,” he recalled. Though the Baum book never mentioned a rainbow, Harburg felt that it was the perfect metaphor to “express the situation of a little girl who wanted to fly away from home, to go somewhere with more life and color than drab Kansas.”

Judy Garland recorded her most famous song on Oct. 7, 1938, and the sepia-bathed sequence was filmed months later, in February of 1939, directed by an uncredited King Vidor. While an imaginative MGM press report noted Garland would deliver the song sitting atop a giant rainbow, it’s clear that this concept was never intended for the final production. Mercifully, the film opted for a heartfelt rendition, with Dorothy conveying a genuine sense of longing accompanied by her faithful companion Toto.

Harburg fell in love with Garland’s performance, telling interviewer Dick Cavett in 1978, “She was a most unusual, quick study. She could sit at a piano with Harold Arlen, and Harold would play the song for her and before he was through, she knew it. … Her innate feeling, her intuition, and, of course, she had a voice. I think it was one of the rare voices of that half-century.”

Defying Gravity

As powerful and poignant a performance as Garland’s “Over the Rainbow” is in the film, it’s hard to imagine how fragile the song was in its infancy. At sneak previews of The Wizard of Oz in the summer of 1939, audiences watched a markedly different version of the film than we have come to know. By the second preview, all traces of “Over the Rainbow” had been abruptly excised. “Harold and I just went crazy,” recalled Harburg in a 1973 speech. “We knew that this was the ballad of the show … this is the number we were depending on. We pleaded, we cried … we tore our hair.”

While historical accounts commonly point the finger at nameless MGM executives who protested that it was “undignified” for an MGM star to be singing in a dusty, bucolic setting, Harburg recalled it was the film’s director, Victor Fleming, who “walked into the office … and he said, ‘I’m sorry to say … the whole first part of that show is awful slow because of that number. We gotta take it out.’ ” Ultimately, however, producer Mervyn LeRoy was the one who wielded the ax.

“We decided to take action,” Harburg said. “We went to the front office, we went to the back office … there wasn’t a god around who could help us.” With “Rainbow” now vanquished — a decision supported by both the director and the producer of Oz — who would emerge as the song’s savior? None other than the man who first championed Arlen and Harburg from the beginning: It was Arthur Freed who bypassed Fleming and LeRoy and appealed directly to the head of the studio, Louis B. Mayer, even staking his career on the matter. “The song stays — or I go! It’s as simple as that,” he is said to have demanded. Reluctant to lose his rising star producer, Mayer granted the song a reprieve, and it was reinstated. Freed was vindicated when Arlen and Harburg took home the Academy Award for best song of 1939.

Now, on the 85th anniversary of the film, nothing could be truer: If ever there was a song that was intertwined with its performer, it would be this one and the incomparable Judy Garland. “It has become part of my life,” Garland said of the song in the early 1960s. “It is so symbolic of everybody’s dream and wish that I am sure that’s why people sometimes get tears in their eyes when they hear it. It’s still the song that is closest to my heart.” And as it happened, “Over the Rainbow” was the final number the entertainer performed before an audience during her last concert, in Denmark in March 1969. She would die just three months later.

The ballad has been interpreted and recorded by hundreds of singers over the decades, from Frank Sinatra, Ella Fitzgerald, Ray Charles and Tony Bennett to more modern versions by Hawaiian performer Israel Kamakawiwo‘ole, Ariana Grande, Trisha Yearwood and the famously soulful rendition by Patti LaBelle.

Feinstein evaluates its profound status like this: “A song as overexposed as ‘Over the Rainbow’ became overexposed because of the love and adoration somebody has for a piece of music. And, certainly, it’s because of its unique position of being in a movie that has become beloved and classic. It’s probably the best-known multigenerational song in our country, maybe best-known song in America. That and ‘Happy Birthday.’ I mean, it’s come to that level.”

Shadow of the Rainbow

With all participants long dead, one can reasonably wonder why it matters exactly how the melody landed in Harold Arlen’s imagination, since it is his version that now resides in the hearts of untold millions.

Signe Lund’s greatest ambition, according to her diaries, was to have her work be recognized and appreciated on an equal footing with that of male composers. “Over the Rainbow” might just have been that fulfillment in some strange way. In this case, there remains no smoking gun to prove either side of the authorship question. Yet so many questions remain; the true authorship of “Over the Rainbow” can be argued but not decided. The family of Lund seems content in knowing their ancestor’s melodies are now being rediscovered. “As far as I know, nobody has discussed litigation,” says Sveen, who resides in Rakkestad, Norway. “Me and my family are grateful that Signe’s music has gotten more attention in recent years. I wish my great-great-grandmother had experienced it when she was alive.”

When Arlen died in 1986 at age 81, many of his friends recalled how reclusive he had become, especially in his final years. Arlen rarely granted interviews or dealt with the press. It just wasn’t him. “Harold is a very, very melancholy person,” Harburg said in the 1970s. “Behind every song Harold writes is a great sadness … Even his happy songs. You can take a song like his rousing hit ‘Get Happy.’ Sing it slowly. Examine it. It’s painful.”

His son, Sam, says Arlen was not aware of the extent to which “Over the Rainbow” would overshadow the rest of his oeuvre. “Every writer strives for one song that is going to define their legacy. I don’t think he ever knew what song that was going to be,” Sam says. “He definitely didn’t know that ‘Over the Rainbow’ would take on the life it did. He was not one to speak much. He just wanted to write, and he always felt that his music would do the talking.”

This story first appeared in the March 6 issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Best of The Hollywood Reporter