With ‘Saw X,’ Composer Charlie Clouser Dethrones John Williams to Make History

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

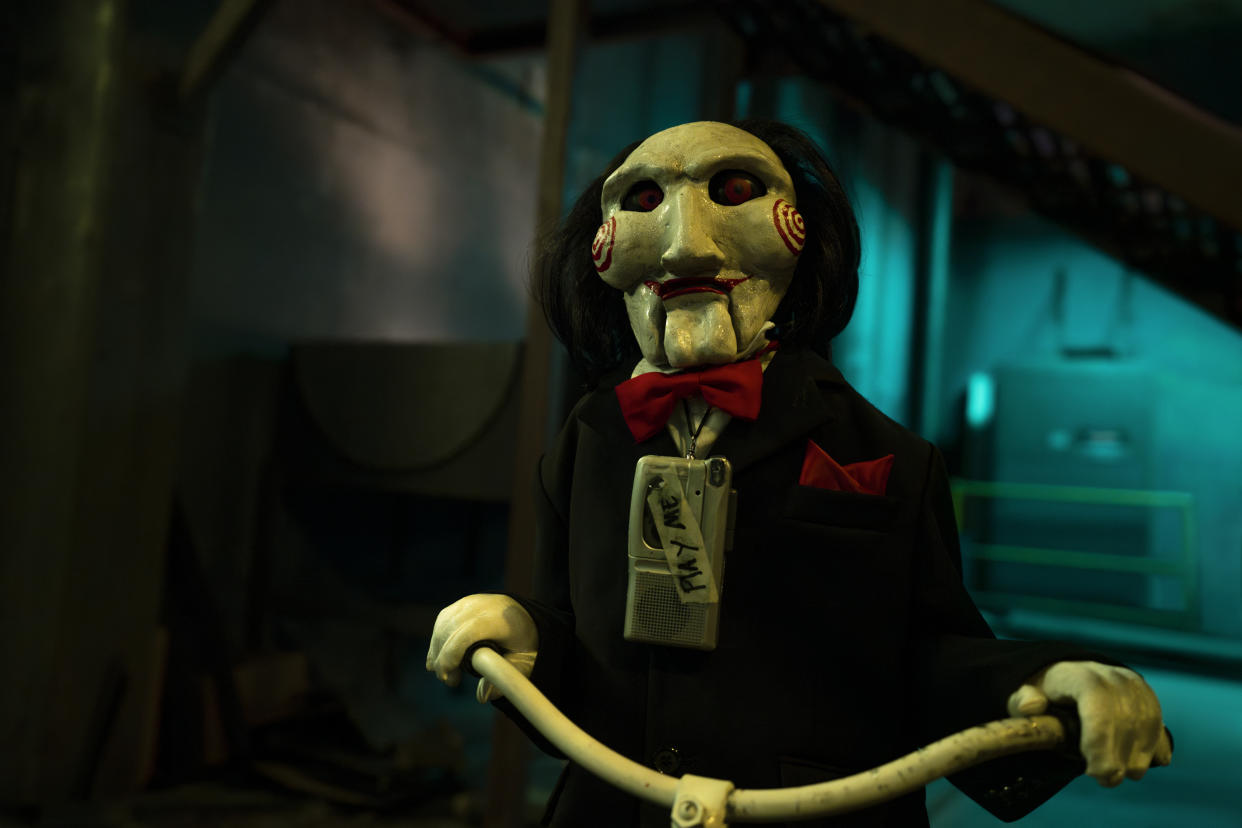

Composer Charlie Clouser entered the history books twice in the past year: first for being inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame as a member of Nine Inch Nails, and second for scoring “Saw X.” Clouser has been with the “Saw” franchise since the first film in 2004, and by writing the music for all 10, he dethrones John Williams (who created nine “Star Wars” scores) as the U.S. composer responsible for the greatest number of consecutive U.S. feature film scores in one series.

Clouser isn’t one to rest on his laurels, however — “Saw X” contains some of his best work to date in the form of a score that retains the elements that made the other “Saw” movies great (including Clouser’s now-classic “Saw” theme) but leaps forward in new directions. “Saw X” is, in many ways, the most classical film of the series, one that explores new sides of John “Jigsaw” Kramer and thus requires a more varied, emotional score. Clouser talked with IndieWire about his work on “Saw X” and the franchise in general in a wide-ranging conversation.

More from IndieWire

Warner Bros. Fights With Itself as 'Blue Beetle' Vies with 'Barbie' in PVOD Battle for #1

Maya Hawke Duets with Ethan Hawke for Cover of Willie Nelson's 'We Don't Run' - Listen

IndieWire: Before we get into “Saw X,” I have to ask how you came up with the iconic “Saw” theme that became an integral part of all the “Saw” movie climaxes.

Charlie Clouser: Well, before I got started I did have some long conversations with the director, James Wan, about what that piece of music needed to do and what it needed not to do. We agreed that it did need to be bold and memorable and “hooky,” sort of like a tasty guitar riff, but it also needed to be somewhat simplistic so that it wouldn’t be too distracting. Whenever that theme appears in any of the films, there’s a ton of information flying at the audience, so it would be a bad thing if they got distracted by an overly complicated symphony coming at them. We knew that it needed to build in intensity and energy, moving in stages towards a massively epic conclusion while still staying anchored on the core melodic elements. So, that road map established the form, and then all I had to do was fill in the content. Simple, right? [Laughs] But, seriously, it did come fairly quickly once I had those ground rules established. I think I spent a day writing it, creating the string arrangements, and programming the electronic elements, and then another day recording the strings and mixing the final track. I’m still kind of amazed that it’s had such a long life across 10 movies and 20 years though!

What would you say were your guiding principles for scoring the “Saw” movies?

One thing that’s important to me is that the music feels like it’s happening in the same place as the scenes in the films. So if we’re in some dark, crusty, underground lair, then I want to use sounds that feel like they’re in that same claustrophobic place. That’s why I use a lot of dark sounds, bowed metal instruments, and industrial drum elements. Another guiding principle that I try to use is to have the main chord progressions and melodies moving downwards through most of the score, as if the music is helping to drag the viewer down into the depths of whatever the victims are going through. Then, when I reverse direction and start moving upwards, it’s a big contrast and hopefully hits a little harder.

“Saw X” shifts the point of view somewhat to favor John Kramer more than the previous films, where he was largely behind the scenes. How did that inform your approach to the score?

It is unusual for a “Saw” film to spend so much time on John Kramer’s backstory and to take an almost sympathetic view, but that gave me the opportunity to use some sounds and musical ideas that wouldn’t have felt right in any of the previous movies. So for that part of the film, I did take a much more gentle approach than ever before. But even though there are a lot of those non-typical elements to the first third of the score, I still tried to use some of the chords and melodic intervals from the larger “Saw” musical landscape, but played on sounds that were lighter and more bright, letting a ray of sunshine creep into John Kramer’s world. It makes the contrast when we inevitably descend into darkness even more pronounced.

The warm and hopeful moments are often the most tricky bits to get right. For me, just because the music is simple and light doesn’t mean it’s easy! Those spots seem to take as much time and effort for me as the most insane trap scenes. On the other hand, it’s always the case in the trap scenes that each one has to be unique and feel bigger and more crazy than the rest. I’ve turned the knob to 11 so many times that now it’s hit about 76 and it’s almost broken off! So the trap scenes are always a challenge because I feel like I really can’t repeat myself. Every sound needs to be something fresh and new that fits the visual vibe of the scene, and there are no common musical motifs that I can draw from for the trap scenes, with one exception: the quiet, descending bit after the trap is sprung and the victim dies.

How would you say the music in the “Saw” films has evolved since the beginning? Where did you want to stay consistent with what had come before, and in what ways did you want to strike out in new directions?

The music in the first film was quite simplistic in many spots and had a bit of a lo-fi aesthetic that seemed to fit the gritty look and feel of that film. As we progressed through the sequels, I’ve tried to follow the evolving visual style and scale of the production and art direction so that the more frantic and grandiose scenes had music that was bigger and fit with what we’re seeing on the screen. As different directors have rotated in to take the wheel on various sequels, they’ve each brought their own visual style to the films, and I try to follow along stylistically. For instance, Darren Bousman’s style felt a little more influenced by film noir and at times had an almost gothic feel, so I tended to write cues that had more bombastic elements like choirs and epic brass and used rising melodies that followed the way he constructs a scene.

In terms of the musical motifs, melodies, melodies and so forth, there’s a certain batch of chords and melodic intervals in my toolbox that are pretty much “Saw”-only, and even when I’m doing a cue that’s mostly ambient sounds with no strong musical content, I still use those shapes and motifs when triggering weird floaty sounds, and I’d like to think that helps keep even those sound-design-y moments planted in “Saw”-world. But there are certain little “musical molecules” that I pull from the archives, sometimes with new sounds, and sometimes with exactly the sounds I originally used, and those spots are intentional sonic throwbacks intended to remind the viewer of spots or moods in previous films. I hope that they come across as obvious nods to past films and stick out to the viewers as strongly as they do to me.

Are there any specific techniques that you think are unique to scoring horror?

I think dissonance and atonality are pretty crucial to the horror-scoring landscape, and they help to enhance the feeling of desperation and confusion that the victims in so many horror movies inevitably feel. The sound of the unknown threat, the desperation of searching frantically for an escape, and the frenzy of struggle… atonal screeching violins, dissonant low drones, and percussive “chomps” on low strings seem to enhance those feelings perfectly. The Bartok and Penderecki music used in Kubrick’s “The Shining” are great examples of that. Of course, we hear some of those elements in all kinds of scores when characters are threatened, from Indiana Jones to “The Batman,” so those techniques aren’t exclusive to the horror genre, but it’s true that in horror films you can really go to extreme lengths and really go for the throat sonically without it feeling like it’s too much. Then, when and if you do switch gears into a more melodic or thematic mode, it’s a bigger contrast and can have more impact, driving the story points home with a little more strength.

Who are some of the other composers who inspire you?

While they’re nothing like the “Saw” films, and their music is much more minimalist than what I can reasonably put in a “Saw” film, it’s all really cool stuff. There is the team of Danny Bensi and Saunder Jurriaans, who have scored “Fear The Walking Dead,” “Ozark,” “The Outsider,” and a psychological thriller I really love called “The Gift.” Their music is very minimal but still very effective and intriguing. Another composer named Mark Korven, who scored “The Lighthouse” and “The Black Phone,” does really effective music with amazing sound design. He actually helped to invent this weird instrument called The Apprehension Engine, which I saw him demonstrate in a YouTube video and I immediately began the quest to get one of my own. I eventually succeeded, and this strange beast can be heard on my score for “Saw X,” especially in the scene when Valentina is having a particularly bad time. That scene wouldn’t have been the same without the sounds of Mark’s Apprehension Engine.

I always love weird and experimental instruments, and another one for readers to go down the YouTube wormhole on is Chas Smith, who is an amazing musician and experimental instrument builder. His instruments have been a big part of all of my scores in the “Saw” franchise, going all the way back to the first film, and he’s also collaborated with Hans Zimmer on “Man of Steel” and other films, creating amazing textures and super-dark sounds. Get on that Google machine and search these folks out!

“Saw X” is currently in theaters nationwide.

Best of IndieWire

Where to Watch This Week's New Movies, from 'The Creator' to 'Fair Play'

The Best Thrillers Streaming on Netflix in October, from 'Fair Play' to 'Emily the Criminal'

Sign up for Indiewire's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.