Savannah's zine publishers eschew traditional routes for creative freedom, true authenticity

I got my first job at age 16, working at Dollar City, an “everything is a dollar or less” store, in Herndon, Virginia. Near the register we had a copy machine that did black and white only at a mere 10 cents per print. Every few weeks a young man not too much older than I would come in and set up on the table adjacent to the copier, printing copy after copy, then stapling them together into small booklets that he sold for $4 a pop.

He was creating what’s called a “zine,” and in the three decades since my first introduction to the form, it’s become more popular than ever, especially here in Savannah.

“I always look at zines as being largely self-published, largely done with economical materials, designed to be replicated en masse, without a large budget,” said Lee Heidel, owner of Neighborhood Comics and one of the organizers behind last October’s SAVage Fst Mini-Comic and Zine Festival. “In terms of content, it can be prose to poetry to comics to photography to special interest kind of work.”

That’s the freedom of calling something a zine gives you,” he continued. “It opens that up, and takes the idea of there being a limitation on your content away. It’s wholly yours.”

The Zine Scene

Neighborhood Comics’ Bull Street location carries a number of zines, prominently featured on an end cap that’s visible upon entering the shop. To those who know where to look, however, zines can be found at locations across the city, from the Sulfur Shop at Sulfur Studios/ARTS Southeast, to Original Skin Tattoos & Piercings, to E Shaver Booksellers.

Darriea Clark, the creative mind behind “Dear Diary,” a zine that, for its first issue, collected personal journal entries by 27 contributors, even orchestrated a full-fledged artistic event at Coastal Empire Beer Company for the release, featuring live music and readings by the authors who contributed to the project. For Clark, who studied magazine publishing at Syracuse University in New York, it’s her way of bringing truth to print during an era when the lines between fact and fiction are oftentimes blurred.

“When I was graduating from school, there was a really big push for influencers and people who worked in marketing to be authentic,” she explained of her decision to self-publish. “We hear that all the time in the social media space: Be authentic, be authentic, be authentic. And what I started seeing is that it was still this kind of packaged, aesthetic way of being authentic.

“This whole strive to be authentic just felt still very edited, very curated, very marketable, capitalistic; a sellable authenticity,” she continued. “I don’t want that packaged authenticity.”

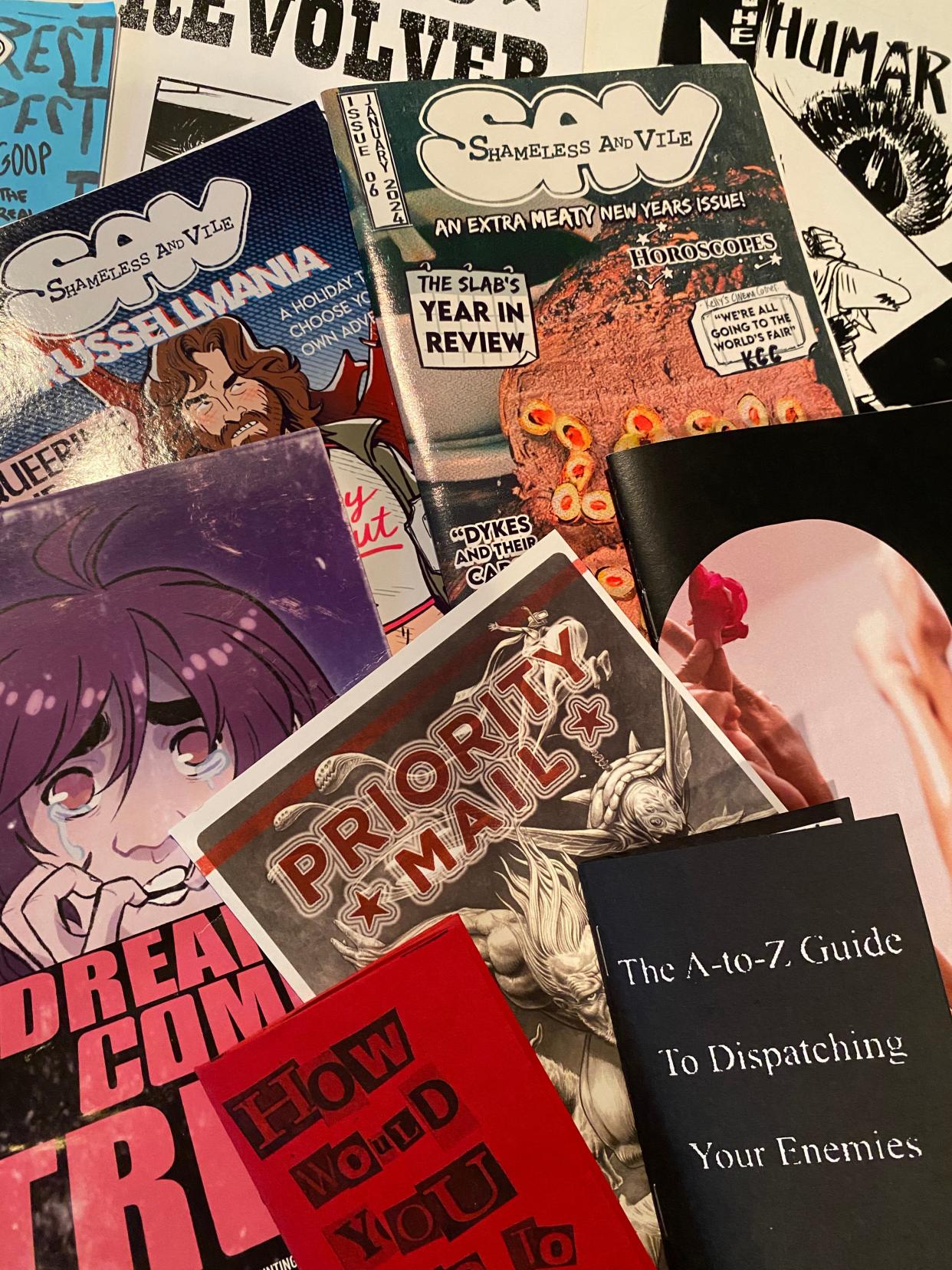

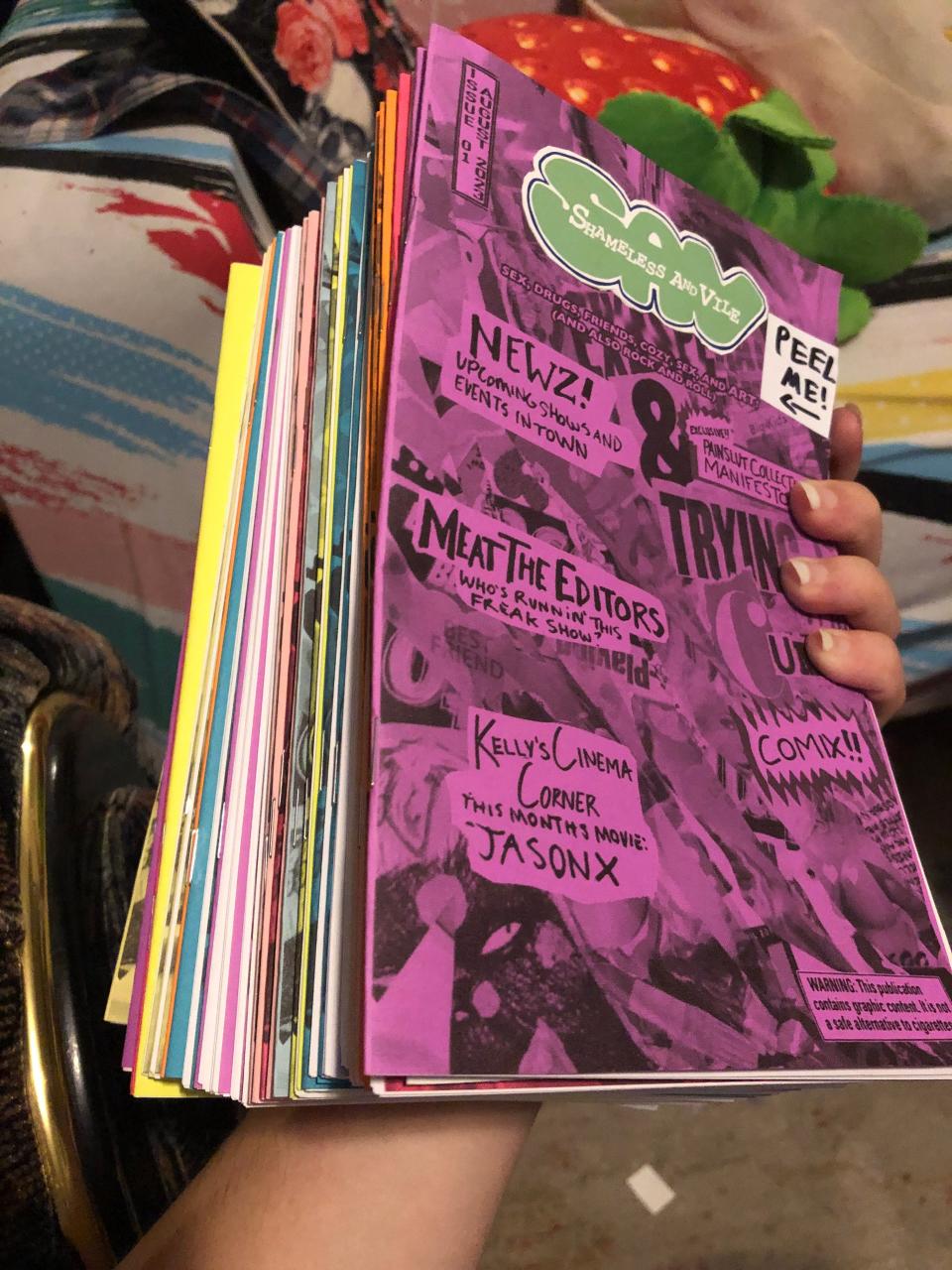

Similarly, Kiwi Byrd, Kelly ‘Kel’ Kovach, and Valentine Morris, the three young people behind the LGBTQIA+ friendly monthly zine “Shameless and Vile” (cleverly shortened to SAV), pair their releases to parties at “The Slab,” a callback to the cement-paved back patio of their house. Described by Kovach as “Mad magazine for people I like and know,” the zine format suits both the trio’s underground roots and their need to be able to use their voices without restraint.

“We’re doing something for Savannah that’s punk, queer, not unedited but unfiltered,” Morris said of Shameless and Vile. “We don’t put our stuff online, so we have no service to the algorithm. We don’t have to worry that our stuff is gonna get taken off Instagram because we say ‘whatever.’ We don’t have to worry that people aren’t going to see it, because we know who’s gonna see it, the people [who are] right in front of us who we are [telling] take it, take it, take it.”

“I feel like people talk [about] free speech, blah, blah, blah,” he added. “But online things are just taken down and extremely restricted for arbitrary reasons. You can’t talk about things that are real.

“It’s because it’s private property,” Byrd explained. “Because sites on the internet are private property. So, while technically free speech is legal, we’re in their yard. I don’t want to be in their yard anymore.”

Fellow zine-maker Ryan Rish is also leaning into her punk roots with “The Bakery,” although the artist has a few years on young upstarts Clark, Byrd, Kovach, and Morris. Like her cohorts, she has become disillusioned with the world of mainstream publishing, and has used the art form to showcase photographers and graphic designers like herself, without being beholden to other people’s demands.

“We’re no longer seen as the creative,” Rish said of the position that many with her background find themselves in. “We’re actually seen as the tactician, who’s going to show up and make your vision happen. And for a lot of us it’s why we burn out from the industry. It’s why we no longer give a shit, to be honest. You’re gonna pay me if I give you all my ideas, and you’re gonna pay me if I just do what you ask me to do, so what purpose does it serve?”

“I’ve had enough people tell me that I’m not good enough,” she continued. “I’ve had enough people tell me, ‘This isn’t really what the client wants.’ I don’t care what the client wants. I am the client, so I’ll do whatever I want. I can do whatever I feel is good.”

'It's a low pressure entry point'

In the cases of "Dear Diary," "Shameless and Vile," and "The Bakery," it’s about a collective of artists and writers coming together to enact a shared vision. But as was the case 30 years ago with the young man who spent hours at a time putting together his passion project at my Dollar City, more frequently zines are about an individual artist bringing their creativity to light.

“I just like that zines and mini comics are a do it yourself thing, and you can do it whenever,” said local zine and comic book creator Maria Pellegrino. “And you don’t have to wait around to be like, ‘Yes, I have connections, I’m getting it officially done.’”

The recent SCAD sequential art program graduate has what she terms “big girl jobs” as a colorist in the industry, the kind of thing that pays the bills and for which she was trained. But, she told me, “sometimes the art you’re paid to color is bad,” so zines allow her to showcase the kind of art that she really loves to create. And with titles like “How Would You Like To Die?” and “Dreams Come True?,” about a child who panics after believing one of nightmares is destined to become reality, the format is likely the only place she’ll ever see those particular ideas published.

“Fitting my content to the space is always a hard thing for me,” she said. “I don’t do the whole ‘follow trends’ stuff. I don’t have the energy, patience, or lifestyle for that. The way I live, it doesn’t make for good content.”

Printmaker and Illustrator Jordan Fitch Mooney, who has long been a part of the local zine scene, has frequently found himself in a similar position, where his artistic ideas don’t always fit into any specific category. He got into the form in the early to mid 2000s, and has used it from time to time when other avenues for showcasing his work, like traditional fine art galleries, aren’t a realistic option.

“The cost of making art is so prohibitively expensive sometimes, entry fees and framing and all that stuff, and I just didn’t have the money,” Mooney acknowledged. “But once I got into [zines], I can spend thirty dollars printing thirty copies, and take it somewhere and sell it. It was a way to be able to still make art, and some of it looks rushed and not great, but to make something and get it into peoples hands.”

Fellow solo zine-maker Ugis Berzins agrees.

“It’s not a problem to deal with editors and art directors, but if you want to do your own stuff, you have your own ideas, why wouldn’t you publish your own stuff?” Berzins asked rhetorically. “It’s easier than ever to do short run, professional-looking comics.”

“Printing now is so cheap, and you can do such small quantities and have it look legit,” he continued. “You can do it and be minimally invested, and still have a ‘thing.’”

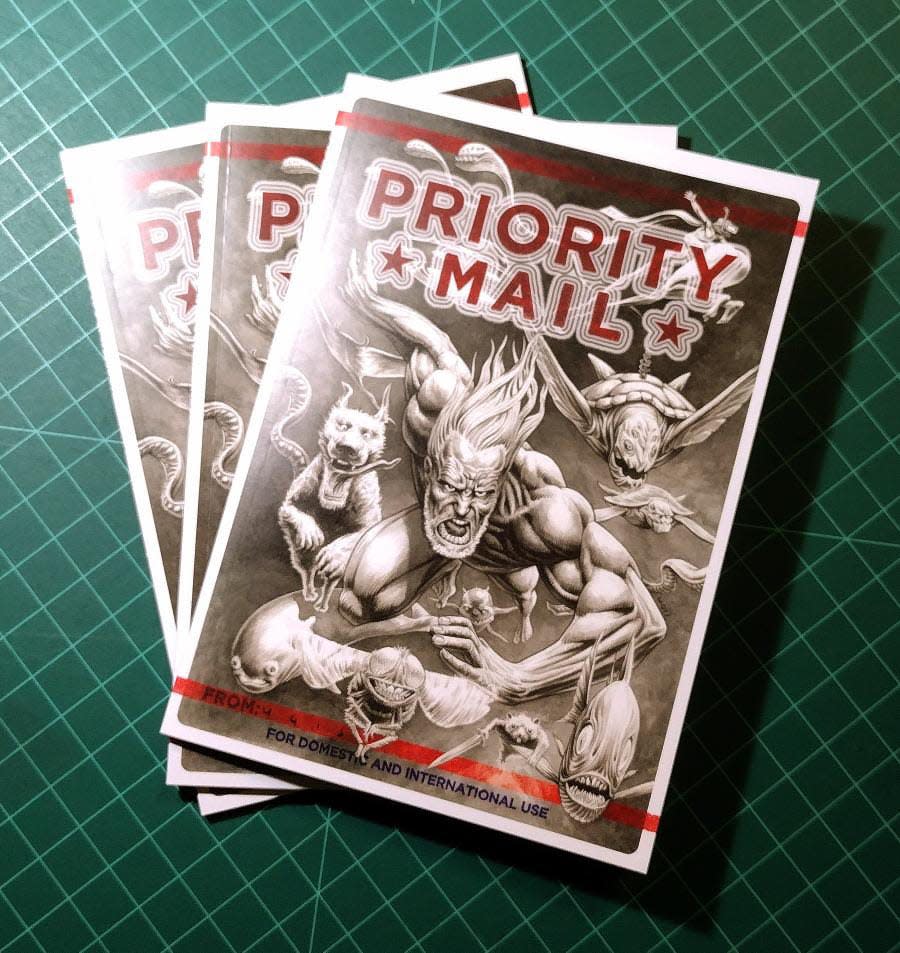

And as with Pellegrino’s “Die,” Mooney’s “The A-to-Z Guide To Dispatching Your Enemies” and Berzins “Priority Mail,” a printed collection of drawings he did on USPS shipping labels, are unlikely to find much traction with traditional publishers. But zines have allowed all three artists to be published, and to have a level of control that’s unheard of in the industry.

“It’s a low pressure entry point,” said Berzins. “Anybody can do it. There’s no rules. It’s cheap.”

An Art Form For Everyone

“A zine is freedom,” Rish proclaimed. “It’s the freedom to create whatever you want, because you’re making it.”

“It kept me alive artistically for a period,” noted Mooney. “It kept me from just giving up hope on making art.”

“For me, just making it, I work two retail jobs that I hate, but I have to do this art thing every month,” said Kovach of Shameless and Vile. “It’s good to have a deadline that I set for myself, and to have something that I know that I’m making and publishing, and I’m still moving towards what still is my goal, to have an artistic career.”

“There’s so much room for growth and it’s not crowded,” said Morris of the zine space in Savannah. “There is room for everybody to have their thing.”

Zines have been a part of the savannah creative culture since at least the early 1980’s, when the first SCAD students began self-publishing their ideas and spreading them via coffee shops, bars, and tattoo parlors around the city. And in those 40+ years, they’ve expanded from the kind of simple paper and staple creations I first saw at Dollar City when I was 16 years old, a style still employed today by folks like Pellegrino and Mooney, to the polished, professionally printed zines like Clark’s “Dear Diary” and Berzins’ “Priority Mail.”

But regardless of the form it takes, the essence of zines remains the same: They’re a way for artists to express themselves authenticity and economically, without the need for industry connections or mainstream ideas.

“I think it’s a really healthy thing that everybody thinks of it as a way to express yourself,” opined Berzins. “I think that any artist should try it. Why would you not? What’s the worst thing that will happen?”

“If you’re doing these things anyway, or you have a horrible message to spread, a terrible idea, just spread it.”

Find all of the artists mentioned here on Instagram @theslab912, @deardiaryzinecollective, @futurelandfillpress, @tacticalanxiety, @jdfmooney, @ryanrishphoto, and @nbrhdcomics.

This article originally appeared on Savannah Morning News: Creative freedom, true authenticity mark of Savannah's zine culture