Sarajevo Festival Director Jovan Marjanovic on How Film Can Unite a Divided Region

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The Sarajevo Film Festival was born during the Bosnian War, in the midst of the nearly four-year siege of the city. “I don’t know of another festival that was founded in a city under siege, in a city without running water and electricity,” notes festival director Jovan Marjanović, who didn’t experience the siege himself — a teenager at the time he was evacuated from the city and spent the war abroad as a refugee — but is keenly aware of the festival’s unique history and legacy.

From the start, Sarajevo looked beyond Bosnia and Herzegovina, seeing itself as a pan-regional event with the goal of reconnecting, and rebuilding, links between the countries of the former Yugoslavia that had descended into nationalist conflict and war.

More from The Hollywood Reporter

Iranian Director Saeed Roustayi Imprisoned For Screening Film 'Leila's Brothers' in Cannes

New Ving Rhames, Marion Cotillard Films Among Oldenburg 30th Anniversary Lineup

In the decades since, Sarajevo has expanded its scope, becoming a hub for Central Europe and beyond, and a meeting place for the film and television industry “from Vienna to Istanbul.”

Last year, in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the festival reached out to Ukrainian filmmakers to provide them with a platform to present their films and projects. That was Marjanović’s debut as festival director — he took over after two years as co-director alongside festival founder Mirsad Purivatra. For his sophomore effort, Marjanović is looking to firm up Sarajevo’s position as the region’s number one festival while adapting to meet the needs of a maturing, and still rapidly expanding industry.

Marjanović spoke to The Hollywood Reporter ahead of the 29th Sarajevo Film Festival, which runs Aug. 11-18, about the importance of remembering the past and the challenges of facing the future.

From an outsider’s perspective, Sarajevo, the film festival, seems so closely linked to the history of the city, particularly the history of the Bosnian War and the siege.

I know what you mean. I don’t know of another festival that was founded in a city under siege, in a city without running water and electricity. I think the story of the founding of the festival is something that is really in our DNA, it very much informs everything that we’re doing today. We just try to make the best festival possible, whatever the circumstances because it was never just about putting something up on a screen and calling it a festival. It was really about curating the best of cinema but it was about communication, about people exchanging opinions and discussing things, being creative together. It was never merely entertainment. It was always an active act of watching. So the festival today is still very much connected to this origin story.

The Sarajevo Film Festival is the largest in the region and the most important for the industry in Central Europe. What role do you see the festival playing in bringing the region today, despite the history of nationalism and separation?

The role is bigger than that of just a film festival. I don’t want to put this in some nostalgic type of framework, about recreating the past, the old Yugoslavia. We are forward-thinking, and looking to how these more fragmented markets can work together. Obviously, some of them are deeply connected culturally and linguistically. Others less so. But, again, historically there are links in this region reaching basically from Vienna to Istanbul. So for me, the connections are not just from within the former Yugoslavia, but also with Romania, Bulgaria, Greece and Turkey. With Albania, obviously. We really try to look at these, let’s say, smaller European markets that were a bit outside the European mainstream and give them a meeting place, a common platform. Now Ukraine has become part of that, because of what is happening with the war. We always wanted to be a platform for regional cooperation. Sometimes that means just within the former Yugoslavia because that’s what makes sense in the market. The media here is already really intertwined. You have a company based in Belgrade, or in Zagreb, or here in Sarajevo that covers all five or six countries. The business for TV series is definitely pan-regional. The countries of the former Yugoslavia co-produce on a regular basis now. That wasn’t the case when we started. We were promoting these practices as part of our mission. And now that they’re a reality, we want to enhance them and help them develop further. That’s very much what our industry programs are focused on, to discuss how we can provide market access points to various projects or professionals from this part of the world, either for them to work with each other or to move into other bigger European or global markets.

When it comes to our talents program, it’s about really bringing all the young professionals from this region to meet their peers and constantly rejuvenate the scene. I think what we’ve managed to do is really create an annual meeting point for the entire region. It’s easier for people to work together when they know each other and they meet regularly for some 20 years now.

The results are quite visible and stable, almost predictable. That’s why we are all about anticipating the next thing to focus on. So the TV series wave became a reality in the region about five to six years ago. But we anticipated it a few years before and already started helping producers develop projects so that they had sufficient material ready for when the broadcasters and telco operators decided to invest. Our co-production market, CineLink Drama, is now in its eighth year, and these series are coming out on a regular basis. We have shows like Jasmila Žbanić’s I Know Your Soul, which will be presented at the Venice Film Festival this year.

You’ve built up a lot of structure over the years, but what do you think the region needs going forward?

I think we need to enable bigger projects to get funding, bigger-budget projects with a higher production value. Both when it comes to films, but also when it comes to series. I think the national film funds and public broadcasters and the bigger telecom companies operating in this region will probably need to adapt their business practices so that they can more easily co-produce with one another and enable these more ambitious projects to get made. The markets are growing in terms of the theatrical business. Now the entire region has been multiplexed after a long time where we lagged behind other European markets, even Eastern Europe. Now we’ve pretty much caught up. The TV market has grown and is now completely digitized. Piracy is still a huge problem but that’s also changing. But what we need is to create the structures to enable the production of bigger-budgeted films and TV series through co-production. That and probably reduce the volume of series being made, because there is an overproduction at the moment. We probably need to focus on a couple of bigger, better shows that can travel outside the region while also capturing the imagination of the audiences in the entire region.

We want to see a telecom company from Serbia and a telecom from Bosnia, do a show together which would double the budget and make it more ambitious. Because our budgets, right now, are so small. A Western European show probably has a budget of more than €1 million ($1.1 million) per episode. Even in Eastern Europe, the shows are around €500,000 per episode. When you come here. They’re about €200,000 per episode. So there’s still room to grow.

This is a difficult question to answer, but do you see any overall themes linking the films in this year’s program?

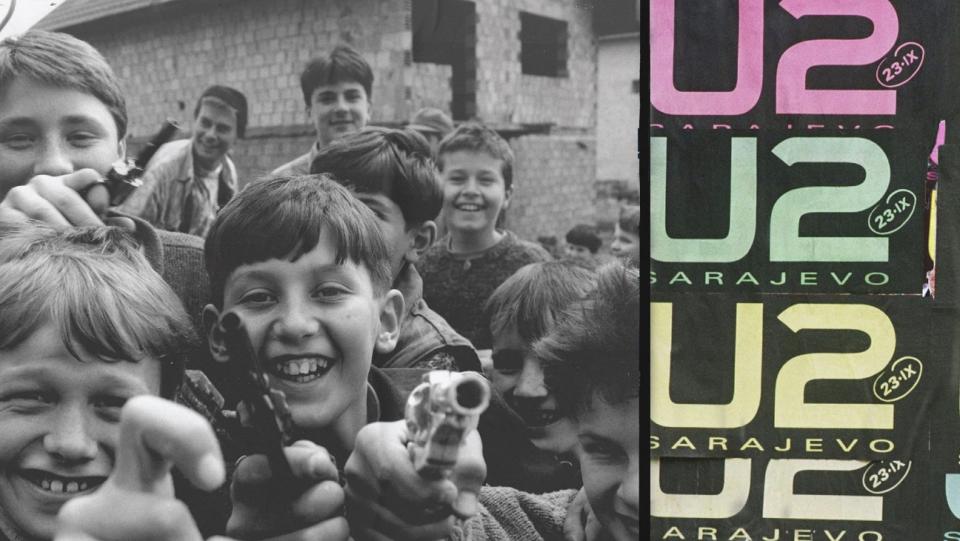

It is a hard question. Of course, we are opening with a film, Kiss the Future by Nenad Cicin-Sain, which is obviously very much linked to Sarajevo because it’s about the underground, literally underground, alternative scene that came up during the siege and had this crazy idea to try and attract the attention of the band U2 to get them to focus on what was happening in Bosnia and have a concert here. And then, after the siege, the concert actually happened and it was a kind of cathartic moment in the history of the city. It was like that moment marked the end of the war. The film has played in Berlin and it opened in Tribeca, and I watched it at both festivals but I feel the film’s true home is here in Sarajevo. I think the opening will really resonate.

For the rest of the program, if I can give a brief overview, we obviously have this regional theme. Sarajevo is focused on the region. We always have the biggest selection of films from southeastern Europe that you can see in one place, anywhere in the world. These are our competitive sections, so narrative features, documentaries, short films and student films.

In our competitive sections, we look for daring and challenging cinema. But we also want to show everything that’s been produced in Bosnia, so we have a program to show the entire yearly production from this region. In our open-air section, there’s a focus on more mainstream films coming from the region. Our flagship international section, which attracts over 3,000 people every night in a huge, open-air auditorium, is really about showing the best of world cinema of the past eight months or so. The best recent films that captured attention at Cannes or in Berlin or in Sundance. Then we have the summary screen and kinescope sections which really explore the global cinema at the moment. Kinescope is more about new styles of cinema and summary screen is, let’s say, more classic art house movies. Then there are our teenage programs and our children’s program. So we try to cover everything. But I can tell you that we received over 1,200 submissions this year from the region alone, the increase has been enormous. Partly that was because of a backlog of films and projects that didn’t get made during the pandemic, but also from other festivals not really looking at the region. There wasn’t a single Romanian film in Cannes this year, which hasn’t been the case for the past 10-15 years. So we had a lot to choose from.

One of the sections unique to the Sarajevo festival is the “Dealing With the Past” section, which looks at films that examine difficult periods in a nation’s history. This year it includes films like Mark Cousins’ March on Rome about Italian fascism and Georg Zeller’s documentary Souvenirs of War. Do you think the festival, because of its unique history, can help other cultures look at the troubled periods in their past?

Hopefully. There’s so much history in this city that is tied to destruction, to the ghosts of the past. The city is just filled with it. Obviously, we need to deal with that and sometimes we manage and sometimes we don’t, but it is definitely something that we are conscious of. So we hope we can help. And you know, what we see when we show these films is that very often, it’s much easier to open up and discuss your own past when you are faced with a similar example or a thought-provoking example from another culture or from another place in the world.

This is a program we take very seriously. Every year we bring together about 80 youngsters, people in their late teens and early 20s, from different countries in the region, to take part in this program, to look at the films and to discuss them. They’re mostly people who are active in some kind of civil society organization in their home countries. They are active audiences, people who want to discuss these issues. I try to participate in as many of their discussions as I can and those are usually the highlights of my festival. Especially when I hear back from them. Sometimes we meet a couple of years later and people tell me their stories, about the friendships they made here. It’s not so easy for an Albanian youngster and a Serbian youngster to come together — they don’t have many places where they can meet under normal circumstances. I think we have to be diligent about this and be active in talking about and dealing with our past. All the time. It’s almost like a form of mental health hygiene.

Interview edited for length and clarity.

Best of The Hollywood Reporter

10 Times Hollywood Predicted the Scary (or Not So Scary) Future of AI

21 Actors Who Committed to Method Acting at Some Point in Their Career

Every 'Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles' Movie Ranked, Including 'Mutant Mayhem'