When Sam Shepard Met Bob Dylan: Sex, Drugs and a Clash of Egos on the Rolling Thunder Tour

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

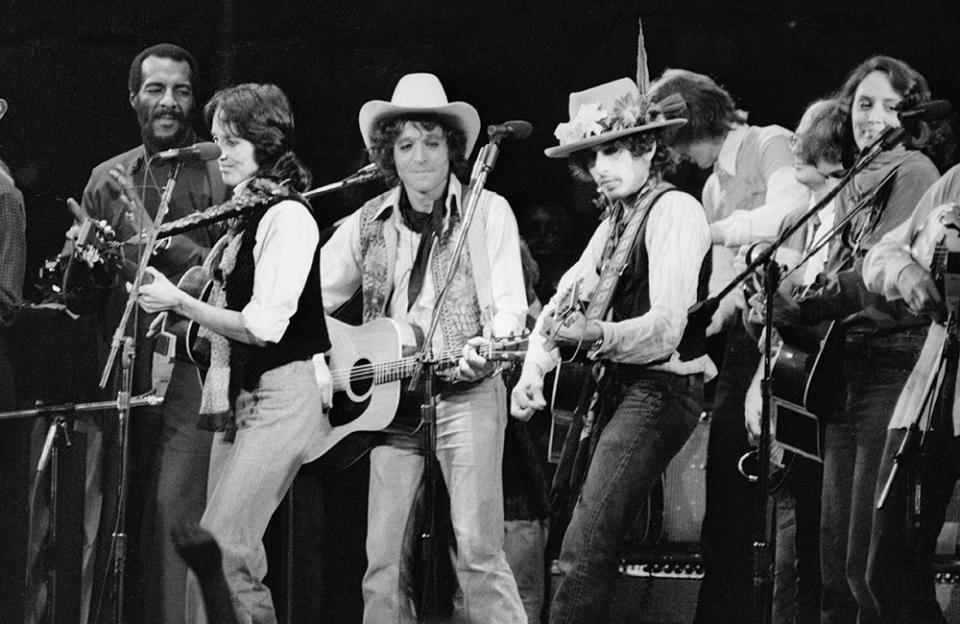

In the fall of 1975, Sam Shepard — the hottest playwright on both sides of the Atlantic — returned to his new home in Northern California one day to find a note waiting for him that said Bob Dylan had called. Having never met him, the 31-year-old Shepard called the phone number on the note and was informed that Dylan wanted him to write the screenplay for the film to be based on his upcoming, star-studded Rolling Thunder tour. Because Shepard, who would later be nominated for an Academy Award for his portrayal of Chuck Yeager, America’s most famous test pilot, in The Right Stuff but was so afraid of flying that he had not been inside a plane for the past twelve years, he crossed the country by rail to meet Dylan in New York. As Robert Greenfield recounts in an exclusive excerpt from his new biography of Shepard, True West, drawing from extensive reporting and the late Shepard’s own writings, the excesses of the tour and the clash of cultures proved too much for him to handle: “Like a pair of large and powerful planets revolving in entirely separate solar systems, Bob Dylan and Sam Sheppard had slowly been gravitating towards each other.” And in retrospect, it seems as though they had always been destined to collide.

Just as he had first done as a nineteen-year-old in 1962, when he went to visit his grandparents in Illinois, Sam Shepard was again crossing America on a train. Now, however, he was, in his words, “On the road to see the ‘Wizard.’” After making his connection in Chicago, he journeyed on until his train finally reached Grand Central Station. Paralyzed by the realization that he was now actually back in New York City, Shepard stayed in his compartment until almost everyone else had left the train.

More from The Hollywood Reporter

How to Watch Bad Bunny, Blink-182 and Blackpink Perform at Coachella 2023

"Good Art, Bad Person": Claire Dederer on the Way Entertainment Is Consumed After #MeToo

After being taken to meet Dylan’s close friend Louie Kemp, who had been put in charge of the tour, Shepard found himself being escorted past multiple levels of security into the Studio Instrument Rentals facility on Thirty-sixth Street off Tenth Avenue. There, he first came in contact with many of those who would also be on the tour, including Allen Ginsberg and as well as Bobby Neuwirth, another of Dylan’s longtime friends, who brought back for Shepard shared memories of nights during the sixties when they had both been part of the scene at Max’s Kansas City.

All this was just a preamble to the evening’s main event, the first meeting between Sam Shepard and Bob Dylan. Like a pair of large and powerful planets revolving in entirely separate solar systems, the two men had slowly been gravitating toward each other since they had first been in such close proximity at the Village Gate in Greenwich Village without ever knowing it, back when Shepard had been working there as a busboy while Dylan was writing some of his greatest songs in sound man and lighting director Chip Monck’s rat-infested apartment right next door.

After being led down a long, dark hallway, Shepard discovered Dylan lying across a metal folding chair in a dark back room with his ragged cowboy boots propped up on a metal desk. Insofar as Shepard could see, Dylan was “blue.” He was “all blue from the eyes clear down through his clothes.” For “about six minutes straight,” as he stared at Dylan, Shepard saw only how he had looked on all the album covers that had been part of the decor in every funky apartment on the Lower East Side of Manhattan and in hippie crash pads all over America for more than a decade.

Having made a gnomic comment about their not having to connect personally, making Shepard wonder if he meant in real life or in the scenes for the movie they were about to shoot, Dylan asked Shepard if he had ever seen Children of Paradise or Shoot the Piano Player. Shepard, who had seen them both, asked Dylan if that was the kind of movie he wanted to make. “Something like that,” Dylan said, before lapsing into a silence so deep and profound that Shepard could hear those words playing back to him over and over again in his head.

Doing his best to fill the void, Shepard mentioned a scene he and the film crew had already begun thinking about shooting with Ramblin’ Jack Elliott in the bathroom of the Gramercy Hotel, where everyone on the tour was staying. Dylan’s face lit up at the mention of Elliott. In the world according to Bob Dylan, Jack Elliott was true royalty. He was the living, breathing connection to Dylan’s great idol Woody Guthrie, who had inspired the former Robert Allen Zimmerman of Hibbing, Minnesota, to begin the journey that would eventually lead to his being awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2016.

Dylan told Shepard that what he needed most now was to get out of the city. Once everyone was on the road, they would be able to really get into this film together.

Having once believed that “the only place to write was on a train,” Shepard had already put the time he had spent traveling cross-country to good use by starting work on the movie he thought Bob Dylan had hired him to write. By the time he arrived in New York City, he had written what the tour’s stage director, Jacques Levy, said were “two scenes for some movie that he had in his head, which he thought Bob would want to do. It was a total misperception. They tried a little bit of work on the two scenes he’d brought—I wasn’t involved . . . and none of it worked out.”

On November 5, 1975, his thirty-second birthday, Shepard found himself sitting in front of three cakes, a giant pen, a studded sex frog, and other assorted goodies in the Red Lion Inn in Stockbridge, Massachusetts. In Springfield, Massachusetts, the next night, he told Rolling Thunder’s press officer Chris O’Dell — who had worked with some of the biggest bands of the 60s and 70s, and with whom the married Shepard would then have an affair while on the tour – that he had no idea what he was doing on the tour. Although Dylan had brought him on to write the script, everything about the film project was so disorganized and chaotic that Shepard confessed he had no idea how to relate to “this rock-and-roll lifestyle.”

Opening himself up to O’Dell, he explained that because nobody ever showed up to film scenes when they were supposed to, they now wanted him to “write the dialogue after it happens.”

Remembering a conversation they had shared a few days earlier, she told him, “But, Sam, you told me you wanted to be a rock-and-roll star.”

“Yeah,” he replied, “but I just wanted to play music. I didn’t want to do this.”

In his 1977 tell-all The Rolling Thunder Logbook, Shepard describes this moment on the tour as “where the film experiment” began “to get interesting. We’ve abandoned the idea of developing a polished screenplay or even a scenario-type shooting script,” as it had become obvious that the musicians, T Bone Burnett, Roger McGuinn, and David Bowie’s lead guitarist Mick Ronson among them, were not about “to be knocking themselves out memorizing lines in their spare time.” Because they were all either “rehearsing all night playing a concert, or jamming, and then crashing out at six or seven in the morning,” it was almost impossible to “even get two or more of them together at the same time in front of the camera.” And so Shepard and the film crew had now “veered into the idea of improvised scenes around loose situations.”

Despite Shepard’s travails insofar as the film was concerned, he and O’Dell were getting on well. As she says, “He was just sweet and gentle and romantic in his own weird way.” O’Dell also saw “another side of him that was pretty weird. When we first started seeing one another, we were pretty quiet about it, but people began finding out all the same. We went to a gig one night and when we came back to the hotel, they had put all my stuff in his room and all his stuff in my room. That really pissed him off, and I had never seen him so angry. They always did these kinds of things on tour as a joke, but it also meant people knew what was going on between us and Sam did not like people fucking with him. That really pissed him off. Why, I don’t know, but it was like his space and his stuff and nobody else should have been there.”

Having repeatedly stated that his real goal in life had always been to become a rock-’n’-roll star, Shepard simply could not tolerate the day-to-day madness of life on the road. “Sam hated it,” O’Dell says. “He hated everything about it. He hated the moving from place to place. He hated that he had to be at a certain place at a certain time, all of that. He was upset and he wanted to leave the tour, because the whole film thing was just kind of a mess.”

On a tour where the pretension had reached brand-new levels after just a few days of working on the film, Lou Kemp called Shepard into “a secret meeting” about what was now needed “to get this film off the ground.” Kemp’s idea was to bring in either Francis Ford Coppola or Orson Welles to take over the project from Shepard.As Kemp told Shepard, “We’re after heavyweights, you understand.”

As always, copious amounts of alcohol helped to sustain the madness. As Ramblin’ Jack Elliott later said, everyone on the Rolling Thunder Revue was pretty much drunk all the time for thirty-one straight days. There was also so much cocaine available on the tour that Joni Mitchell, who had never done the drug before joining the Rolling Thunder Revue, asked to be paid in the substance rather than money, according to Reckless Daughter, David Yaffe’s 2017 book on the singer-songwriter.

Acknowledging the ubiquitous presence of the drug, Allen Ginsberg wrote a four-line poem in which he noted that nobody was going to save America by snorting cocaine, but “when it snows in your nose, you catch cold in your brain.”

Mitchell had flown in from Los Angeles to join the Rolling Thunder Revue in New Haven, Connecticut, on November 13, 1975. After recording six critically acclaimed albums over the past seven years, she was at the height of her career. A groundbreaking artist whose music would only grow in stature over the next five decades, Mitchell was also, much like Bob Dylan, a once-in-a-generation talent.

Despite his relationship with Chris O’Dell, none of Joni Mitchell’s charm was lost on Shepard. In Niagara Falls just two days after Mitchell joined the tour, O’Dell looked everywhere for Shepard after the show but could not find him. At breakfast the next morning, she heard someone say that Shepard had been seen hanging out with Mitchell the night before. When O’Dell saw him later that morning, she ignored him while also noting that he looked guilty. When he did not appear in the hospitality room where he would usually meet her after the show, she decided to take matters into her own hands by knocking on his hotel room door.

After identifying herself, O’Dell waited until Shepard finally came to open the door. In a scene that would not have been out of place on a sitcom, Shepard returned to his bed, laced his hands behind his head, and looked at O’Dell with “a sweet little smile.” When she asked him why he had not come down to the hospitality room, he said he was tired and so had “just been lying around here.”

It was then that O’Dell, who by then had entered his room and was sitting with her back to the door, heard the door open and close. The very picture of innocence, Shepard said, “Oh, what was that?”

Knowing that Joni Mitchell had been hiding in the bathroom all the while and had just sneaked out of the room, O’Dell said, “Sam, who was that?”

“No one,” he answered.

“You know what?” O’Dell told him. “You’re a shit.” And then she went out the door as well.

Unlike almost everyone on the Rolling Thunder Revue, Larry Sloman knew Sam Shepard was an Obie Award–winning playwright. Sloman, who had a master’s degree in deviance and criminology from the University of Wisconsin, had begun his time on the tour reporting for Rolling Stone. Dropping that assignment because “all they wanted to know was how much money Dylan was making from this tour—which, to me, was a great cultural event,” he began an epic struggle to be allowed to remain on the Rolling Thunder Revue so he could write a book about it.

Nicknamed “Ratso” by Joan Baez because she thought he looked like Ratso Rizzo, the character portrayed by Dustin Hoffman in Midnight Cowboy, Sloman first met Shepard in the lobby of the Red Lion Inn in Stockbridge immediately after two burly security guards charged with keeping Sloman away from the principals on the tour had unceremoniously dumped him onto a couch. In Sloman’s words, “Sam was standing by the front desk and I started complaining and he started complaining to me.” On the occasion of his thirty-second birthday, Shepard told Sloman, “I’m pissed off. I’ve been lied to . . . I’m ready to quit, go home. They made some assurances to me in terms of money that they didn’t follow through on.”

As Sloman says, “Sam was a malcontent for the entire tour. He had all those Obies and a name and an ego and then he came on this tour and got slapped around by Dylan, who basically threw out everything Sam had written and said, ‘Let’s just make it all up.’ There was no script for that movie. They were just flying by the seat of their pants and had no idea what they were doing.”

Sloman was with Shepard when the playwright realized he’d finally had enough. The two already had spent and odd night together in Boston when they had both gone backstage to see the Tubes perform in support of their debut album, White Punks on Dope. They then followed backup singer Jane Dornacker, who would later appear with Shepard in The Right Stuff, to a dressing room, where “long lines of snow” were “being inhaled across a record jacket.”

Having already slagged off Prairie Prince, the drummer of the Tubes, for “slashing away at his kit as though he was caught in his own mosquito netting,” in The Rolling Thunder Logbook, Shepard could only wonder, “What are all these kids doing watching this shit when they could be hearing good music?” Expanding on this theme, he thought it was because they wanted “to see some action” and “brains dripping from the ceiling. Is that the generation stuff that you hear about all the time? . . . Am I part of the old folks now? Is Dylan? Could it be that like Frank Sinatra and Bing Crosby, Dylan himself was now actually not known in certain circles?”

And while Sloman would remember the Rolling Thunder tour as “the greatest thing in the world” and “still the highlight of my life,” Shepard felt as though he was “cracking up behind” it while also being transported back to “the mid-sixties when crystal meth was a three-square diet with ‘yellow jackets’ and ‘black beauties’ for chasers.”

Completely losing it in print, Shepard wrote, “I DON’T WANT TO GET BACK TO THE SIXTIES! THE SIXTIES SUCKED DOGS! THE SIXTIES NEVER HAPPENED!” Three days later, in Bangor, Maine, he got into a rental car and left the Rolling Thunder tour by driving to New York City.

On December 8, 1975, the Rolling Thunder tour ended with a sold-out benefit concert for Rubin “Hurricane” Carter, the wrongfully convicted boxer that inspired Dylan’s epic song “Hurricane”, before fourteen thousand people in Madison Square Garden. Joining the pantheon of stars who had performed thirty shows over the past forty days were Muhammad Ali, Coretta Scott King, Robbie Robertson, and Roberta Flack. The dramatic nature of the final concert notwithstanding, Shepard himself had other things on his mind. In four days, Geography of a Horse Dreamer, a play no one in New York City had seen which Shepard had written and had been first performed in London with Bob Hoskins and Stephen Rea in the cast, was set to open at the Manhattan Theatre Club, a ninety-seat venue then located on East Seventy-third Street between First and Second avenues.

Adding to the pressure of having every major newspaper critic in the city review Shepard’s play, Bob Dylan and his wife, Sara, had told Shepard they wanted to see the show. He then invited them to the first performance only to learn that it would also be a preview for the press. As he writes in The Rolling Thunder Logbook, “Great, an audience full of critics and Bob Dylan. Couldn’t be worse.”

Despite his multiple responsibilities on the tour, Jacques Levy had chosen to leave it so he could spend two weeks directing rehearsals for Geography of a Horse Dreamer, which Shepard also attended. On the play’s opening night, Levy was also willing to hold the curtain until Dylan, whom Shepard later described as being “plastered,” finally arrived with Sara, Bobby Neuwirth, Louie Kemp, and another of his people in tow.

From his place at the back of the theater, Shepard knew his play was dying on its feet by the deafening sound of silence in the house. As he stood there “cringing in the dark,” he could only ask himself why, of all his plays, Dylan had chosen to come to this one rather than those with music or dialogue that would have made the audience laugh.

Unable to take any more, Shepard headed out a back door and was about to leave the theater when Levy came toward him. Offering him the joint in his hand, the director said, “Here’s something for the pain, Sam.” Availing himself of the offer, Shepard took a heavy hit and then realized that he had no choice but to steel himself for the agony of watching what he had written in private be transformed into a public event in the most painful way imaginable.

Stoned out of his mind, he made a beeline for the bar during the act break only to quickly turn around and head back up the stairs when he saw the size of the crowd there. As bad as it had all been for him until now, Shepard took comfort in thinking Dylan had walked out on the show and so would not be around for the second act.

Without warning, Dylan then suddenly emerged from the men’s room. Stuffing a bottle of brandy into his pocket, he began fumbling with the notes he had scribbled during the first act. Spying Shepard, Dylan asked him how the play ended. He also wondered why one of the greyhounds in the play was named “Sara D.,” having taken this as a reference to his wife.

Less than halfway into the second act, Shepard saw that two of the most important newspaper critics in the city were now fast asleep. At the point in the play when Cody was about to be injected with a syringe so his “dreamer bone” could be removed, Dylan suddenly jumped to his feet and shouted, “Wait a minute! . . . Wait a second! Why’s he get the shot? He shouldn’t get the shot! The other guy should get it! Give it to the other guy!”

As Louie Kemp began hauling Dylan back into his seat and Neuwirth told him over and over to shut up, the critics down front suddenly came back to life. When Cody’s two cowboy brothers entered the scene, Dylan leaped to his feet again and shouted, “I DON’T HAVE TO WATCH THIS! I DIDN’T COME HERE TO WATCH THIS!” Fighting to escape Kemp’s “hammer-lock grip” as Neuwirth and others tried pulling him back down again, Bob Dylan simply would not be denied. All the while, he kept insisting, “HE’S NOT SUPPOSED TO GET THE SHOT! THE OTHER GUY’S SUPPOSED TO GET IT!” As soon as the play ended, Dylan was out the door and gone.

From the book TRUE WEST: Sam Shepard’s Life, Work, and Times by Robert Greenfield. Copyright © 2023 by Robert Greenfield. Published by Crown, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

Best of The Hollywood Reporter

'The Super Mario Bros. Movie': See Who Voices the Beloved Characters

Hollywood Reporter Critics Pick the 50 Best Films of the 21st Century (So Far)

Hollywood Flashback: 'Soylent Green' Depicted an Overpopulated Planet With a Dark Secret