‘Salvatore: Shoemaker of Dreams’ Review: Luca Guadagnino Lovingly Lionizes Ferragamo

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

“Salvatore: Shoemaker of Dreams,” Luca Guadagnino’s winning documentary delving into the life and career of legendary Italian shoe designer Salvatore Ferragamo, begins appropriately enough with a pair of high-heeled ruby slippers in the process of creation. The sparkling red objects pass through various checkpoints and construction moments in a seamless integration of people and machines, wearable art both handmade and mass-produced.

These opening shots, satisfying and methodical — presented without explanation, suggesting that Guadagnino might be assuming a fly-on-the-wall approach for the duration — quickly give way to traditional documentary practices, and pleasingly so. This is history not widely known outside the world of fashion, and Ferragamo’s story is a complex intersection, touching on early-20th-century immigration, youthful ambition, the dawn of Hollywood, passionate artistic hunger, tenacity, foot fascination and wild innovation. Thus Guadagnino’s carefully and lovingly detailed history lesson, free of stylistic flourishes, is as satisfying and methodical as that red shoe–making.

This early nod to “The Wizard of Oz” is appropriate, too, as Ferragamo’s trajectory encompasses both the groundbreaking, rainbow-patterned, cork-heeled platform sandal he designed in 1938, reportedly for Judy Garland herself, and a teenage uprooting that not so faintly resembles that of the fictional Dorothy Gale, the smalltown girl dropped into an alien Technicolor environment.

Also Read:

Luca Guadagnino’s Fashion Doc ‘Salvatore: Shoemaker of Dreams’ Acquired by Sony Pictures Classics

Born in 1898 to a farm family of 14 children in the village of Bonito, Italy, Ferragamo was fascinated by the neighborhood cobbler and spent hours watching and learning until, as a 9-year-old, he made his first shoes for his sisters’ Communion. Then he left home, determined to study shoemaking in Naples. Which he did. At age 10.

Then he returned home to Bonito to open his own shop. He was 12.

By 1915, aged 17, the prodigy was on a ship to the United States, where he promptly turned up his nose at the mass production of shoes he witnessed on the east coast (describing them as “brutal” and “clumsy” in voiceover narration from Michael Stuhlbarg). He boarded a train to California and settled in Santa Barbara, free there to make shoes however he pleased. This led to work on silent-movie sets, producing shoes for films, enrollment at University of Southern California to study human anatomy in order to make his shoes’ arches more comfortable, and then to craft custom footwear for silent film stars like Lillian Gish and Mary Pickford, and later for Joan Crawford, Bette Davis and every other woman in the movies.

Guadagnino understands Ferragamo’s life as one woven into the birth of Hollywood as a film empire, and for the way in which his shoes, marked with a name that came to stand for luxury and innovation — what costume designer Deborah Nadoolman Landis refers to, in interview, as “audacious footwear” — marched alongside the ascendance of movie stars as a form of American royalty.

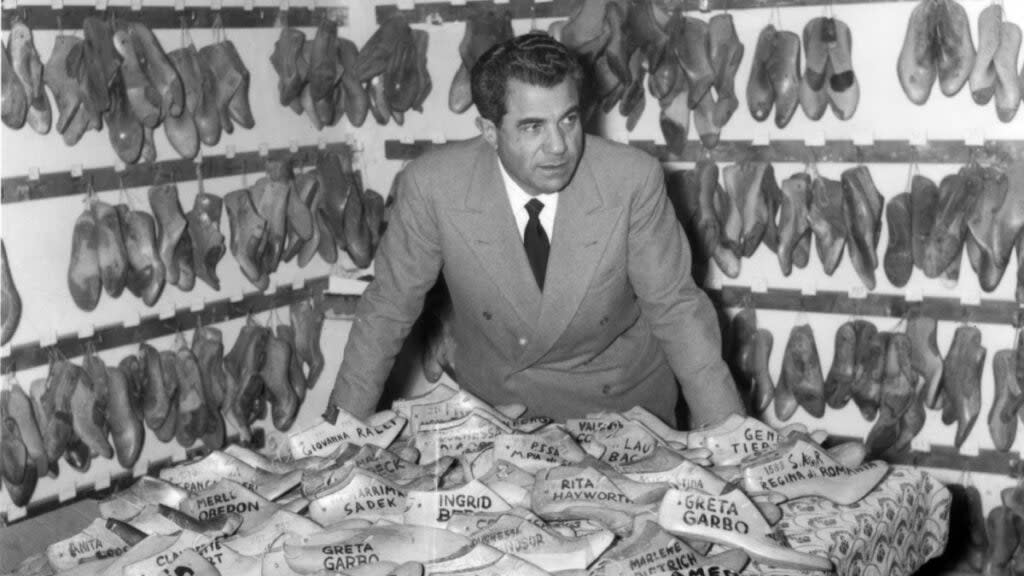

Guadagnino assembles a sweep of archival materials and a robust roster of interviewees, among them fashion editor Grace Coddington, director Martin Scorsese and contemporary fashion stars like Christian Louboutin and Manolo Blahnik (the latter the subject of the documentary “Manolo: The Boy Who Made Shoes for Lizards”), a chorus of praise for Ferragamo’s inventive nature, his strategic business mind, his refusal to succumb to “the temptation of the assembly line” after returning to Italy in 1926 and his determination not to fail even in the face of bankruptcy and Mussolini’s fascist government.

Risking hagiography, Guadagnino spends a significant portion of the film’s later moments recounting the designer’s warm family life, which includes glowing testimonials from Ferragamo’s own children and grandchildren, many of them still involved in the family business, and none of whom have anything to say that would counter Ferragamo’s wife Wanda’s loving accolade, that he was “as good as bread.” She adds, slyly, “… hard bread.”

Also Read:

‘Manolo’ Review: Shoe Maestro Blahnik Gets Effusive, Adulatory Doc Treatment

And that’s as big a hint as the film is willing to give that Ferragamo was ever mean or depressed or unkind like every other human being who’s ever lived. If he suffered internally, in ways similar to other famous subjects of other fashion documentaries — Halston, Alexander McQueen, Yves Saint Laurent — it’s not this film’s desire to explore it.

This is a full tribute, not “House of Gucci,” and it’s one that focuses on the best of the man, letting the legend remain legendary, culminating in a delightful animated shoe ballet and those ruby slippers clicking away. At one point, Scorsese paraphrases Bob Dylan’s assertion that the self is not found but created, and it would seem to fit here like a good shoe. Ferragamo arrived in Oz, studied it in detail, built his own road and turned himself into the wizard.

“Salvatore: Shoemaker of Dreams” opens in US theaters Nov. 4 via Sony Pictures Classics.