The sad, shocking story behind the Jonestown massacre, 40 years later

Some tragedies lose their power to shock with the passage of time. That’s not true of what’s become known as the Jonestown massacre. Forty years ago, on Nov. 18, 1978, self-styled holy man Jim Jones oversaw the mass slaughter of nearly 900 members of his church or, more accurately, cult — the Peoples Temple, marking the terrifying end to their experiment in building a utopian community in the South American jungle. One reason why the horror of that event hasn’t faded four decades later is because Jones recorded himself preaching to his congregation as they died, entreating them to drink poison and ensuring that the colony’s large population of children consumed it as well.

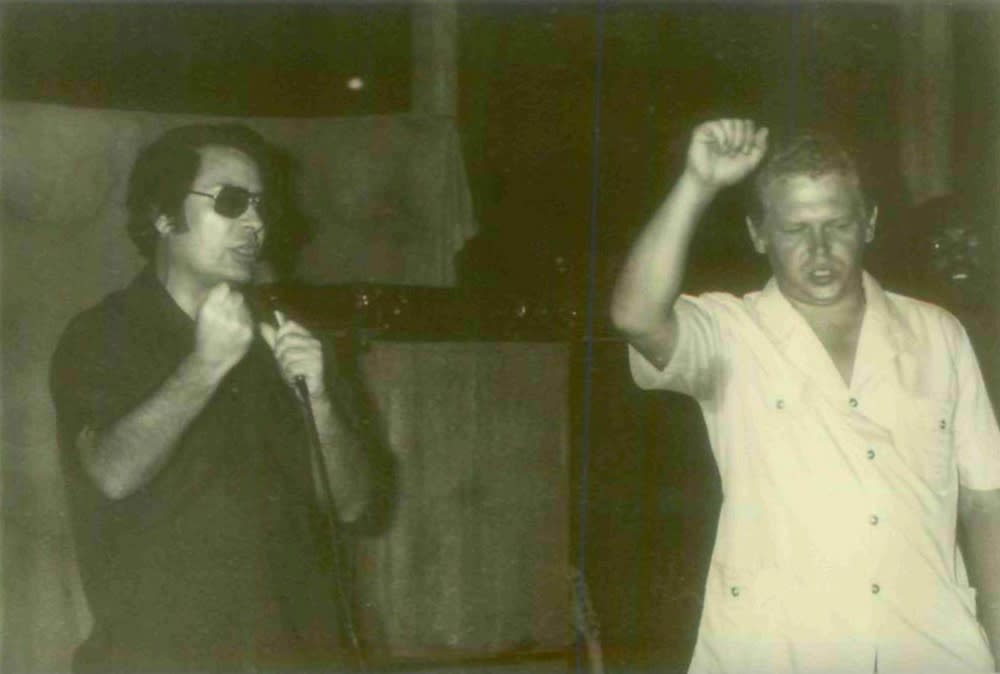

Flash-forward to the present day, and Jonestown has become the go-to example when both professional and armchair analysts discuss the madness of crowds, or single-minded devotion to a religious or political leader. At the same time, the emphasis on the massacre often overwhelms the story behind Jonestown and Jones himself. The new four-part documentary series Jonestown: Terror in the Jungle, which premieres this Saturday on SundanceTV, reconstructs the incident’s history through the testimony of Jonestown survivors, Jones’s now-grown sons and author Jeff Guinn, who wrote the 2017 book The Road to Jonestown.

Speaking with Yahoo Entertainment, Guinn expressed some regret that the Jonestown massacre has become such a ubiquitous reference point, inspiring such oft-heard phrases as, “Don’t drink the Kool-Aid.” “First of all, it wasn’t Kool-Aid,” he notes. “And second, let’s face what the connotation is; it’s used to mean, ‘Don’t be a mindless zombie who just automatically follows orders from an obviously demented leader.’ And the situation in Jonestown wasn’t like that at all.” We spoke with Guinn about the details that are often left out when Jonestown is discussed, and what parallels he sees between Jim Jones and a leader like Donald Trump.

Yahoo Entertainment: Forty years later, what are the biggest misperceptions people have of Jonestown and how do you hope to correct them with your book and the documentary?

Jeff Guinn: Like everybody else, when I started writing the book, I didn’t know there were misconceptions. There were three huge surprises for me during the more than three years I spent researching. The first one involved Jim Jones. I had no idea that he had been such a great leader in the American civil rights movement. He and his wife almost singlehandedly ended total racial discrimination in Indianapolis, which was one of the most segregated major cities in America. There’s always an element of fraud there; he would do all these miracle cures to attract audiences, and they weren’t miracle cures. But he accomplished all these good things that I’d had absolutely no idea about until I got to Indianapolis.

The second thing was that the quality of the people who joined Jim Jones and became members of Peoples Temple included some of the most intelligent, talented and socially committed people you’d find anywhere. These weren’t dummies just falling into place; they really believed in what Jones was preaching. And the third thing is that the mental image most people have of what happened that day, 40 years ago, is that you had almost 900 people in line obediently drinking these cups of poison and falling over dead. A few did that, that’s true — but over 300 of the people who died that day were infants and toddlers who had no choice. And based on autopsies and studies done by the Guyanese doctors on site right afterward, many of the people involved had abscesses on their bodies. They hadn’t taken the poison voluntarily; there were armed guards all around the pavilion in Jonestown, and people who dissented were held down and forcibly injected. So we’re talking mass murder as much or more so than mass suicide.

While you were researching and writing, would you try to put yourself in their place? Did you think about whether you would have been susceptible to Jones’s message in the first place, and then what you would have done on the day of the massacre?

When Peoples Temple was in its heyday, I was a teenager growing up in Texas and I was very socially active. I was very much antagonized by racism, particularly the way Hispanics were being treated in Texas, and I tried to get involved politically as much as I could. But in those days, an 18- or 19-year old kid didn’t get to vote, and there wasn’t that much you could do. So if Jim Jones had suddenly shown up in Austin, Texas, with the Peoples Temple, I would’ve felt so caught up by not just the promises of, “If you join us, you will be able to make a difference.” The actual proof [was there]; if you joined Peoples Temple, you really did get to make the world a better place in some way or another. I could see myself climbing on the bus and going with them.

Frankly, I don’t see that I would’ve stayed to the end, as Jones got increasingly bizarre in his behavior. Then again, talking to the folks who did join, they hasten to point out that Jones didn’t go over the edge just all of a sudden one day. It was a very gradual process. One survivor, Tim Carter, again, said it was like the frog in a pot of water. If you drop a frog in a pot of boiling water, it’ll try to hop out right away. But if you put the frog in lukewarm water and warm it up a degree at a time, it’ll stay there, not realizing it’s being boiled alive.

That speaks to the idealism and commitment of the people Jones attracted that you referenced earlier.

One of the things that pleases me so much about the documentary is that it shows how the members of the Peoples Temple would still be able to do things — from free clothing and food to those in need to marriage counseling — even with all the crazy things going on amongst the leadership. There are people walking this earth who will tell you they wouldn’t be alive without Peoples Temple. So every day, they could feel that they were doing something worthwhile, that they dedicated their lives to a great cause, not realizing that the leader at a certain point was going to decide that the final grand gesture would be what he called a “revolutionary act” glorifying suicide and mass murder.

We’ve frequently heard the term “cult” frequently applied to Donald Trump and his followers. Leaving aside how Jim Jones’s story ended, do you see any parallels to what we’re seeing play out today?

All politicians and all religious leaders to a certain extent have to be demagogues. They’re trying to create a sense of urgency: You’ve gotta vote for me, you’ve gotta come to my church. Jones had characteristics that every demagogue has in common. The most obvious ones are they identify current social problems, but they exaggerate the danger. They want to make people feel scared; they always present themselves as the only one who can solve the problem; and they do their best to convince their followers that anyone who disagrees is the enemy. And the last thing is they try to cut them off from other opinions and voices. They will always first attack the media, then they will try to separate people even from family and friends. They don’t want any dissenting voices at all, and they’ll do whatever they can to keep the outside world away from their followers — to keep reality away from their followers. Those are the qualities of the worst demagogues. Jim Jones fits that to a T, and I think people need to ask themselves: Is there a lesson here for the present day?

It’s interesting that that Jones’s views were very progressive in some ways, whereas Trump’s ideas about improving the country are about taking it back to a vanished past.

See, that is the difference. That’s the thing that makes Jones unique among successful demagogues who ultimately led their followers into disaster. He’s been compared the years to Hitler, but unlike Hitler, Jones didn’t gain his followers by appealing to their worst natures. Jones told his followers, “You’re gonna have to give up things. What we’re trying to do is make sure everyone gets a fair share, not that you’re going to get more.” No one ever got anything from becoming part of Peoples Temple — they had to give. And that’s what makes Jones all the more frightening, because we always figured that the demagogues who are going to lead people into terrible ends will say God-awful things. Jones did it the other way, and it was extremely effective.

You’ve been to the remains of Jonestown: Looking at it now, do you see any way in which it could have become the utopia Jones promised?

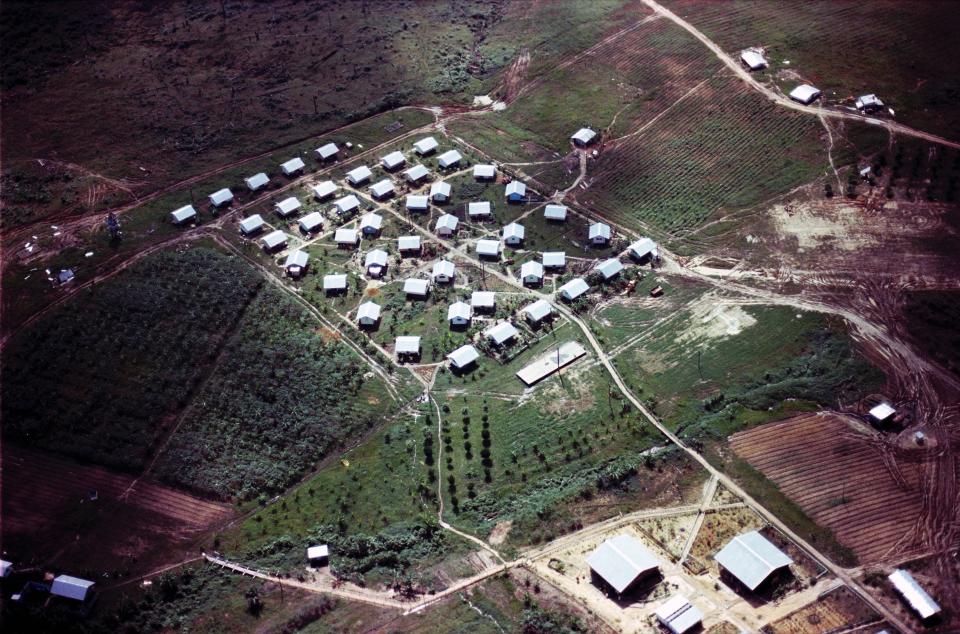

The thing that a lot of people miss is that Jonestown wasn’t intended to be the main base of Jones’s remaining following. It was supposed to be a small overseas outpost, where the Peoples Temple was going to establish a working farm. When Jones fled the U.S. after those great investigative articles about him destroyed his political and public base, he brought with him almost a thousand people. So from the beginning, there’s overcrowding. They’re never gonna be able to grow enough food to feed themselves, and there’s constant physical labor without nourishment.

Meanwhile, Jones is in the grip of drugs more than ever, and his paranoia is expanding. But there they are 150 miles away from anything, and the only voice they hear every night is Jones telling them news from America, that concentration camps for blacks have just been opened, that the Army is now shooting down even more dissidents just like us. So you’ve got exhausted people who are malnourished, and they’re hearing this over and over from Jones.

Standing in Jonestown, did you feel the ghosts of what happened there decades ago?

I felt stunned. Until I had gone through that jungle, I had no idea just how wild and primitive and frightening it truly was. It’s triple-canopy trees so close together the sun can hardly break through, and brush with all kinds of thorns that tear at your clothes and your skin. You can hear rustling from animals nearby, but you can’t see them and you have no idea what there are. Snakes are everywhere, as well as bugs of every kind, most of them swarming and biting you. And then finally you make your way with tremendous difficulty to what’s left of the clearing that Jonestown cut, you realize the immensity of what those people accomplished. So I stood there, and that’s when I finally understood what it must have taken to build Jonestown at all. If Jones hadn’t gone there, it’s very likely that all these years since, there would still be a working farm and settlement called Jonestown.

Out of all the stories you heard while reconstructing the events of Nov. 18, what’s the account that still haunts you?

To me, the most shattering experience was the time I spent with Tim Carter, who survived that day from Jonestown, and lost his wife and son at the same time. Sitting in his apartment and hearing him talk about that day, I felt his tremendous sense of loss. And I couldn’t be more impressed by the courage that survivors have shown by being willing to open up and be so honest for this documentary. I would never have been able to do that, and my admiration for them is just immense.

There’s an undeniable fascination with the ghoulish aspects of the Jonestown story. Are you bothered by the way it’s become a pop culture touchstone, as opposed to a historical tragedy?

When I was in Guyana, a group of travel agencies from around the world had come to Guyana to explore the possibilities of making the Jonestown site a [tourist] “destination.” They talked about how there are all these tourists who “love” — and this is their term — death tours. That they love going to the concentration camps in Germany and imagining the horror there. And they thought that if Jonestown was somehow reconstructed, that people would want to come, and you could sell them punch, and they could line up and pretend to be poisoned and die. So of course, there’s a portion of the public that’s always going to be attracted to that. But I also think that most people essentially are warmhearted, and if they’re given the opportunity to understand, they can sympathize. This show provides the evidence to get the full understanding of what happened, and not the cartoonish, one-dimensional idea most of us had for 40 years.

Jonestown: Terror in the Jungle premieres Nov. 17 at 9 p.m. on SundanceTV.

Read more from Yahoo Entertainment: