The Rolling Stone 250 greatest guitarists list gets a lot of things right – but some of its exclusions are just plain wrong

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Rolling Stone released its countdown of the 250 Greatest Guitarists of all Time last week – its first update on the chart since its 2011 top 100 list – and to say it’s caused uproar among guitarists is something of an understatement.

There are a lot of talking points in there, particularly for anyone used to the old ‘stale, pale and male’ lists of yore: Eric Clapton is number 35, Slash doesn’t even get a look-in at the top 100 and there are more than a few inclusions that feel like afterthoughts.

Putting these lists together – and we’ve done a few – is always an imperfect science, to say the least. Public votes are distorted by social media campaigns, while ‘panels’ and debates are subject to the personal blindspots of the tastemakers involved.

‘Of all time’ never actually means ‘of all time’. Rolling Stone has, sadly, not unearthed your new favorite 12th century North African shredder. Instead, it is always more accurately described as ‘of its time’.

A list like this will always tell us more about where we are today, against our current biases, collective memory and cultural obsessions – than about the past it attempts to bottle.

Done well, then, they should create a conversation, create a debate as we come to terms with the change – and, eventually, move the cultural discourse a little further down the road. In that spirit, then...

For me, many of the calls that have led to the uproar are absolutely justified. Much of the chart looks out of whack because that’s exactly what should happen when you start shining a light on the whole of guitar-based popular music, rather than a limited selection of white, male blues rock revivalists.

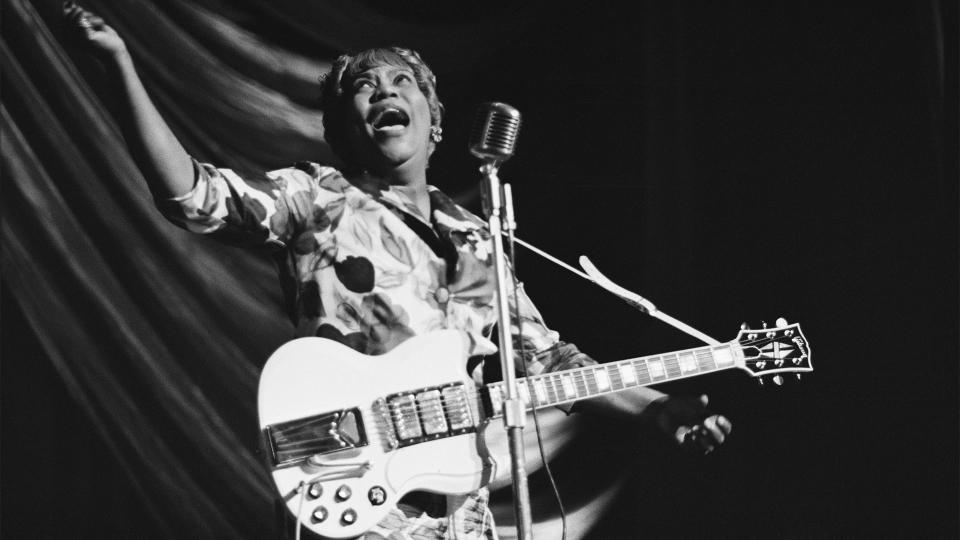

In this context, it’s only fair to place the mighty Sister Rosetta Tharpe at number six, comfortably ahead of some of the players she inspired, like Keith Richards (15), or the aforementioned Clapton.

However, that sort of central logic seems, at best, applied at random on the rest of the list. It’s a big list, too – running to a mammoth 250 players – and, of course, the longer the list, the more you open yourself to criticism when something is missed. And there is plenty missing.

There’s no room in the top 250 for djent pioneer Misha Mansoor, who has played a seismic role in reshaping metal over the last decade

The magazine lists its criteria as valuing “heaviness over tastiness, feel over polish, invention over refinement, risk-takers and originators more than technicians” and having a bias to players who made “great songs and game-changing albums, not just impressive playing.”

It also draws a line in the sand on the instruments included: “Our only instrumental criteria is that you had to be a six-string player”.

The latter point is a figure of speech, we suspect, given they include Tosin Abasi in the lineup, but it’s a bit clumsy, given that a significant chunk of the “risk-takers” and “originators” of the last decade of guitar music have used seven-string and eight-string instruments.

On the heavier end of the spectrum, Rolling Stone, like much of the legacy rock press, has traditionally held its nose when it comes to covering metal.

Here, it goes some way to correcting that bias, giving Tony Iommi the number 14 spot, while Meshuggah’s Fredrik Thordendal comes in at 141 and the aforementioned Abasi places at 99 – there are also nods to Judas Priest and Maiden’s iconic pairings.

But there’s no room in the top 250 for djent pioneer Misha Mansoor – who has played a seismic role in reshaping metal over the last decade – or Mastodon (who took metal to the Grammys), or even bonafide thrash legend Dave Mustaine. Or prog-metal pioneer John Petrucci.

Relatedly, the shred movement (bar the obvious: EVH, Satch and Vai) is basically ignored. There’s no Yngwie Malmsteen or Jason Becker. No Marty Friedman.

We get they may not all be household names, but there are players on the list that are not, and who have taken fewer risks – try electrifying Bach in the MTV-era and let us know how you get on, eh? – or done little to ‘change the game’.

There’s no Yngwie Malmsteen... try electrifying Bach in the MTV-era and let us know how you get on, eh?

In contrast, those Shrapnel Records shred players shaped the way we play guitar and think about its possibilities in 2023 – whether you like the sound, or not.

Even areas where you’d expect Rolling Stone to show a little more nous are lacking: Boris’ Wata gets a nod, but influential noise rock gods like Earth’s Dylan Carlson, or Melvins’ Buzz Osbourne are notably absent.

John McGeogh, Marc Ribot and Kevin Shields are welcome inclusions when it comes to rock and indie’s tonal experimentalists, but then Cocteau Twins’ Robin Guthrie is left in the dark.

Guthrie invented the dreamy sound that has powered much of the genre over the last 30 years, from the first shoegazers, to Beach House and Grimes. Listen to tones and the animalistic solo on Musette and Drums and tell me that's not an inventive ‘feel’ player.

You could accuse Rolling Stone’s list of recency bias, but then there’s no Steve Lacy, or Adrienne Lenker. Lucy Dacus gets an early shoutout, yet there’s no room for Phoebe Bridgers, who has been hugely influential in encouraging new guitarists to pick it up, or Julien Baker (arguably the finest fretter of the boygenius triple threat).

Then there are a host of other players from ‘our world’ that might not bother the likes of Rolling Stone normally. Surely in this circumstance, though, one or two might warrant a mention?

I mean the likes of Tommy Emmanuel, Martin Simpson and Al Di Meola on the acoustic side. Joe Bonamassa, Guthrie Govan, Lari Basilio, Nili Brosh, Orianthi, Robin Trower, Eric Gales and Robben Ford, on the electric guitar side. Even those with one foot in the mainstream camp – we’re talking big-name players like Neal Schon and Gary Moore – are left out.

They may not make music to your personal taste, but it should be possible to set that aside and respect that they have pushed the envelope.

And then there are the plain oversights: George Benson is conspicuously absent. He started making records aged 10, cut his teeth with Miles Davis, went triple platinum with 1976’s Breezin’ and is, without argument, one of the all-time jazz guitar greats… but there is no room in the 250 for him.

The same can be said of Allan Holdsworth. The British fusion/prog icon influenced many of the highest-ranking names on Rolling Stone’s list – among them Eddie Van Halen, Tom Morello, Vernon Reid, Frank Zappa and John Frusciante – and was named by Vai as the ‘best guitar player’ (should such a thing exist), but does not warrant a mention here. (And Reid is not impressed...)

Jack White gets number 32, yet Dan Auerbach is nowhere to be seen. These are two players that have things in common but are no way interchangeable.

Both have created their own sound, ‘changed the game’ when it comes to post-2000s guitar music – and have had their own influential roles in inspiring new players and in championing underrated talent. However, while one is placed higher than Eric Clapton, the other is not mentioned at all.

If we’re really talking about prioritizing “great songs and game-changing albums, not just impressive playing” then surely, the session greats have to get a look in?

[As an example of that influence, Bombino makes the list. He’s a remarkable guitarist and was first mentioned on Rolling Stone’s site in 2012, following an interview with his producer… Dan Auerbach.]

Then there’s the group I would call the ‘traditionally underrated’. Those who have been left out in the cold by music history, because they played for a union day rate and didn’t get their picture taken for the cover.

If we’re really talking about prioritizing “great songs and game-changing albums, not just impressive playing”, then surely, the session greats have to get a look in?

The 'Wrecking Crew' regulars, included Tommy Tedesco, Carol Kaye, Billy Strange, Barney Kessel and Glenn Campbell. Between them, they played on everything from Jimmy Webb’s Wichita Lineman, a massive chunk of the Beach Boys’ catalog (including that darling of the music press, Pet Sounds) and music by The Righteous Brothers, The Everly Brothers, The Mamas And The Papas and, not forgetting, Phil Spector’s Wall of Sound productions.

Then there’s the Detroit players, i.e. Motown’s rotating ‘Funk Brothers’ line-up, including Robert White, Eddie Willis, and Joe Messina. Without them we’d have no My Girl riff, no pulsating guitar on You Keep Me Hanging On, no What’s Going On?

Indeed, without The Wrecking Crew and the Funk Brothers, we’d have been denied the vast majority of ’60s and ’70s most iconic pop, soul and funk music – often regarded as the highpoint of American pop culture. The stuff that fills out the upper echelons of Rolling Stone’s 500 Greatest Songs of all Time list.

Documentaries, YouTube interviews and wider public interest has helped to share the stories of these crucial players in recent years. The balance has begun to get redressed, but there’s not even a collective nod or footnote on Rolling Stone’s list.

Rolling Stone’s last guitarist list, published in 2011, spoke to musicians (“mostly older classic rockers”) to determine its selections. This time it put the list together from its staff. But that might be the issue.

They absolutely don’t need to ask the same old rockers again, but it might have been good to talk to more players, albeit a much more diverse selection than they did a decade back.

I called it an imperfect science earlier, but maybe it’s more of an artform. And, like all art, you need to have something to say. Rolling Stone’s list justly redresses the established order in a few, seemingly random, places. After that, I’m not sure what it is saying – and, neither, it seems, is Rolling Stone.