Roland Emmerich, Master of Disaster, Returns to Big-Screen Cataclysms With ‘Moonfall’

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

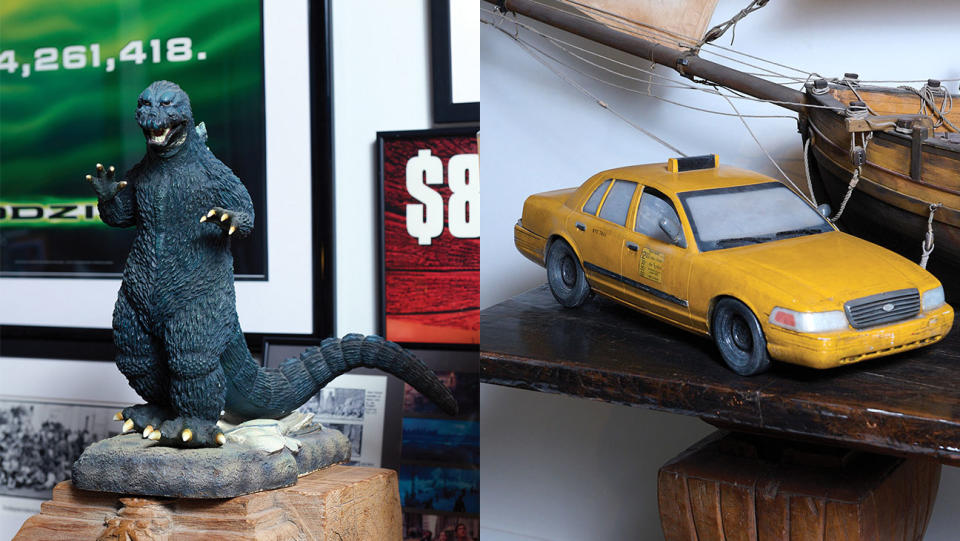

In order to create, filmmaker Roland Emmerich surrounds himself with memories of destruction. The Hollywood office of his Centropolis Entertainment features mementos from his catastrophe films Independence Day, The Day After Tomorrow and 2012. Though he’s known as a master of disaster, his office also is a testament to his projects outside the genre (see: Stonewall, Midway and The Patriot). “They would love me to make the same movie over and over again,” Emmerich says of his agents and Hollywood in general. “I always say, ‘I have to find a new way to do it.’ You cannot, every two years, put some disaster movie out there.”

This time, he waited five years. The German filmmaker returns to world-ending with Moonfall, his first sci-fi flick since 2016’s Independence Day: Resurgence, starring Halle Berry, Patrick Wilson and John Bradley as a trio tasked with preventing the moon from crashing into Earth.

More from The Hollywood Reporter

Sky Deutschland Secures 'Moonfall,' 'The 355' in Licensing Deal With Germany's Leonine

Nicole Byer, Career on the Rise, Slides Down a Stripper Pole

Emmerich, 66, wanted to make the project for years, initially selling the concept to Universal, where it languished for a few years. When he regained the rights, Emmerich took it to Cannes and raised enough capital to make the $138 million film independently — a move that allowed him enormous creative control and gave him a 50 percent stake. (Lionsgate will release the film domestically Feb. 4.)

Speaking with THR, Emmerich weighs in on the possibility of a few sequels, shares his thoughts on Adam McKay’s disaster pic Don’t Look Up and reveals hopes for more intimate films — including a Marilyn Monroe movie.

It’s nearly unheard of for a director to raise this much capital for a feature. What was your pitch to financiers?

These kinds of movies never get offered in Cannes. It’s a tall task. Scanline [VFX] helped us do this one-shot trailer, which was really cool. We had no cast, so then Harald [Kloser, writer-producer] and I kind of sat on these two chairs [and took questions] in front of all the buyers. This was a full room, trust me. (Laughs.)

You and Dean Devlin were planning an asteroid-destroys-Earth movie after Independence Day. Instead, you made Godzilla, and by that time, Armageddon and Deep Impact came out. Is this closure?

I didn’t want to do Godzilla. But they made me a deal, which was unheard of. I said, “OK, let’s go about this really radically. I’m not doing big-belly Godzilla. I’m doing him as a lizard.” That was supposed to tell everybody I can’t do this movie. [Godzilla owner Toho] said, “Oh, we’ll call this the new Godzilla, the Hollywood Godzilla. Then, we can still do our fat Godzilla.” [Toho continued to make Godzilla movies with its classic look, while Emmerich’s Godzilla was leaner and faster.] I said, “Shit!” I was constantly working on my meteor film. It just got swept away by Godzilla, and then all of a sudden, Michael Bay came along and did it first.

You’ve seen filmmaking change a lot. Do you miss the days when special effects were more constrained?

I’m torn. It was a fun time shooting with models. Sometimes, they look better. For [the 2008 movie] 10,000 B.C., they built the biggest model set ever. Then we [added] the people and the smoke and the animals and it was just like magic. That was, for me, the best combination of models with digital enhancement.

Photographed by Yasara Gunawardena

At one point, you said 10,000 B.C. would be the last movie you would ever direct. Why did you feel that way?

It was the most grueling shoot. We wanted to shoot the whole movie in Africa, but they didn’t allow us to do certain helicopter scenes. Then, we had to go to New Zealand. They said, “In May, snow doesn’t stay,” but there was a half a meter of snow. I was supposed to shoot this movie in 82 days and we went over by 20. That’s why I said, “Early retirement!”

When you do a drama like Anonymous or Stonewall, what is the reaction from your agents when you say you want to do something smaller?

They don’t like that. “Why do you want to do that?” They are super critical that I am now doing everything myself [outside the studio system]. My normal salary had to be reduced to make these movies possible. I have enough money. It’s not the money anymore. (Laughs.)

Did you consider selling Moonfall to a streaming service?

No. I own 50 percent of this film. So that means if it makes money, then 50 percent is mine. Then I have to pay Harald and all these other people. But a big piece of it is mine. Yeah, you never know with movies. It could die at the box office or be a huge hit or make barely its money [back]. Who knows these days.

Photographed by Yasara Gunawardena

The Day After Tomorrow was the first global warming-themed blockbuster I can think of. Seventeen years later, Don’t Look Up is a hit, or so says Netflix. Do you think films like that help change the audience’s minds?

The Day After Tomorrow was ahead of its time, and I’m a little bit worried that Don’t Look Up will not do anything. You have to really, really frighten people. And at the end [of Don’t Look Up] it’s like … they all sit there and eat and that’s it. And then, a very comedic scene with Meryl Streep. I didn’t care too much about it, with all the big actors and everything. Naw.

I suspect you have no interest in superhero movies, but were you offered them over the years?

I never had any relationship to it. I got them offered right and left, but I never said yes to any one of them. It’s just not my thing.

You write a lot. How many scripts do you have in the drawer that you’d love to make?

Three. One is a mistaken identity movie where a young writer has to take over a whole film set around 1919, something that I have always wanted [to make]. I have this story of the only good conquistador. And a movie called Happy Birthday, Mr. President, which takes place in the ’60s that’s about the death of Marilyn Monroe.

Photographed by Yasara Gunawardena

You almost never do sequels, but the end of Moonfall clearly sets up the possibility for more. Could you see yourself making another one?

I don’t have to. If it’s an enormous, enormous success, why not? What I will then do, is do two and three together. And have a real, clear cliffhanger [in between].

A decade ago, you were talking about Lawrence of Arabia for television. How intriguing is TV for you?

I am still working on that project. I found a new writer. I think he’s clearly better. He is English, but he lives here in Los Angeles. We are working through the 10 episodes we want to do.

Photographed by Yasara Gunawardena

You don’t like studio notes. But can you recall one that was helpful?

(Shakes his head no.) Most of the time, you know yourself. [In a test screening], you immediately get where the problems are and then you work on them. Certain problems you can never erase. But if it’s a good script, every actor is essential. You have to cut them as tight as you can and hope for the best.

What is your schedule like when you are at home? How do you balance everything?

It’s easy. Honest to God, most of the time I’m bored. I get stressed maybe four weeks before I start shooting, because then it’s building up. When I shoot, I love to shoot. That’s good. Then I go very intensely into the editing room after a break. After four weeks, I have my movie.

Photographed by Yasara Gunawardena

Interview edited for length and clarity.

This story first appeared in the Jan. 26 issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine. Click here to subscribe.