Roger Corman, master of cheap and cheesy film-making who promoted gifted new directors – obituary

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Roger Corman, the film producer and director who has died aged 98, was one of the most influential film makers in Hollywood; although critics dismissed the majority of his films as (in the words of one) “brutal, exploitative and irresponsible”, many cinemagoers loved them.

Corman made directed and produced hundreds of films, and claimed that he could “count the financial flops on the fingers of one hand”. His productions, typically B movies, were lessons in ingenious speed and cost-cutting, making returns of perhaps $60,000 on budgets of $6,000 to $12,000.

His policy of employing unknown actors and technicians meant that he was responsible for launching or encouraging the careers of a number of stars (including Robert de Niro, Jack Nicholson, Dennis Hopper and Sylvester Stallone) and an equally large number of directors (among them Francis Ford Coppola, Nicolas Roeg, Jonathan Demme, Peter Bogdanovich, James Cameron and Martin Scorsese).

In his early career Corman’s concentration on directing cheaply made exploitation films like Teenage Cavemen, Bucket of Blood and She-Gods of Shark Reef earned him the sobriquet “The King of Schlock”. Corman sometimes rejected the label “B movies”, although he admitted that many of his films were made specifically for the teenage drive-in market.

Colleagues also recalled his talent for exploiting topical news events as the subject matter for quickly made films. When the Soviet satellite Sputnik was launched in October 1957, Corman began work 24 hours later on a film which he publicised as “a space melodrama set above the stars”, Battle of the Satellites.

His creativity as a director peaked in the 1960s, when he moved into his preferred genre and produced a string of cult horror classics including The House of Usher, The Pit and the Pendulum, The Masque of the Red Death and The Tomb of Ligeia. He then enjoyed further financial success tapping into what he described as “the drop-out beatnik market”.

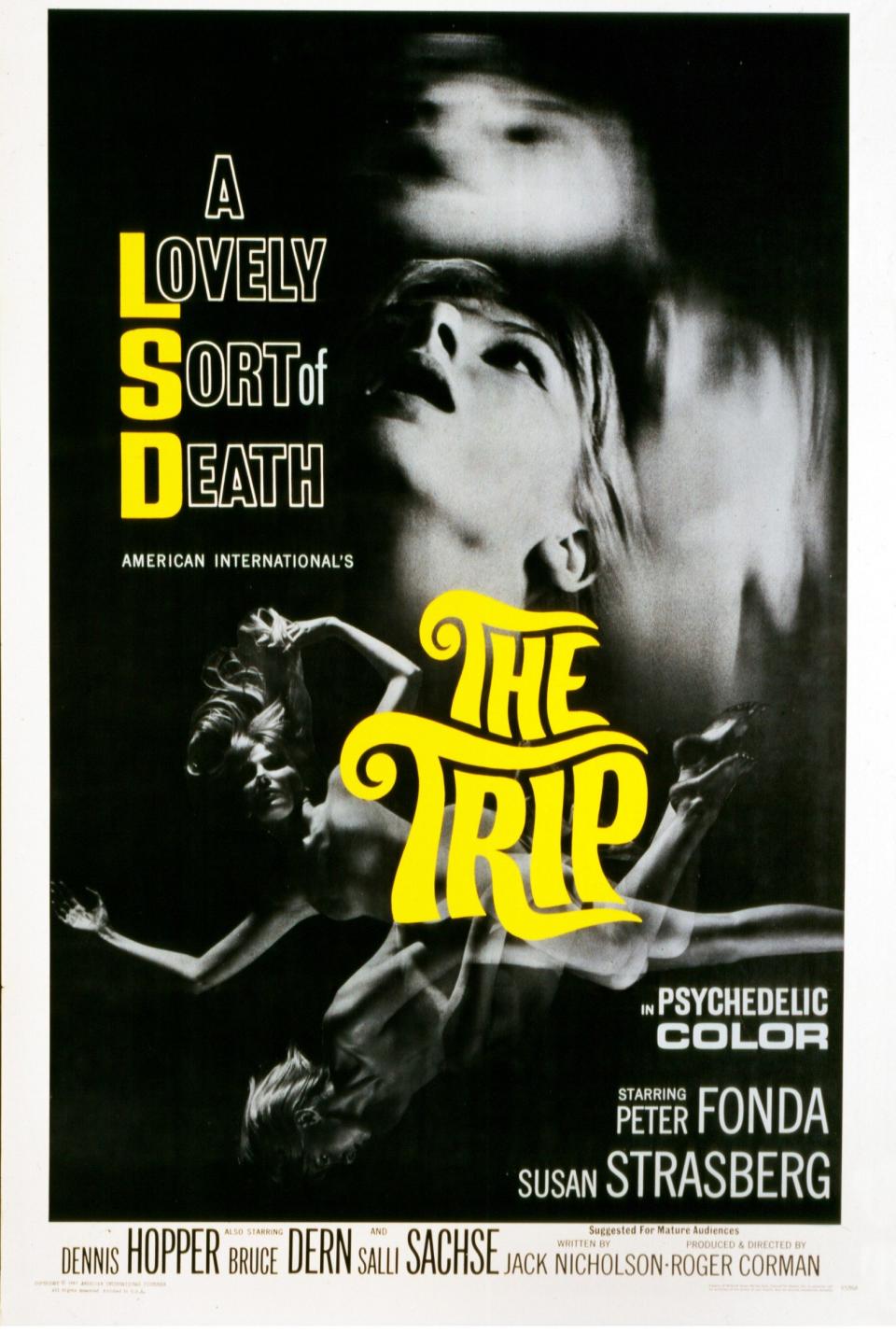

With films such as Wild Angels, a graphically violent account of motorcycle gangs in Los Angeles, and The Trip the following year (described by its critics as “an advertisement for LSD”), Corman won a new audience.

He maintained his reputation for cheaply made productions with The St Valentine’s Day Massacre (1967), where he used old sets from The Sound of Music and Hello Dolly to represent Chicago in the 1920s. In the space of 17 years he directed more than 40 films; over his whole career he produced or executive produced at least 300 (including, in 1963, Dementia 13, Francis Ford Coppola’s feature-film directing debut).

In 1970 Corman set up his own distribution and production company, New World Pictures. Projects such as Lady Frankenstein, Night Call Nurses and The Velvet Vampire made a considerable profit and Corman then surprised his detractors by investing the money in distributing what he described as “high-quality art films”.

He used the same marketing techniques which had publicised films such as Night of the Blood Beast to

promote movies by European directors including Ingmar Bergman (Cries and Whispers) as well as Akira Kurosawa, François Truffaut and Werner Herzog.

Corman also had a liking for taking small parts in films made by his various protégés, appearing in Coppola’s The Godfather Part II, as an FBI chief in Jonathan Demme’s The Silence of the Lambs and contributing a cameo to Joe Dante’s 1981 werewolf film The Howling.

Roger Corman was born on April 5 1926 in Detroit, Michigan, the elder of two sons of William Corman, a civil engineer, and his wife Anne. When he was 14 his family moved to Los Angeles, where he attended Beverly Hills High School, where he developed a fascination with film-making. In 1944 Roger joined the Navy, where he remained until the end of the Second World War.

On his father’s advice Corman then enrolled as an engineering student at Stanford University and after graduating began work as an engineer with US Electric Motors. Against his family’s wishes, he left the job four days later and became in his own words “a bum”. He worked for a period as a messenger-boy at 2Oth Century Fox and as a stage-hand for a local television company, before leaving the United States for Europe in 1950.

While in Britain he studied English Literature at Balliol College, Oxford, before moving to Paris in 1951. Later that year he returned to the US and found a job as a manuscript reader with a Hollywood literary agency.

“I saw all the ‘B’ movie crap that guys were sending in,” he recalled, “and I thought, ‘This is an easy way to make a buck,’ so I wrote a script called Highway Dragnet.” The agency sold the script to Allied Artists for $3,500 and Corman was employed as executive producer when the film was made.

Highway Dragnet was released in 1954 and Corman used the profits to finance another project later that year, The Monster from the Ocean Floor (featuring a giant squid-like creature). On the basis of these two excursions into film production, Corman persuaded American international Pictures to fund a series of films to be produced or directed by him.

Over the next five years he churned out 32 films for AIP, ranging from Westerns such as Apache Woman and Five Guns West (both 1955) to horror or monster films including Beast with a Million Eyes (1955), Swamp Woman (1956) and Attack of the Crab Monsters (1957).

Corman was equally at home with teenage exploitation films: titles included Confessions of a Sorority Girl (1957), Rock All Night (1957) and Teenage Doll (1957).

He enjoyed his first critical success with Machine Gun Kelly (1958), starring Charles Bronson in the leading role, and was then approached by 20th Century Fox to make I Mobster, another hard-edged gangster film.

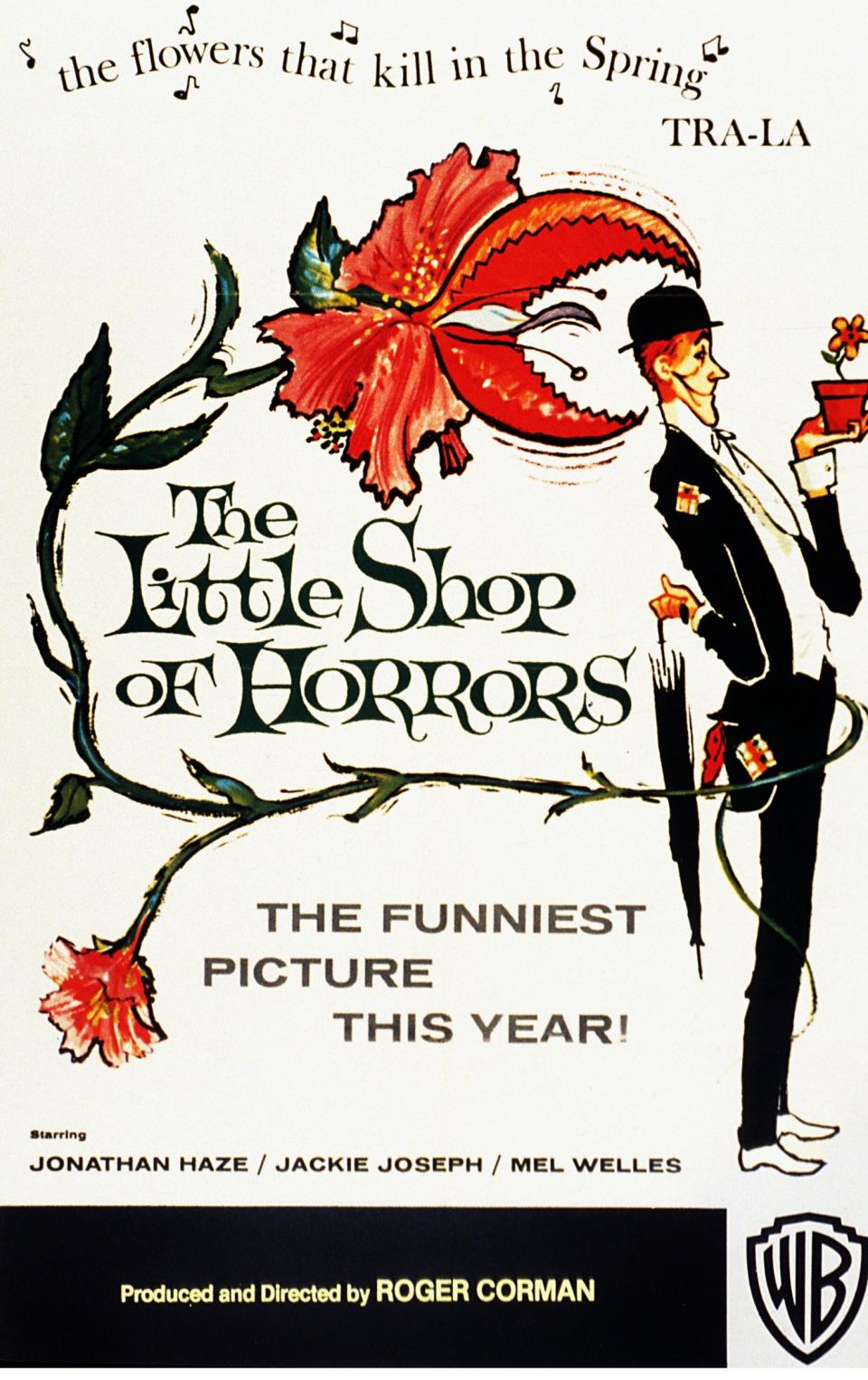

While enjoying a degree of acclaim that followed both films, Corman never stopped making the kind of films which had brought him financial success. In 1960 he made The Little Shop of Horrors, a spoof horror film which rapidly became a cult classic. “We made it primarily to have fun,” Corman recalled, “and also to break a record, because we did it in two days and one night.” The film almost certainly still holds the record for the shortest filming schedule in history.

By the early 1960s Corman felt that he had established a solid base from which to start making the kinds of films which interested him. He had been a devoted fan of Edgar Allan Poe since childhood and persuaded AIP to finance a more 1avish production, House of Usher (1960).

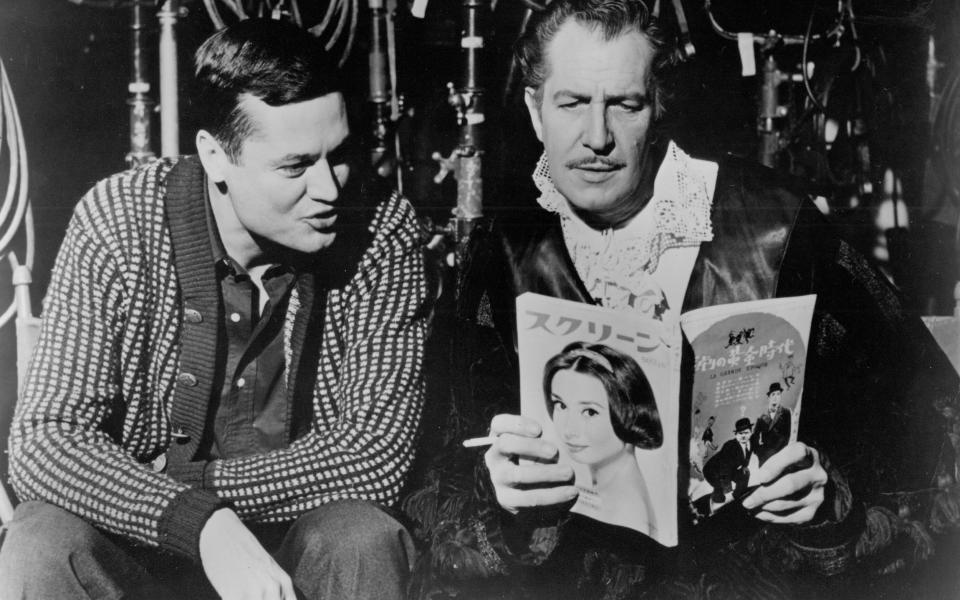

The film was enormously successful and gave rise to a series of adaptations of Poe’s horror writings, invariably starring Vincent Price, Peter Lorre or Boris Karloff.

In 1964 Corman shot two films in Britain which ranked among his best work. The first, The Masque of the Red Death, was distinguished by its impressive, surrealistic sets. “1 was amazed when I signed the deal with the studios,” Corman said. “They told us we could use anything in the scenery docks and it was all included in the price. As they had just finished filming A Man for All Seasons and Beckett there were these fantastically expensive sets lying around waiting for us to use.”

In his second British-based film, The Tomb of Ligeia (1964), Corman departed from his usual style and filmed the story in naturalistic settings, using ruined churches for outdoor locations. “1 went against my own rules,” he said. “I always said you should film horror in deliberately artificial environments as it heightens the sense of the macabre. With Ligeia I just couldn’t resist all these great old ruins and so we shot it outside, and I think it worked quite well.”

Returning to the US, in 1966 he started work on The Wild Angels, which starred Peter Fonda as the sadistic leader of a violent biker gang. Critics condemned the film as “vicious and irresponsible”, but Corman’s documentary style appealed to Europeans and the film was nominated as the American entry in the Venice, Film Festival. The film cost $360,000 to make and made more than $24 million at the box office.

Buoyed by its financial success, Corman directed another film starring Peter Fonda, The Trip (1967); with a screenplay by Jack Nicholson, it revolved around the protagonist’s experiences with LSD. The Trip gave Corman another big cult success.

His final film as director for AIP was Gas-s-s-s (Or It Became Necessary to Destroy the World in Order to Save It (1970). But AIP made cuts to the film of which Corman disapproved, especially the last shot, in which God comments on the action, and which Corman rated one of his best sequences.

The same year saw Bloody Mama, a bloody retelling of the life of the criminal matriarch “Ma” Barker, starring Shelley Winters, which did poorly at the box office and drew criticism for its graphic brutality, though David Thomson singled it out for praise as “a scathing portrait of maternal smothering”. Admitting that he felt as if his career was “no longer under control”, Corman went on to another flop with Von Richthofen and Brown later that year.

Angered at the way distributors re-cut his footage, Corman gave up directing to form New World Pictures, for whom he continued to produce the type of films he knew best, low-budget “shockers”. Of his retirement from directing he said he “had made too many pictures in too short a time. 1 just became tired.”

Among films he produced in this period, often given an opportunity to up-and-coming directors, were Night Call Nurses (1972, directed by Jonathan Kaplan, who went on to make The Accused); Boxcar Bertha (also 1972, Martin Scorsese); Caged Heat (1974, Jonathan Demme); Paul Bartel’s Death Race 2000 (1975); Grand Theft Auto (1977, directed by a young Ron Howard); and Joe Dante’s Piranha (1978).

In 1972 Corman married Julie Halloran, a former researcher for The New York Times who followed her husband into film production.

Hoping to rid himself of what he described as his “sleaze merchant” image, Gorman also began distributing foreign films by arthouse directors such as Bergman, Truffaut and Kurasowa, distinguishing himself from other distributors in the bold advertising techniques he employed.The formula was successful and Corman continued to promote foreign directors until by the end of the 1970s their films made up 20 per cent of New World’s releases.

In 1983 Corman sold New World Pictures for a profit of $16 million. He continued to distribute films, and returned to producing with yet more exploitation movies, few of which turned a profit.

He returned to directing in 1990 after a gap of nearly 20 years with a complicated adaptation of Brian Aldiss’s futuristic horror novel Frankenstein Unbound. Although not well received by critics, who complained that the plot was over-complicated and self-indulgent, the film managed to recover production costs.

The following year Corman acted as Dean of Studies for a British Film Institute seminar on low-budget film making. He used his company Concorde Pictures as an illustration of how to make films cheaply and quickly. “We produce one film every four weeks. That makes us the biggest producer of English-language films in the world.”

In the 1990s, he was executive producer on “Roger Corman Presents” for Showtime, a series of low-budget TV movies with titles like Bram Stoker’s Burial of the Rats, Terminal Virus, Vampirella and Shadow of a Scream. Many of his pictures went “straight-to-video”.

In the new century there was no sign of a slowing-down in Corman’s work rate. For the Syfy cable TV channel, for example, he produced Sharktopus (2010) and Piranhaconda (2012); and in 2013, a gamer film, Virtually Heroes, became his first to play at the Sundance Festival. Shot for $114,000 partly using repurposed stock footage from his library, it was, adjusted for inflation, the cheapest film he had ever made.

Corman’s autobiography was titled How I Made a Hundred Movies in Hollywood and Never Lost a Dime (1990). He received an honorary Academy Award in 2009 for “his unparalleled ability to nurture aspiring filmmakers”.

Outside film, Roger Corman was a follower of ballet. His survivors include his wife Julie and two daughters.

Roger Corman, born April 5 1926, died May 9 2024