Rock the Vote: How the Music Industry Built a Youth Voting Movement

On June 8, 1990, an undercover cop walked into a Fort Lauderdale record store, picked up a copy of 2 Live Crew’s As Nasty as They Wanna Be, and promptly arrested the man behind the counter. The Miami rap group was no longer free to be, well, as nasty as they wanted to be. In light of pop music’s increased tension with parent groups and conservatives, a federal judge had ruled the record legally obscene, and therefore illegal to sell.

Three days after the arrest, 2 Live Crew performed songs from the album at a nightclub in nearby Hollywood, Florida; afterwards, two of its members, Luther Campbell and Chris Won Wong, were stopped by local police and charged with “certain acts in connection with an obscene, lewd performance.” They would later be acquitted, but their arrest was a turning point in a long-simmering conflict between the government and the music industry—one that would eventually result in young music fans voting en masse.

In 1985, the Parents Music Resource Center (PMRC) successfully lobbied to place a parental guidance warning on albums containing sexual, violent, or otherwise explicit content inappropriate for young listeners. Senate hearings were held before record labels started voluntarily slapping warnings on their wares, and artists as disparate as John Denver, Dee Snider, and Frank Zappa brought their rightful ire to the stand. “It was quasi-government censorship, and it had a chilling effect on free speech of the artists,” says Jeff Ayeroff, who was then an executive at Virgin Records.

A vocal critic of the PMRC, Ayeroff had cut his teeth in the creative departments of A&M and Warner Bros. Records. He’d worked with some of the talent the committee found to be particularly “objectionable,” including two key players on their “Filthy Fifteen” list: Prince, whose “Darling Nikki” topped the list, and Madonna, the committee’s dirty muse of sorts. (Susan Baker, the wife of treasury secretary James Baker, established the committee with future Second Lady Tipper Gore after her young daughter had asked her to explain the lyrics to “Like a Virgin.”) Now, just a few years later, Ayeroff was witnessing the actual outlawing of albums—no doubt the influence of the PMRC-led culture wars. He knew he needed to act.

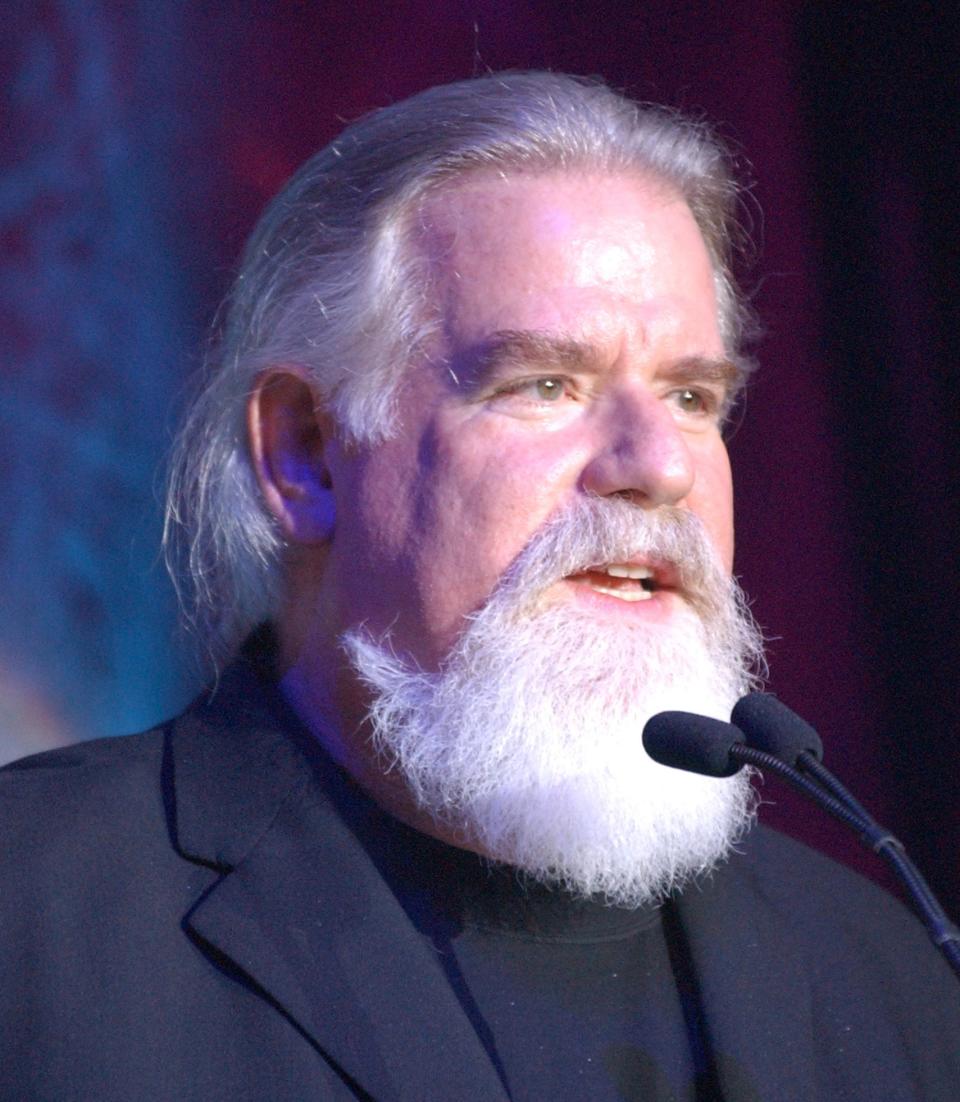

MTV Rock The Vote 10th Annual Patrick Lippert Awards

Jeff Ayeroff, photo by Jeff Kravitz/FilmMagicAyeroff saw a connection between the deepening cultural canyon, and age difference, between the record-buying public and this committee of “mothers protecting people from music,” who had close ties to lawmakers. He was sick of conservatives weaponizing popular music, specifically rap and rock, as a way to scare older voters while ignoring the interests of young ones. The PMRC was well-connected in Washington, but Ayeroff was well-connected in the entertainment industry. He could bring his experience and network to an initiative that ostensibly countered these stifling politics and encouraged young voters to get involved. With the help of his assistant, Beverly Lund, and his partner at Virgin, Jordan Harris, Ayeroff founded Rock the Vote, a bipartisan nonprofit organization focused on voters between the ages of 18 and 29, before 1990 was even over.

“The reality is, the big stars, we don’t make [them]—we just turn them onto things and put the money behind them,” he says. “The same idea applies to politics, to getting kids to vote. If I can market Madonna, Prince, and the Talking Heads, I can market voting.”

Over the course of his tenure at A&M and Warner, Ayeroff had helped put together some of the more memorable music videos of the 1980s, from the Police’s “Every Breath You Take” to A-Ha’s “Take On Me.” He was a self-described “prime supplier” for MTV since its earliest days. Now the network was facing pressure from the PMRC to adjust its programming, due to concerns including the “exceptional savagery” of heavy metal videos. Ayeroff pitched his new project to MTV founder and former president/CEO Tom Freston, who was already interested in diversifying the network’s offerings with socially minded programming.

“We had determined that rather than just play music videos, which were beginning to wear a bit, we could also be about [what] the music was about: news, fashion, politics,” Freston says. “Those were things our audience was also interested in.” MTV had amassed millions of viewers since it launched in 1981, and Freston wanted to use its sizable influence for good.

“For the first time ever in the world, there was one radio station, and it just so happened to be on television,” says Ayeroff of MTV’s reach at the time. “Kids all over the country would see the same program, see the same videos, hear the same interviews. They would watch the same commercials.” Crucially, they would also see the same public service announcements.

Before the 1990 midterm elections, Ayeroff knew the darling of his former label, Madonna, had time coming up in the recording studio with one of his artists at Virgin, Lenny Kravitz. He scheduled brief shoots with their respective teams. The goal was to create a public service announcement with the look and feel of a music video, one that could run as counter-programming to the actual videos on MTV—and one that was easy for the artists, their labels, and Rock the Vote to pull off.

“You say to the manager, ‘Ask your artist if they want to do a Rock the Vote spot. We’ll do it inside the budget of your own video shoot: You spend another two hours or 20 minutes on the set, depending on how simple an idea it is, and we’ll get you more visibility vis-a-vis airplay,’” explains Ayeroff of the early process. “It was like getting a free ad on MTV.”

There was just one minor snag: Neither Madonna nor Lenny had registered to vote before filming their PSAs. (From then on, voter registration forms were brought to Rock the Vote shoots.) Still, the Madonna shoot in particular was inspired. Directed by Paula Greif, who’d helmed videos for Duran Duran and the Smiths, the PSA actually came to life in the director’s West Village apartment. Greif’s place was bathed in natural light, so she invited Madonna and her dancers over.

“It was shot in a simple way on this white background, to be very graphic and very direct,” Greif says. “She brought an American flag to wrap herself in, but she didn’t have anything to wear [underneath]. I had some red underwear that I gave to her. Someone stole the red underwear—it disappeared that day!”

Greif’s frequent collaborator, culture writer Glenn O’Brien, tweaked the lyrics of Madonna’s “Vogue” to give it a political update. Soon, the most popular pop star on the planet was draped in an American flag and riffing on her then-biggest hit with a Rock the Vote twist: “Dr. King, Malcolm X / Freedom of speech is as good as sex… Don’t just sit there, let’s get to it / Speak your mind, there’s nothing to it.” It was nothing short of iconic. “We were talking to music lovers and just trying to get them to vote,” Greif adds. “We tried to make voting cool, basically, and I think we did.”

Freston puts it more bluntly: “The minute we saw it, we played it all day long.”

From then on, artists across the pop spectrum—from Michael Jackson to Deee-Lite to LL Cool J—took Ayeroff’s prompt and ran with it. Megadeth’s 1990 PSA was a striking contrast to Madonna’s, as the guys all posed with an American flag, completely silent, with gaffing tape covering their mouths as YOUR VOTE IS YOUR VOICE flashed beneath them on the screen. R.E.M. filmed multiple PSAs, and in conjunction each copy of their smash 1991 album, Out of Time, was sold with a postcard petition for the Motor Voter Bill, which ensured that people could register to vote at the DMV.

In the lead-up to the 1992 presidential election, Aerosmith goofed off with their own “Bill of Rights” PSA, one that celebrated “the right to make love in an elevator.” Madonna recorded another PSA in 1992, where she chatted about the voting process with the raunch and camp of a ’90s Mae West. “[Voting is] kind of like sex with my boyfriend,” she drawled. “I mean, what do I get out of it? I’ll tell you what I get out of it: A good night’s sleep, because if I have to listen to him complain one more night about how I’m not a responsible citizen of this country...”

The first presidential election in Rock the Vote’s history was a win, both for the organization and its preferred administration (Tipper Gore notwithstanding). The Choose or Lose: Facing the Future with Bill Clinton town hall, a joint venture between Rock the Vote and MTV, made for instant legend. The Facing the Future audience was full of prospective voters in Rock the Vote’s coveted demographic: teens and young adults sporting scrunchies, T-shirts, goatees, and Contempo Casuals sundresses volleyed questions at Clinton about everything from Anita Hill (he said he believed her) to his first “rock’n’roll experience” (loving Elvis). Affable and at ease, Clinton made it clear that no topic was off-limits, not even drugs (“I didn’t inhale”) and his preferred style of underwear (boxers).

When he won the election, young voters played a crucial part in his victory. There was a 37 percent increase in participation in voters between the ages of 18 and 24 compared to the previous presidential election, the largest turnout for that group since 18-year-olds were given the right to vote in 1972. MTV and Rock the Vote threw their own inaugural ball to celebrate, where Clinton made a point of thanking them.

“I think his exact words were ‘MTV and Rock the Vote were a major reason’ that he won the election,” Freston says. “That would just send a chill down your spine. [MTV] started out in the gutter in 1981, and 11 years later, you’ve got the President of the United States crediting you in part for helping get him elected.”

President Bill Clinton at MTV's Rock The Vote

After the rousing success of their inaugural presidential campaign, Rock the Vote revved up once again four years later. In 1996, one of the artists leading its charge was Sheryl Crow, who’d broken through a few years earlier with a folksy rock sound and was on the brink of releasing her self-titled second album. Like Ayeroff, Crow had been incensed by the threat of censorship brought on by the PMRC; she would later frequent Capitol Hill to advocate for musicians’ rights in regards to copyright and other matters. One of her earliest appearances with the organization involved clicking through the very first online voter registration form and demonstrating how to use this newfangled technology for a small group that included Vermont Senator Patrick Leahy.

“It’s funny because the internet was a new thing, and I was like, ‘What is it called?! The world wide web?’” Crow recalls, laughing. “I remember introducing that, and it was like a new video game: ‘And then you tap this, and then you go here, and then that’s going to take you to here.’”

For Crow, Rock the Vote’s youth outreach wasn’t unlike the engaged dinner-table conversations she’d have with her parents—one liberal, one conservative—back in Missouri, and that aspect of the organization’s mission compelled her to answer Ayeroff’s call. “The younger generation that may be feeling hopeful, disenfranchised, or apathetic—that’s not a new thing for that age group,” she says. “Rock the Vote really tapped into that, and still does. They say, ‘You live in a country that’s amazing in the fact that you are [supposed] to be guaranteed the right to a safe voting experience, and it’s your duty to show up and be a part of that.’”

Chuck D also began working with Rock the Vote in 1996. Like Crow, he had grown up in the ‘60s and ’70s, and galvanizing events like the protests against the Vietnam War left an imprint on his political consciousness. Fans of the Public Enemy leader knew him for his lyrical bombast and dexterity with socio-political commentary, and he brought that same insurrectionary spirit to his PSA. Referencing his group’s indelible “Fight the Power,” Chuck stands on a bustling Brooklyn sidewalk and asks: “What is power? Can you feel it, see it, hear it? Nah, but you know it’s real when it’s against you.”

“I was clear from the jump that I come from a different time, where people got beat down for the vote,” he says. “I wanted to be able to get involved with a situation that used culture at the particular time to at least [encourage] people to think for themselves. I thought I could energize people younger than me to understand that voting was as essential as washing your ass in the morning. You don’t have to vote, but you can’t go around telling people that something stinks.”

Starting with the 1996 election, Rock the Vote knew they had to go further than the limits of MTV. They started sending artists into the field—meeting with voters in swing states and performing at Rock the Vote concerts—and helped revive the role of popular musicians in politics in the process. In 2000, Chuck D worked with the organization on Rap the Vote, a joint effort with Russell Simmons to mobilize young Black voters. Four years later, a Rock the Vote bus tour rolled through 50 cities across the country with a rotating lineup that included the Snoop Dogg/Nate Dogg/Warren G supergroup 213, Q-Tip, the Black Eyed Peas, the Donnas, and the (Dixie) Chicks, who had just infuriated country radio with their passionate criticism of George W. Bush’s invasion of Iraq.

Despite this heightened engagement, the first half of the 2000s represented a dark time for Rock the Vote—in addition to Bush’s election and re-election, the organization faced financial woes in 2006, though it eventually recovered. But Barack Obama’s presidential bid revived interest in the young electorate, and artists ramped up their support, too. Crow even gave away free downloads of her 2008 album, Detours, to those who registered through Rock the Vote, motivated in part by her feeling that the American people had been lied to by President Bush regarding Iraq. After visiting Obama’s campaign headquarters shortly before the election, she ended up performing at his inaugural festivities in 2009.

“Standing in a vast field of people watching a Black man being inaugurated was one of the greatest moments,” Crow says. “To me, there was a direct correlation to having gone out and campaigned for him—but not only that, having gotten people to register to vote, no matter what side they stood on, no matter what their political beliefs were.”

By the 2008 election, Rock the Vote had registered their two-millionth voter. Obama’s historic victory was particularly meaningful for Ayeroff, who felt Obama embodied everything he had hoped Rock the Vote could achieve.

“People say that politics is just show business with ugly people, until you get to Clinton, who was handsome, and Obama—and then all of a sudden politics is like show business,” he says. “I looked at Obama and I said, ‘This guy’s a fuckin’ rock star.’ He was, to me, the fruition of the idea of youth voting—the idea that the electorate changes, and ultimately, that the politicians would change.”

Rock the Vote continued to build relationships with artists who weren’t afraid to step into the political arena, or who had long since found their place within it. The next generation of pop stars would channel Madonna’s PSA in subsequent decades: Christina Aguilera, holding her newborn son, wrapped herself in the flag and sang “America the Beautiful” for her 2008 PSA.

The scope of Rock the Vote’s operation has grown since then, evolving to meet the moment: Instead of on-air PSAs, recent campaigns—like their Voter Registration Day push bearing a Shepard Fairey portrait of Snoop Dogg—have been tailored more to the Instagram set. Midterm elections, historically, receive a dismal response from young voters, and Rock the Vote targeted that disinterest in 2014 with a Lil Jon-led “Turn Out For What” video that threw back to the high-profile PSAs of years’ past. They registered close to 700,000 voters that year, a vast improvement from the 250,000 they’d signed up for the prior midterms, with 20 percent of that age group casting a ballot. That number was eclipsed in 2018, when it rose to 31 percent and broke records for the highest youth turnout since the ’80s. Crow may have tried out the very first virtual registration form, but celebrities are now powering their own youth outreach efforts with Rock the Vote’s registration technology, as LeBron James did this year with his organization, More Than a Vote.

As for Snoop Dogg, he may have participated in Rock the Vote events in the past, but the 2020 election will mark his first time voting. According to Carolyn DeWitt, Rock the Vote’s president and executive director, Snoop was led to believe that he didn’t have the right to vote due to his criminal record. “The message that he’s sending isn’t just ‘I’m voting for the first time and you should, too,’” she says, “but also that we have to investigate what our rights are when it comes to having a voice in the future of our community.”

Rock the Vote has continued to reach voters across genres and generations by sticking to Ayeroff’s initial plan: put the music industry to work for the greater good. In spite of the staggeringly high stakes of this year’s election, he’s encouraged by the efforts he’s seen from young people, from the activism of Marjory Stone Douglas High School students to Billie Eilish, who will vote in her first presidential election this year and is vocally encouraging her fans to do the same. The celebrities, PSAs, and successful social media campaigns have all done their part, but the message has always been more important than the medium.

“There is one thing that ties this all together,” Ayeroff says. “The youth vote has the potential to save the world.”

Disclosure: The writer was previously employed by MTV News.

Originally Appeared on Pitchfork