Robert Plant interview: ‘I’ve got a very hefty book of guilt and maudlin apologies’

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

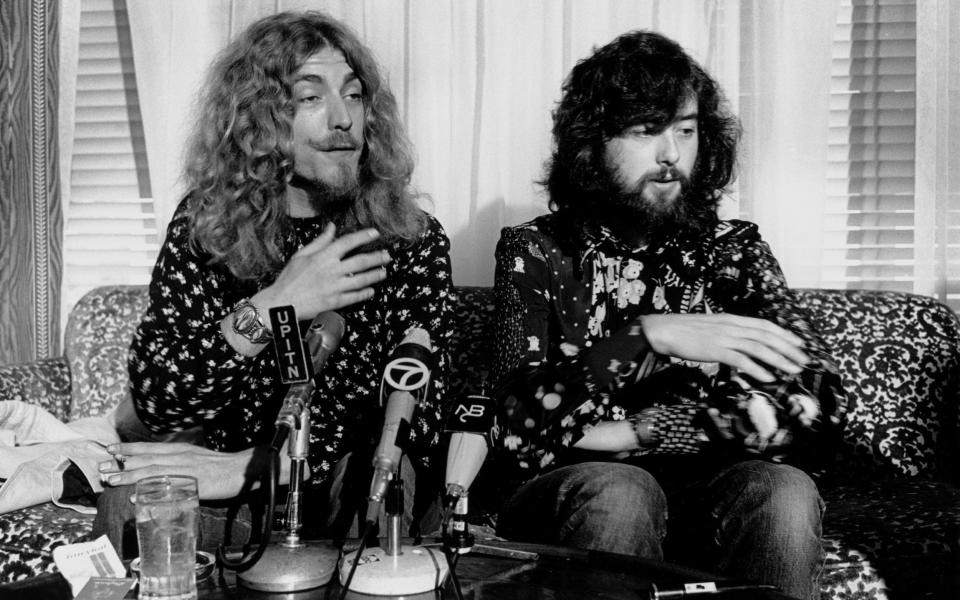

Heads turn as Robert Plant strides into a quiet pub in Primrose Hill, dressed in black, a cascade of faded blond curls framing a jowly, lined face and scrub of grey beard. At 73, the “golden god” of 1970s heavy rock has taken on the bearing of a magnificent old lion. “I was 19 on the first Led Zeppelin rehearsals, and I was 32 when [drummer] John [Bonham] passed away, that awful time,” he notes, as we sit over coffees in a quiet corner. “People used to say to me, ‘Well, you must have done enough now?’ Enough of f------ what? ‘Enough to retire!’ So imagine the blessing to be 40 years further down the road, and I still don’t know enough to stop in any respect. There’s always something new to learn, somewhere new to take it. I love it.”

Plant has made 16 albums in the four decades since Zeppelin split in 1980, in all kinds of adventurous and experimental musical configurations, incorporating everything from North African desert blues to spaced out rockabilly. He never stops scribbling lyrics. “I’ve got a very hefty book of maudlin apologies and guilt. It’s a lifetime’s job,” he says.

This is how Plant talks, in poetically elaborate phrases, jokes and riddles, peppered by chuckles and mysterious allusions left open to interpretation. It is a playful way of engaging with interrogation, with built in wiggle room, reflecting an amiable unwillingness to be pinned down. This gnomic style is partly a shield aimed at protecting himself from the considerable weight hefted by his world-beating former band. “It was just dumbf---, a lot of it,” he says, looking back on Zeppelin’s 12-year reign of extraordinary music and notorious hedonism. “It would be trite to say the actions fit the circumstances there on the spot at that time. We made great music. We had a great time. And then it stopped. That’s all I know about it.”

Age is not something Plant worries about, for reasons that carry considerable heft. “I think I got really old when I was 29, when we as a family lost the key man,” he says, reflecting on the death of his five-year-old son Karac in 1977, from a stomach virus. “So many parts of our being, exuberance, optimism and physicality and the whole wear and tear of life has fluctuating time periods where it plays different cards for you,” he offers, sagely. Plant has three surviving children, from two relationships, but has never remarried since his divorce from Maureen Wilson in 1983. “What I try and do to keep the Grim Reaper at bay is to be around people who are funny and kind. That’s the panacea for me, that helps me through.”

Plant has a new album with American bluegrass singer Alison Krauss, Raise the Roof, a long overdue sequel to their multimillion-selling, five-time Grammy award-winning 2007 album Raising Sand.

Once again, the two singers from different ends of the musical spectrum combine their utterly distinct voices to spine-tingling effect, reimagining lost country, soul, folk and blues songs as spookily atmospheric sketches and dreamy jams with an all-star band of masterful session players marshalled by producer T Bone Burnett. “It’s all part of paying homage to the great treasury,” says Plant. “It’s almost like taking a cloth to an old painting and clearing the glass and seeing what was there before and then trying to do a study on it.”

Plant’s enthusiasm for music is deep and infectious, and he peppers the conversation with references to records he loves and artists he admires, diving into the musicological history of styles that have influenced him. As a teenager growing up in the Black Country town of West Bromwich, he found it was Chicago’s Chess records label and the raw blues of Howlin’ Wolf, Muddy Waters and Willie Dixon that lit a fire under him. “As British kids, it was such a relief for us to find that outlet of expression.” From the age of 16, he was fronting local blues bands. “You want music that’ll blow the ducks out of the pond when you’re trying to get above the sound of adolescence. But I did hang around folk clubs, too, and there was poetry and jazz recitals, and unaccompanied singers delivering She Moves Through the Fair with a finger in one ear. You know, no flattened thirds, no schmooze, just sing the song and it’s beautiful.”

Plant and Krauss do a deeply tender version of Anne Briggs’s Go Your Way on their new album. Briggs was a key figure in a sixties English folk revival that influenced the more pastoral side of Led Zeppelin. Plant rhapsodises about her and Dave Swarbrick, Sandy Denny, Davey Graham, Bert Jansch and folk fusion bands Fotheringay, Fairport Convention and Pentangle. “Its great to have a clarion for those guys who gave new life to some magnificent music from our shores,” he enthuses. “If you listen to June Tabor and Maddy Prior singing together, you hear the pathos of those harmonies, that crossed the ocean hundreds of years ago and settled in the hills of Appalachia, where its alive and well and people are still singing together as a family.”

Krauss grew up in Champaign, Illinois playing fiddle and singing just such songs. On a Zoom call from Nashville, she gets suddenly tearful recalling the lifechanging impact of seeing sibling bluegrass artists Jim & Jessie, the Osborn Brothers and the Del McCoury Band at a County Fair in 1979. “It’s singing so close you can’t tell one voice from another. It makes me emotional just talking about it, it’s so sweet,” she says. “It is precision singing. As a lead rock vocalist, Robert is so much the opposite of that. The ranges of our voices land in different places, and the fact that it doesn’t blend is what makes the blend. It creates a third voice.”

"It’s like being at night school,” says Plant. “I’m still learning the different flexing of harmonic options. You can hear me fitting in almost like some sort of vocal jigsaw puzzle.”

When I ask if this is difficult for him, he says “Oh yeah, it’s hellish! It’s a whole different mindset,” says Krauss. “It creates quite a feeling to hear him in that harmony role, because the identity of his lead singing is so powerful. It’s a voice that’s been part of everyone’s musical experience for decades.” When Plant and Krauss toured together during 2008, they performed Led Zeppelin’s Battle of Evermore, with Krauss singing Sandy Denny’s parts (the sublimely talented Fairport Convention singer who died in tragic circumstances at the age of 31 in 1978). “I’d look over, and there’s Robert, and I just got chills.”

There are no big Zeppelin wails on the new album. “When you think about the big voice, I was young, and perhaps I had to be as big as myself,” says Plant. “But I was always playing with my voice, and learning, and one of the things I wanted to learn was restraint. I love being a singer. We don’t have any pedal boards, no effects racks, we’ve got nothing at all except the option to mix it up and move things around. Whether it’s The Rain Song in Led Zeppelin or singing (the Everly Brothers’) Price of Love with Alison, you work to the song. I used to play The Starving Rascal in Brierley Hill outside of Dudley for eight quid singing (Chuck Berry’s) Bye Bye Johnny. To get from there to here, it’s magnificent.”

Plant notes, with tones of wonder and admiration, that several of his grandchildren play in bands now. “We’ve had our time,” he says, as if pondering the end of the rock era. “But two generations from when I first started being addicted to this, I’ve still got a foot on the pedal, I’m still going somewhere. It’s the prerogative of a madman! Oh yeah!”

Robert Plant and Alison Krauss: Raise the Roof (Rhino) is out today