Robbie Robertson talks new album, new Band doc, 'The Irishman,' and 'unimaginable' early electric gigs with Dylan

More than 50 years into his career, Robbie Robertson is busier than ever, juggling several exciting projects that are all tied together in some way via his 40-year partnership with filmmaker Martin Scorsese. Robertson just released his excellent, noirish sixth solo album, Sinematic, and some of its tracks, including the Van Morrison collaboration “I Hear You Paint Houses,” are connected to his score for Scorsese’s new mob epic, The Irishman. Additionally, the Scorsese-executive-produced documentary Once Were Brothers, about Robertson’s revered and influential group the Band, just premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival to great acclaim. And coinciding with the doc’s release, it has just been announced that the Band’s seminal sophomore album is getting the deluxe reissue treatment later this year.

“It is one of those ‘when it rains, it pours’ times, I guess, in such a good way, right now,” Robertson tells Yahoo Entertainment. “And it wasn't planned, but because I was working on all these different projects at the same time. Usually you try to keep this one over here and that one over there, and in this case I just opened my arms and I invited them all in, and a lot of it comes out in the songs on Sinematic.”

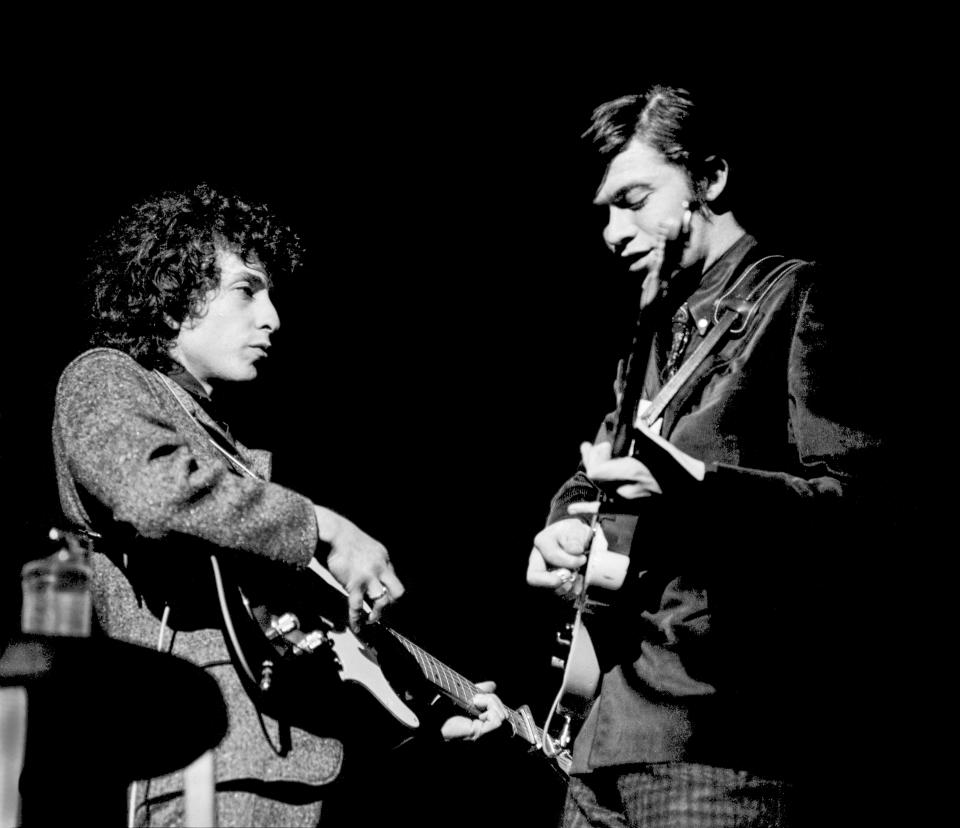

Robertson has weathered many changes in his career with and without the Band. And early scenes in Once Were Brothers of Robertson’s then-little-known Hawks (who later evolved into the Band) backing Bob Dylan on his 1965 tour — during Dylan’s “Judas” period, when he first controversially went electric — amusingly demonstrate just how tough, resilient, and focused he always was. The archival footage shows hostile Dylan concertgoers practically rioting, and even chasing the police-escorted Dylan and the Hawks out of one venue. (“Stop booing me,” Dylan drily tells the “fans” swarming his car.) Robertson recalls the chaos with a wry laugh and a downright punk-rock attitude.

“I had never heard of anything like this before, or even since,” Robertson says. “That's a long time ago — this was in the end of 1965 and the beginning of 1966 that we did this. We played all over North America, all over Australia, all over Europe, and we got booed every night. Every night. This is unheard-of. It's unimaginable.

“When you're doing this, you would think, after six concerts of doing that, you would say to one another, ‘This isn't working out, maybe we should do something different.’ No. It worked the opposite way on us. We really went to a place of: ‘Oh, yeah? In your face!’ Bob was just like, ‘Turn up. Just turn it up more,’” Robertson chuckles. “So, it became a challenge unlike anything imaginable, and we got through it alive. Sometimes it was a little iffy. There were people that stormed the stage in madness and craziness you know? With scissors! …But we survived it. We got through it. We came out of that with thicker skin, I'd say.”

Nearly a decade later, in 1974 — after achieving their own massive success with five studio albums — the Band went back out on the road with Dylan, this time playing to adoring crowds. Robertson admits that the completely different audience response was vindicating. “We didn't change a thing. The world changed,” he marvels. “The world came around, and there was a bold feeling about that — just to think you were doing something and everybody was wrong and we were right!”

Always open to change himself, Robertson is already looking ahead to his next film with Scorsese, Killers of the Flower Moon, a Native American epic that he promises will be “unlike anything that you've ever seen or heard before.” It’s a project that will no doubt have special resonance for Robertson — who spent much of his childhood on Toronto’s Six Nations Reserve, where his mother had grown up — though he says he’s “still trying to figure out” his approach to that score.

However, as for his score for The Irishman, which so affected the sound of Sinematic, Robertson says, “On this one, I had to discover a musicality. This movie takes place over many decades, and I had to find a sound, a mood, a flavor, that had a timeless quality to it — that it didn't sound like it was stuck in any one of these decades.” Explaining his decades-spanning overall relationship with Scorsese and what exactly it is about their dynamic that’s so magical, Robertson can only muse, “It's a bit mysterious, in that there is something in my imagination, and in understanding something deeply about him and his working process, that he kind of thinks, ‘Oh, he gets it. He understands something about what I'm trying to do.’ And likewise.”

Robertson describes the Irishman-adjacent sound of Sinematic as “Peckinpah rock,” explaining, “There is in there an extreme beautiful darkness, and I like that. I like the noir element to it. And working with Martin Scorsese on this thing, and all the stuff that was swimming around while I was making this, it just had that element. There's somewhat of a balance in it, too. It isn't all violent… [but] I was working with Martin Scorsese and we're doing a mob movie. [The album] is not about little sweetheart people!”

Robertson does sound like a sweetheart of sorts, however, as he emotionally gushes about his history with the Band and the fantastic reception for Once Were Brothers at the Toronto International Film Festival. “We had one of the most unusual and extraordinary stories of any group in music history. There is nothing comparable to it. … What this documentary is about, really, is a lot about the brotherhood. We were so locked in, in a musicality and in a personal way, that we invented something that had a big effect on the course of music. … It sent ripples through music, and through the culture. … We weren't trendy, because we didn't know what the trend was, and didn't want to. We were going into our own world, our own dimension, and discovering a musicality, a sound, everything.” A song on Sinematic, also titled “Once Were Brothers,” bittersweetly chronicles the unraveling of the Band.

The 50th-anniversary deluxe edition of The Band, out Nov. 15, will feature one the group’s biggest culture-shifting moments: their 1969 performance at Woodstock, which has never been officially released on record. Robertson, already accustomed trying to win over crowds due to his Dylan/Hawks experience, recalls the scene – this time garnering a much more positive response than he did in 1965. Suffice to say, there was no rioting with scissors that day.

“We had only played, I think, one job before as the Band before playing in front of a half a million people. When we walked out on that [Woodstock] stage, there were people as far as the eye could see, everywhere in every direction. It was a stunning sight, a powerful sight, but [the hippies] were there to party and to rock. … And we went out and when we played, it was equivalent to doing a set of hymns. Everybody was stopping. They weren't jumping anymore, and this spell came over the place. I don't know if it was the right place and time, but everybody went there with us and this thing came over everybody, and there was something beautiful in that.”

Watch Robbie Robertson’s full, extended Yahoo Entertainment interview above, in which he talks about his work with Martin Scorsese, Once Were Brothers, and his bittersweet Band experience, and takes us on a visual track-by-track tour of his artwork for Sinematic.

Read more from Yahoo Entertainment:

Robbie Robertson chronicles the end of the Band in bittersweet new song 'Once Were Brothers'

Robert De Niro talks de-aging VFX while debuting new trailer for 'The Irishman'

Follow Lyndsey on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Amazon, Spotify.

Want daily pop culture news delivered to your inbox? Sign up here for Yahoo Entertainment & Lifestyle’s newsletter.