‘Roadrunner’ Director Morgan Neville on the Mystery of Bourdain’s Suicide and Exploring Hours of His Show

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

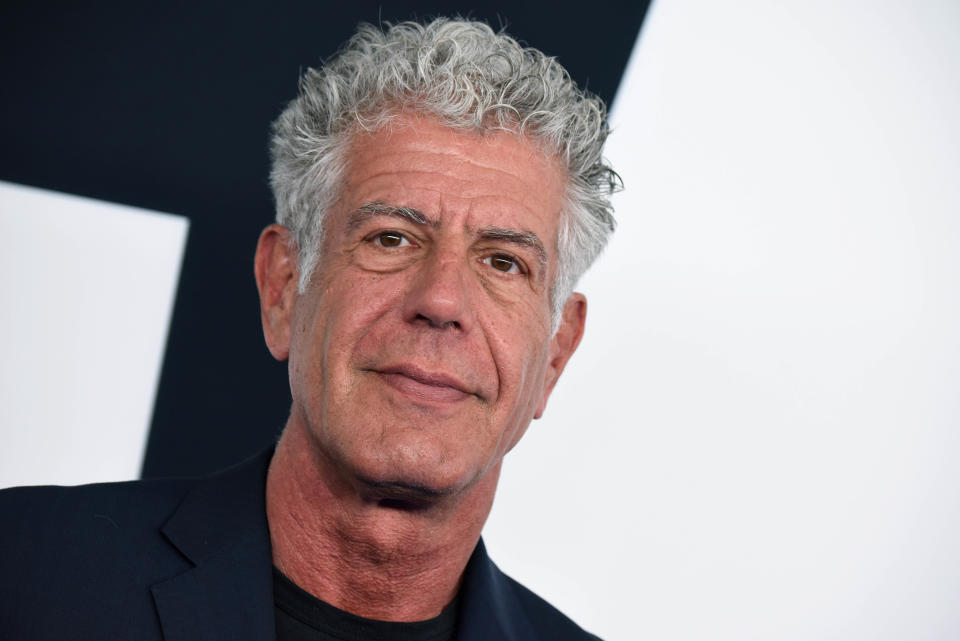

By the time Anthony Bourdain committed suicide in 2018, he had lived many lives. The “Parts Unknown” host became an unwitting celebrity chef with the 2000 publication of “Kitchen Confidential,” his behind-the-scenes exposé from his days in the high-end restaurant business. His bold truth-telling and acerbic tone easily translated to TV success, which Bourdain carried across three programs as he increased in ambition. At the height of his fame, Bourdain had his own genre of storytelling, using food and travel as a platform for studying people and places around the world.

The success came at great personal cost. In “Roadrunner,” documentarian Morgan Neville explores the hardships of Bourdain’s globe-trotting lifestyle, from the way it impacted his family life to the combustible relationship he developed with his many peers. Combining ample behind-the-scenes footage from the shows with over a dozen talking heads, “Roadrunner” provides an enthralling deep-dive on the evolution of Bourdain’s talent as well as the history of addiction that haunted him until the end. The movie also delves into the choppy final months of Bourdain’s life, when his public relationship with actress Asia Argento became intermingled with her #MeToo struggles and the host alienated himself from many of his regular collaborators.

More from IndieWire

“Roadrunner” simultaneously resurrects Bourdain’s endearing persona and provides a tough assessment of his biggest flaws. Neville, whose recent documentary work includes “Won’t You Be My Neighbor?,” is no stranger to peeking behind the veil of celebrity to find the true personality beneath the surface.

He spoke to IndieWire about the process of unearthing Bourdain’s story from the footage at his disposal, as well as how the mystery of his suicide became more central to the movie than anyone anticipated.

How much footage do you estimate you went through?

There was anything from 60 – 100 hours of footage per episode. There were 96 episodes of “Parts Unknown.” That’s just “Parts Unknown.” Then there was “No Reservations” and “Cook’s Tour.” Not all the raw footage exists for those episodes, but it does for certain seasons. Of course, we didn’t go through all the footage, that would’ve taken years and years. We probably went through 10,000 hours. We had six of us all looking at footage, sometimes double-timed, because there was so much to go through. I love archive docs, and this was a unique one because the camera was always there and running. It becomes its own weird, interesting verite thing. It has a behind-the-scenes quality that feels raw, which I wanted to carry over into the telling of it.

How did you narrow down the process?

We were going through footage for at least a year. Anytime there was an episode that he talked about or a crew member mentioned, we’d go through those episodes. There were definitely a number of episodes that were easy wins. A lot of the domestic ones. Or whenever Tony was on a beach. You can see that he’s in a different gear in those episodes. It’s pretty easy to tell early in a scene where Tony is phoning it in or actually wants to learn about a person. Those scenes floated to the top pretty quickly.

Given how much of his shows were infused with his personality, what surprised you about the way he came across in this additional footage?

One of the biggest challenges early on was not to make the film feel like the show. Among the things that really surprised me was that he was fundamentally a shy person. Once you hear that, it makes sense — you can see that in him — but I don’t think it’s otherwise obvious. He overcame it in a big way, but there was always a part of him that was a little walled off.

When I was first talking to people who worked on the show, they would say, “Tony had this technique, and we didn’t know it was his technique.” When he was shooting a scene with someone he didn’t know, he would open up about himself in a really raw way. The crew would be sitting there wondering when he’d get to the point of speaking about the subject. Eventually he would, but by speaking about himself, he would get other people comfortable talking about themselves.

Of course, they cut all that stuff out of the show. But the raw footage has a lot of Tony revealing a lot about himself to people — knowing it was never intended for broadcast. It was part of who he was. I remember talking to David Simon about Tony and he said the first time he met Tony, the first thing he said was, “Oh, you’re from Baltimore. I tried to score heroin once there and couldn’t.” To which Simon replied, “Then you must have been a terrible junkie.”

There are a lot of theories about what kept Bourdain going for so long. What’s yours?

There’s a scene with him and Chris Doyle in Hong Kong felt revealing because Chris is throwing him off. He starts saying, “Let’s talk about your crew.” And it just starts to get really interesting. That was one of those where I felt like I learned something about Tony in that raw footage.

What about the first scene, where he talks about what he wants to happen when he dies?

The footage of him at the start was in Provincetown, Massachusetts, where he’d worked for a number of summers. The tourist trap there was the first time he’d ever worked in a kitchen. He’s standing there in front of the house he rented and remembering that time in his life when he was just becoming an adult and finding his way in the kitchen, figuring out the beginning of his path. We see him being reflective about himself in a way that he often wasn’t.

Bourdain didn’t speak much about addiction or other troubles in his life. Outside of asking his family and friends about it, how did you get closer to the aspects of Bourdain’s struggles that weren’t so well documented?

I actually think if you look at his books carefully, he’s much tougher on himself. But he still had a willful blind spot. He was aware that there were things he was running away from, but he never really wanted to analyze them. He just knew this was what he wanted — to be more on the edge, more out of control. It’s all the stuff tied into addiction, and also his other mental issues. It’s not explicit in the film but it’s implied. He said at one point, “I make best friends one week at a time.” I’ve talked to people who said he would travel to a country, spend a week with them and they’d think he was their new best friend. But they’d never hear from him again.

CNN obviously had to give this project its blessing. How did you manage to tell this story on your own terms?

The good thing about working with people like Amy Entilis at CNN [who produced “Parts Unknown”] is that they all knew they were way too close to the story. But as sensitive as it was, they’re all storytellers and understood the necessity of it. I can always win on the logic. That was true for almost everybody I talked to. Tony demanded a kind of brutal honestly. People felt that they were talking to me and that they’d never do it again. Ottavia Busia [Bourdain’s widow] says exactly that in the film, but a number others did so privately. This was the time to say their piece, one time, and be done with it.

Anne Thompson

Did you establish any terms with your subjects before you interviewed them?

There were no pre-terms. There was this understanding from people. I started the interviews a year and a half after he died and did them for almost a year. Throughout all of those interviews, it was like a tour of the stages of grief: Real anger, real sadness, real forgiveness, all these things at different times. That experience was what made me feel like at the end of the film, they needed to have a say, too.

Who would you have loved to include but couldn’t?

There were a couple of people I asked to do interviews who declined. I let it go. A couple of people in the film declined. I pushed and pushed and some agreed to do it. Tony’s first wife Nancy didn’t want to talk. But my story begins at the tail-end of their marriage so by the time I started cutting the film, it didn’t feel as necessary. I interviewed another 13 or 14 people who aren’t in the film. I interviewed David Simon and Gabrielle Hamilton. Simon said great things. You have to cut out things you love.

What did Simon talk about?

The whole “Treme” story where Tony wrote a bit on “Treme.” Not only that, but he wrote the whole scene for Emeril Lagasse to deliver a speech rebutting everything Tony had ever criticized him about. I had a whole scene about that, and I loved it, but it took so long to set it up and explain it. At the end of the day, it just didn’t fit.

If you look at the speech that Emeril gives on the show — Tony always criticized Emeril for franchising himself, being a sellout, a TV character. On “Treme,” he gives this really great speech about how when you’re running a restaurant, you’re the captain of the ship and everyone is looking at you to help feed their families. At a certain point, you have to keep feeding more and more people who show up on the ship. All you know at the end of the day is that you’re trying to protect people who are helping you. It’s really what Tony had grown into. His criticism of Emeril is rooted in his young, brash days of “Kitchen Confidential.” But by the time he wrote that, he was running his own pirate ship of a TV show for a decade or more. So he got it.

You chose not to request an interview with Asia Argento even though she was a key part of Bourdain’s life at the very end. At what point did you arrive at the conclusion not to reach out to her?

Pretty deep into it. We’d been editing for a long time and part of it is that once you start getting into the revelations that came out after he died — that he was supporting lawsuits, things like that — once you start to crack the door open on that, it just becomes insanely complicated. There were so many things in their story that the moment you crack it open…believe me, early on in the editing, I started getting into more of that, and when I’d show it to people, all I would get is 10 more questions. It just made the film spiral.

I looked at everything she’d said in interviews after Tony died. I pretty much know what she’d say, which is that she loved him, and felt misrepresented by people. I also knew, honestly, that to interview her, you would incur a lot of bad blood from lots of people in Tony’s life. So there was a price to pay, too.

You mean some of your existing subjects might not have participated if you’d talked to her? The people who resented Argento after he fired them and spent more time with her?

I’d been sitting with these people for hours and days, not just on camera. At times I felt like the group shrink. There’s a certain amount of trust and vulnerability these people gave me. Nobody said there was no way I could do it, but I knew that if I was going to do it, I’d better be damned sure it’s what I wanted. When I really thought about it and talked about it at great length, I just felt like I didn’t think it would give me more insight into Tony at the end of the day. I wouldn’t have understood what he was thinking more than I already did.

Beyond the Argento factor, how did you strategize about your approach to the suicide? Early on, you tell one of your subjects that you aren’t looking to make that the focus on the movie. But it’s obviously unavoidable, and since he didn’t leave a note, will always be a mystery.

My journey in making the film is that in the beginning, my first reaction was that I found him fascinating and always have. I also felt like he was a fellow traveler, a kind of documentary filmmaker telling stories about other people and using all the tools of filmmaking to create empathy and understanding for other people. There was lots of stuff that instinctively gravitated towards. And once I committed to the film, I instantly realized I was making a film about suicide.

OK, so what did you learn?

A few things. He was somebody who kept track of suicides. He was a suicide-ologist. He had a fascination about it. Secondly, he joked about it all the time. We had a whole montage of them at one point. There are many, many examples in books and on the show of him joking about suicide. If people thought he was really going to kill himself, they wouldn’t be jokes. But in retrospect, I think a lot of people are kicking themselves for feeling like they misread the situation, which I think is an unfair burden.

Thirdly, he wrote this thing in the book “Medium Raw” — and we had a scene about it — about when he was in a radio station in Antarctica. After the breakup of his marriage to Nancy and before he met Ottavia, he was at loose ends. He was on St. Martin, this mountainous island in the Caribbean he always liked to go to. Late one night after many drinks, he was driving on the mountain road, and there’s a big turn on the cliff, and he started to drive right toward the edge of the cliff. At the last minute, The Chamber Brothers came on the radio, with “The Time Has Come Today,” and something about it made him swerve and not drive off the cliff.

Stephen Lovekin/Variety/REX/Shutterstock

In other words, the signs were there, but nobody was really looking for them.

The summation of all this is that for people who really knew him were shocked, but not really surprised. There were a number of situations where people thought, “God, he really got away with that. He was really being reckless.”

It’s one thing to assess a tragedy like this decades down the line. But Bourdain killed himself in 2018. What did you glean about the long-term potential of his legacy from working on this project so soon after his death?

There’s a story I haven’t told yet. I think it’s fair for me share. It taught me a lot about how people think about suicide. Shortly after Tony died, his estate was approached by a suicide prevention society asking to use his name. They declined because Tony would’ve hated it. A year later, they came back, and asked again. They started to decline and they stopped themselves and said, “Tony doesn’t get the say anymore. Tony advocated for what he wanted when he killed himself.” Of course that’s true and not true. People want to honor what he would’ve wanted — his words and his work — but there’s a part of his life that Tony doesn’t get to say a word about. It’s that last piece of the film, the crater he left when he killed himself.

You must be wondering what he would have made of “Roadrunner.”

I think Tony would’ve liked that I’ve done films on Iggy Pop, Keith Richards, and Orson Welles. He would’ve appreciated that part of it. I got a couple of emails from people in the film after they saw it, one of them saying that Tony would’ve been proud, and another saying “Tony would’ve begrudgingly loved this.”

“Roadrunner: A Film About Anthony Bourdain” premiered at the 2021 Tribeca Film Festival. Focus Features releases it theatrically on Friday, July 16.

Best of IndieWire

New Movies: Release Calendar for July 9, Plus Where to Watch the Latest Films

Long-Awaited Sundance Standout 'Zola' Lights Up the Specialty Box Office

Sign up for Indiewire's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.