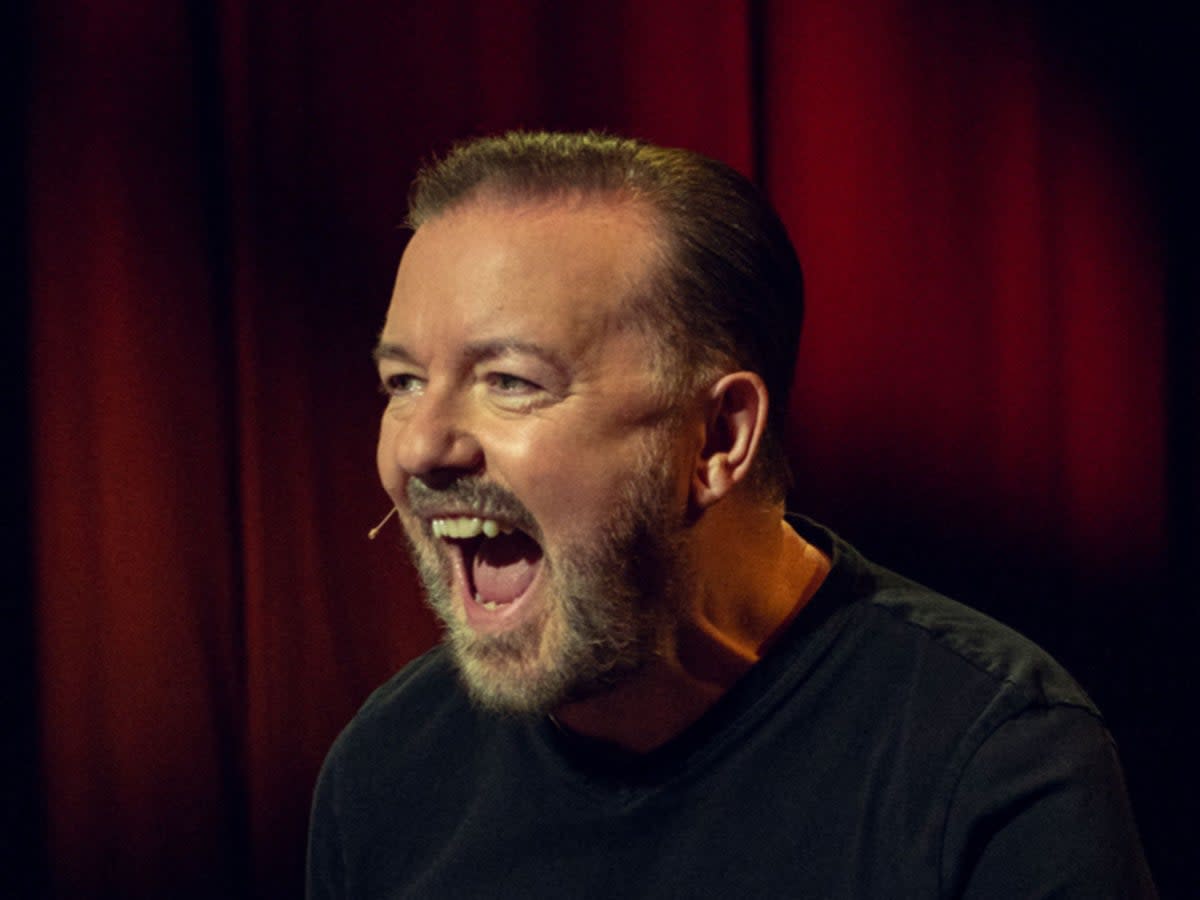

Ricky Gervais knows he won’t be cancelled by his jokes – his lazy new special is proof of that

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

You’ll realise this is great satire when I’m dead,” Ricky Gervais, purveyor of increasingly cheap comic shocks, announces, in the twilight moments of his new Netflix special, Armageddon.

He’s being ironic: even by Gervais’s own estimation, the show is not a piercing satire. In fact, it is almost an anti-satire, a list of unsayable things for which Gervais invites his audience to provide meaning. The problem is that, unlike “great satire” – which is provocative, incendiary and takes the abuses of the establishment to task – Gervais has become trapped in the web of political correctness.

Let’s play a game: find a quote by a serving Tory MP that corroborates a view expressed by Gervais in Armageddon. “I wish there were no homeless people,” says Gervais with a cheeky grin, “because they’re f****** horrible.” “We cannot allow our streets to be taken over by rows of tents occupied by people,” Suella Braverman MP tweeted, in November, “living on the streets as a lifestyle choice.” “Now,” Gervais observes, “the word ‘queer’ can mean a straight man who wants some attention,” while, on that theme, Tory MP Rachel Maclean retweeted a post that called a trans fellow politician “a man who wears a wig”. Gervais encounters an illegal immigrant, clinging to the bottom of a truck, on his way to “Gary Lineker’s house”, while Lee Anderson, deputy chair of the Conservatives, wrote in March that “instead of lecturing, Mr Lineker should stick to reading out the football scores and flogging crisps”. I could go on.

Great satire requires an attempt to lampoon the prevailing orthodoxy, not reinforce it. Gervais, and his braying audience at the London Palladium, are wholly uninterested in subverting the political establishment. “I’m going to be woke from now on,” Gervais announces, at the outset of his seventh stand-up special. But “wokeism” is hardly a dominant ideology: polling by YouGov in 2022 said that, of people who used the word “woke”, 73 per cent did so disapprovingly. Of those who understood the term, 62 per cent said it did not apply to them, versus 28 per cent who said it did. In short, it is more subversive to be woke than not to be.

Where Gervais has always been interesting – and one of the rare places he challenges conservative conformity – is on the subject of religion. His atheism is a persistent theme throughout his stand-up and sitcoms (particularly After Life, which deals with grief in the absence of spiritual consolation). He previously co-hosted a podcast, Absolutely Mental, with Sam Harris, one of the so-called Four Horsemen of “New Atheism”. But the confluence of a resurgent evangelism on the Right and the Left’s inclusivity agenda mean it’s a topic that has gone out of fashion in comedy in recent years. Precisely, then, the sort of target that Gervais revels in. And yet, for all the potential that a show called Armageddon (which, after all, is the Greek name for Tel Megiddo, a village in northern Israel) could have to deal with religious fervour, Gervais plays it safe. His barbs, when they come, are reserved for those who deny that humans are apes. Hick anti-evolutionists are easier to take on than real, militarised dogma.

What is humour for, Gervais asks, as he closes the show. “To laugh at bad s*** to get us through it,” he answers, and the audience greet this insipid, late-in-the-day moralising with a hearty round of applause. But what is that “bad s***”? The biggest chunks of Armageddon (a show that should be referred to the Advertising Standards Authority, given how little it deals with the end of the world) are reserved for jokes about disabled people (because that’s taboo, right?). Are other people’s disabilities the “bad s***”?

In one extended riff on the fragility of the modern mindset, Gervais finds a site that provides trigger warnings for difficult content and reads the entry for Schindler’s List. The audience can see where he’s going and sit with rapt attention. He reels through a list of nonsensical questions that have been asked about the film (“Are there fat jokes?” or “Are there ‘man in a dress’ jokes?”) before arriving at the one he thinks is most absurd: “Is someone misgendered?”

The joke is that people are so sensitive that they dare not watch Schindler’s List without checking for transphobic content. Thorough investigative journalist that I am, I went to this site – doesthedogdie.com – and found that question in the entry for Steven Spielberg’s Holocaust drama. It is accompanied by one note that reads: “Does the other commenter not realise that every movie and show on this site has the exact same list, no matter what?” Far from being the product of some snowflake’s easily offended sensibilities, the enquiry is just an identikit form applied to every film and TV show on the database.

But the gag is easy, because Gervais knows that the British public and its elected politicians think that there is an insurgent thread of mental infirmity among a generation of young people. That is the politically correct opinion. Gervais’s jokes, which mock illegal immigrants, homeless people, trans people and more, are the sort of opinions that, far from getting you cancelled, are likely to be vote winners at the ballot box. Rather than being “great satire”, Armageddon is just another piece of lazy comedy that plays on the majority’s fear of minority voices.